A developer-backed bill would make it easier to convert low-income housing into high-priced apartments

'In Florida, they’re not happy with the loophole as wide as it is – they want to widen it'

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the journalism of others — that examines the many ways that businesses influence public policy across Florida, written by Jason Garcia.

Amid a statewide affordable housing crisis, a pair of big developers are lobbying the Florida Legislature to make it easier to convert publicly subsidized apartments meant for low-income tenants into high-priced, market-rate rentals and condos.

The measure, which was quietly attached last week to an otherwise benign bill in the Florida Senate, has alarmed advocates, who warn that it could lead to the loss of as many as 40,000 low-income apartments across a state that already has a dire shortage of affordable housing.

The controversy is tied to a decades-old provision in the federal law that governs the national affordable-housing program, which advocates say has become a loophole that developers are exploiting to escape restrictions on the amount of rent they can charge.

“In Florida, they’re not happy with the loophole as wide as it is – they want to widen it,” said Robert Rozen, a former staff attorney in the U.S. Senate who helped write that federal law.

The developers lobbying for the Florida legislation include Jacksonville-based Vestcor and Winter Park-based Atlantic Housing Partners, according to records and interviews. Both are major campaign contributors.

In the month before this year’s legislative session, records show that John Rood, the chairman of Vestcor, gave $100,000 to a political committee controlled by Sente President Wilton Simpson, a Republican from Pasco County. Rood also gave $50,000 to a committee controlled by Sen. Kathleen Passidomo, a Naples Republican who is the second-highest ranking senator, and $53,000 to Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who will ultimately have to sign off on any legislation before it can become law.

The same month, an entity affiliated with Atlantic Housing gave $25,000 to Simpson, who is raising money to finance a campaign for Florida commissioner of agriculture.

A loophole that opened over time

Under the nation’s Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program, the federal government gives tax credits to developers that commit to keeping rents affordable for low-income tenants for at least 30 years. States, which administer the housing program and provide additional incentives, can demand even longer affordability periods. Florida requires up to 50 years.

But there is an escape hatch.

When an affordable housing development is approaching its 15th year, the owner – who is usually the original developer – can inform the state that it wants to sell the property. That triggers something known as the “qualified contract” process, under which the state has one year to find a buyer willing to purchase the property at a price set by a formula in federal law.

If the state finds a buyer willing to offer a qualified contract, the owner of the development can decide to sell the property or take it off the market. But either way, the development will remain bound by the affordability restrictions for the rest of the tax-credit agreement – another 15 to 35 years.

But if the state can’t find a buyer willing to offer a qualified contract, the affordability restrictions are removed. After a short transition period, the owner is free to convert the development into higher-priced market-rate apartments or to sell units off as condos, both of which are far more profitable than rent-restricted low-income housing.

The qualified contract process was created in 1989, when the still-new federal housing program went from requiring developers to make 15-year commitments to mandating 30-year commitments. It was designed to entice investors who might be wary of putting up money for a development bound by long-term rent controls, by guaranteeing them a minimum return on investment.

The problem is that the formula that determines the asking price, which was set more than three decades ago, is leading to prices today that are typically far higher than what buyers are willing to pay for a rent-restricted housing development. Advocates say that developers are using the qualified contract process knowing the state won’t be able to find a buyer – and then they’ll able to start charging much higher rents.

Nationwide, the country is now prematurely losing more than 10,000 low-income apartments a year to the qualified-contract process, according to the National Council of State Housing Agencies.

“People are using a statutory formula – designed to prevent backend windfalls to owners and investors by limiting them to an inflation-adjusted return on their original equity contribution – almost like an opt-out, which was not the intent,” said Scott Hoekman, an executive at Enterprise Community Partners, a national nonprofit that helps finance affordable housing projects.

Giving developers veto power

This problem isn’t quite as severe in Florida, where real-estate prices are rising so rapidly that the state has had more luck finding buyers willing to pay the qualified contract price.

According to the Florida Housing Finance Corp., the agency that administers the low-income housing tax credit tax program, the owners of 90 affordable housing developments have triggered the qualified contract process in Florida to date.

The agency was unable to find a buyer for 56 of those developments, which led to the loss of nearly 12,000 units from the state’s affordable housing inventory. But it has found enough buyers to keep the remaining 24 developments in the program, preserving more than 6,000 affordable units.

That’s where the new legislation (SB 196) comes in. It would set stricter conditions on the terms required for a qualified contract.

Right now, in order to ensure a development remains affordable, the state housing agency must present the owner with a contract offer at the minimum price that has been signed by the buyer.

Under the new language, the requirement would change to a “commercially reasonable” contract that has been signed by both the buyer and the seller.

In other words, the owner of the development could make sure they do not receive a qualified contract simply by refusing to sign.

Advocates say that’s an enormous problem because most owners don’t actually want to sell – they just want to ditch the affordability restrictions.

Data from Florida’s housing agency show that when owners trigger the qualified contract process and the state finds them an offer, they almost always turn it down.

Lobbyists for the developers say the current process has been hijacked by bad-faith buyers who are using the qualified contract process – and the threat that a project will have to stay locked into its affordability commitments – as leverage in other real-estate negotiations.

In recent litigation against Florida’s housing agency, affiliates of Atlantic Housing accused the agency of providing qualified offers submitted by a buyer who had no intention of actually following through with them. The proposed contracts were riddled with errors, like misspelled names and missing legal descriptions, and the buyers “seemed more interested in obtaining better below-market prices for other developments,” lawyers for Atlantic Housing affiliates wrote in a court filing.

The Atlantic affiliates and the housing agency opted to settle. But lobbyists say the new legislation is in response to abuses like that. The goal is to ensure legitimate offers.

But the language they’re lobbying for goes a lot further than that.

“What this Florida amendment is trying to do is basically make sure that no qualified contract is ever actually offered, so that it will always result in getting out of the affordability restrictions,” Hoekman said. “It’s taking a process that really needs to be repaired and making the problem that much worse.”

There are other issues, too.

Nationally, housing advocates have been lobbying Congress to end the qualified contract process entirely for future developments – and to rewrite the sale-price formula for existing developments. Both ideas were included in President Joe Biden’s “Build Back Better” spending package, which has so far failed to get through Congress.

The legislation in Tallahassee includes a provision that could amount to an end-around to any future federal changes. It could ensure that any existing developments in Florida that try to use the qualified contract process still fall under that 1989 formula – boosting the odds that no offer will come through and they’ll get to go market-rate.

It's worth noting that Florida already treats affordable housing developers more gently than it could. Some states have banned qualified contract outs entirely. Florida has instead opted to incentivize developers to waive the right when they apply for tax credits – which only works in programs for which applicants must compete for a finite amount of funding.

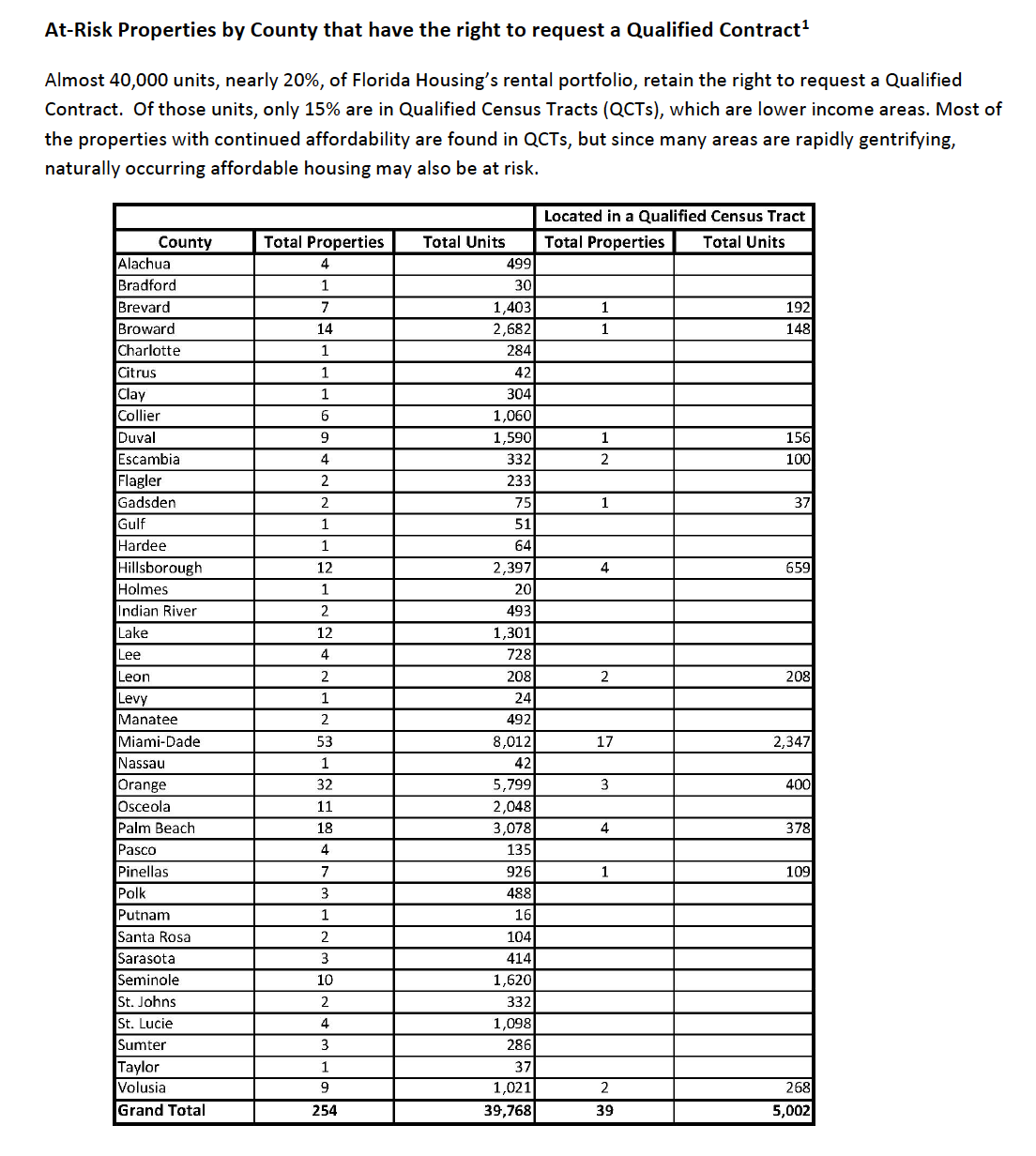

Altogether, Florida’s housing agency says more than 260 affordable housing developments – with nearly 40,000 in combined units – currently have the right to use the qualified contract process. That’s about 20 percent of the agency’s total stock of affordable housing.

What’s especially galling to some is that this provision was added onto a pro-housing piece of legislation that otherwise had widespread, bipartisan support: a bill that would speed up the process for selling bonds needed to build more affordable housing.

“This amendment does the opposite of what the bill is supposed to do,” said Sen. Annette Taddeo, a Democrat from Miami.

The amendment was added during the Feb. 2 meeting of the Senate’s Transportation, Tourism & Economic Development Appropriations Subcommittee. The sponsor, Miami Republican Sen. Ana Maria Rodriguez, initially characterized the amendment as merely a “clarification” issue – but then proved unable to explain it upon questioning from some skeptical Democratic senators, including Taddeo.

When a staffer from Florida’s housing agency was called up to help, he told the committee he wasn’t sure what the changes would do, either. And nobody else volunteered to explain it, even though lobbyists for at least one of the developers pushing for the changes were sitting in the audience and watching.

The newly amended bill then squeaked through the committee on a 6-4 vote. None of the six Republican senators who voted for it asked a single question or said single word in debate.

Contact: Garcia.JasonR@gmail.com