A bill in Tallahassee could save Amazon more than $1 million a year

Property-tax legislation to help everyone from Jeff Bezos to JetBlue

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the journalism of others — that examines the many ways that businesses influence public policy across Florida, written by Jason Garcia.

Amazon.com Inc., the Internet giant that turned a $33 billion profit last year, flies nearly two dozen flights a day in and out of a small airport in Lakeland, about halfway between Orlando and Tampa.

The flights are part of a $100 million air-cargo hub that Amazon has built at the publicly owned airport, which has become a key cog in a global package-delivery network that has helped make Amazon one of the world’s largest retailers.

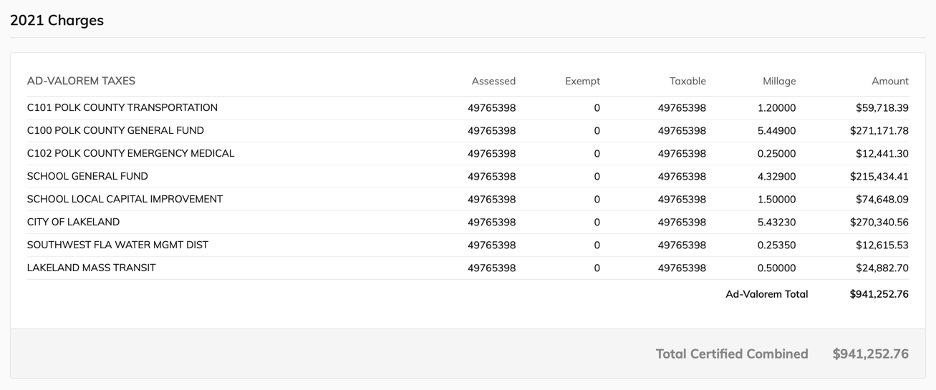

Amazon paid $941,252.76 in taxes last year on that property – about the cost of a dozen public-school teachers.

But Amazon’s annual tax bill could disappear thanks to bills moving through the Florida Legislature.

The legislation, which gets its first hearing tomorrow in the House Ways & Means Committee, seeks to help many businesses avoid paying property taxes on land they lease at airports, seaports and spaceports. It comes amid escalating conflict between private companies and local property appraisers – including a pair of pending court cases that pit the appraiser in Hillsborough County against businesses leasing land at Tampa International Airport and Port Tampa Bay.

The bills would reverberate far beyond Tampa.

There’s Amazon’s package hub in Polk County, where city officials initially told Amazon it wouldn’t owe any property taxes. But there’s also JetBlue Airways Corp., which is currently battling Orange County over whether JetBlue should pay taxes on a training center and employee hotel it runs at Orlando International Airport.

And at least two appraisers have clashed with Space Florida, a state agency that has been negotiating complex lease deals in order to eliminate the property tax bills for companies such as defense contractor Northrop Grumman Corp., airplane manufacturer Embraer S.A., Jeff Bezos rocket company Blue Origin LLC, and aviation-training firm SIMCOM Holdings Inc.

It’s not clear whether Amazon itself is lobbying for the legislation. But it has a big stake in one of the companies that is: Air Transport Services Group Inc., an Ohio-based corporation that owns a pair of subsidiaries involved in the Hillsborough County litigation. Amazon owns 20 percent of Air Transport.

Air Transport has in recent months become a modest Florida campaign contributor, too. On the day before this year’s session began, records show the company gave $1,500 to the political committee controlled by Rep. Bobby Payne, a Palatka Republican who chairs the House Ways & Means Committee.

The Legislature vs. the Constitution

What’s ultimately driving this is tension between three things: 1) A Florida Constitution that strictly limits property tax exemptions; 2) A Florida Legislature that has tried to stretch those limits as far as it can; and 3) A Florida Supreme Court that has tried to reel the Legislature back in.

For instance, the Constitution says simply that property owned and used by a city “for municipal or public purposes” is exempt from property taxes.

The Legislature has expanded this to include property that a city leases to a private entity – as long as the private entity is still using the property for a public purpose.

The Legislature has also defined “public purpose” very broadly. The current definition includes convention centers and concert halls, sports stadiums and spaceports, and virtually any aviation- or maritime-related operation at an airport or a deepwater seaport. (Business lobbyists, economic-development dealmakers, and local elected officials who love job-creation announcements and ribbon-cutting ceremonies then take these broad definitions and run with them.)

But Florida courts have repeatedly ruled that exemptions for companies leasing government land can only be stretched so far.

The most well-known example involves the “12 Hours of Sebring,” a world-famous endurance grand prix race run every year at Sebring Regional Airport in Highlands County.

In a nutshell, a private company took over the race in the early 1990s, leasing the land from the airport. It applied for a tax exemption but was denied by the local appraiser. The Supreme Court ultimately sided with the appraiser, ruling, essentially, that a company engaged in a purely profit-making enterprise wasn’t eligible for a tax exemption simply because it leased land from the government.

Race supporters then lobbied the Legislature to overturn the decision by explicitly adding sports stadiums to that definition of public purpose. The whole process repeated itself, and the Supreme Court again denied the exemption, ruling that “mere labeling” by the Legislature didn’t change whether something was truly a public purpose.

Taking sides

That’s about where we are today. In the context of an airport, the Legislature says that basically anything related to aviation qualifies for an exemption. But the courts say only activities that fulfill a true public purpose are in; activities that are purely for profit are out.

There’s general consensus at the extremes: A passenger airline leasing gates at an airport is exempt but a hotel leasing land at an airport is not.

But there’s a big mushy middle in between. What about a company using airport property to build private jets that cost $30 million a pop? Or to train its own pilots or mechanics? Or – like Amazon – to sort and ship its own packages?

The cases out of Tampa, which are currently awaiting decisions from the Second District Court of Appeal, could resolve some of these questions once and for all. That’s what has so many people worked up – and why this issue is back on the legislative agenda in Tallahassee.

The bills (HB 1387 in the House, SB 1840 in the Senate) wouldn’t directly affect the court cases. But they do try to reinforce the legal arguments being made by the companies that want the exemptions.

Perhaps more importantly, they also strengthen the hands of other companies that try to seek these kinds of tax exemptions in the future.

This is especially true of the Senate bill, which is sponsored by Sen. Joe Gruters, the state lawmaker who doubles as chairman of the Republican Party of Florida.

Right now, if a property appraiser denies someone a tax exemption, they can appeal to the local “Value Adjustment Board,” a panel comprised of two county commissioners, a school board member, and two political appointees. If the VAB sides with the property appraiser, the taxpayer can appeal in court; if the VAB sides with the taxpayer, the property appraiser can appeal in court.

Under Gruters’ bill, the property appraiser would be forbidden from appealing. The VAB’s decision would be final – as long as the VAB sides with the taxpayer seeking the exemption.

This provision would have snuffed out both the Tampa court cases before they ever began. It’s also a potentially powerful tool for a company like Amazon, which has yet to try applying for an exemption on its land at the Lakeland airport.

There’s no doubt the company has thought about it. Amazon’s original lease with the city included a provision in which the city pledged to Amazon that its holdings wouldn’t be subject to property taxes. (That fell apart when the local property appraiser, a Republican, and her attorneys concluded that Amazon would, in fact, have to pay property taxes.)

And the stakes for Amazon will only continue to grow. The company is already working on an expansion at the airport that would add another 65,000-square-foot sorting facility and a 370-slot truck bay – which would push its property tax bill well beyond $1 million a year.