Candidates in Orlando split over new rules to save rural land from suburban sprawl

A proposal to make it harder for developers to build on rural land has become a bright dividing line in three key races for seats on the Orange County Commission.

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter and podcast devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the work of others — about Florida politics, with an emphasis on the ways that big businesses and other special interests influence public policy in the state. Seeking Rents is written by veteran investigative journalist Jason Garcia, and it is free to all. But please consider a voluntary paid subscription, if you can afford one, to help support our work.

When voters in Orlando go to the polls this fall, they will find suburban sprawl on the ballot.

It’ll be there in the form of two referendums that would establish new protections for rural lands in Orange County, the rapidly growing region of nearly 1.5 million people that includes the city of Orlando.

But it will also be on the ballot in the form of three county commission races, where rural land protections have also become a bright dividing line between the candidates.

The divide centers on one of the two referendums, which together aim to create a strong “rural boundary” in Orange County. The measure would make it much harder for a developer to dodge new rural development limits simply by convincing some growth-hungry city to annex the land — something that cities like Orlando are often happy to do, even when it means swallowing up a vast swath of cattle pasture that is closer to the St. Johns River than it is to City Hall.

On one side are a trio of candidates who all say they support the proposed limits on municipal annexation power: Nicole Wilson, the incumbent commissioner in District 1, which covers western Orange County; Mayra Uribe, the incumbent commissioner in District 3, which takes in parts of south and east Orlando; and Kelly Semrad, a university professor running for an open seat in District 5, which spans the county’s eastern side.

The three have records to back it up. Wilson and Uribe both voted to place the measure on the November ballot and both say they will personally vote for it, too. And Semrad, a leader of the activist group Save Orange County, was one of the very first supporters of the idea.

On the other side are Austin Arthur, a marketing executive challenging Wilson in District 1; Linda Stewart, a state legislator challenging Uribe in District 3; and Steve Leary, a former Winter Park mayor squaring off with Semrad in District 5.

Arthur says he opposes the annexation measure. Stewart and Leary say they have not yet made up their minds about it.

But Arthur has also raised thousands of dollars from some of the key developers trying to stop the referendum. So has Leary. And Stewart voted in favor of a developer-backed bill in Tallahassee that was meant to block it from the ballot in the first place.

The differences here are important.

Not because of the referendum itself, which will be decided directly by Orange County voters. But because they offer a window into how these candidates are likely to vote as commissioners when they are inevitably asked to sign off on some new subdivision in a remote corner of the county — which are often among the most consequential votes commissioners ever cast.

It also mirrors a similar divide between the candidates on tourism policy — and whether Orange County leaders should fight for the right to spend local hotel taxes on projects and services that support local residents, like police, housing and transit.

Wilson, Uribe and Semrad all say they unequivocally support using hotel taxes for local needs.

Arthur, Stewart and Leary are again more circumspect — and each has also been endorsed by the tourism industry’s main lobbying group in Orlando, which pushes local politicians to spend virtually all hotel taxes on subsidies for tourism and sports businesses.

We took a deep dive into how these six candidates line up on tourism taxes last week. Now, let’s take a closer look on where they land on suburban sprawl.

A long-fought battle, from Orlando to Tallahassee and back

This is all part of what has become a more than year-long battle to establish a rural boundary in Orange County — a battle that has already drawn in everyone from neighborhood activists to the Mormon Church to Gov. Ron DeSantis.

It began last July, when Semrad, the university professor running for the District 5 county commission seat, submitted a rural boundary proposal to an obscure organization called the “Orange County Charter Review Commission.”

That’s a group of local residents, appointed by Orange County’s mayor and commissioners, that convenes every four years to consider changes to the county charter — essentially a county-level constitution. The commission has the power to put proposed amendments directly onto the ballot for Orange County voters, who must approve any changes in a countywide referendum.

The commission spent the next few months quietly studying the measure, which was modeled after a similar rural boundary in neighboring Seminole County. Then, in February, it became clear that the commission was likely going to put the idea to voters.

The real-estate lobby lurched into action to stop it. One developer — McKinnon Groves., which is run in part by a former Orange County commissioner and local Republican donor — hired a lobbyist who warned the charter review commission to back down.

At the same time, a larger organization — the Association of Florida Community Developers — lobbied state lawmakers in Tallahassee to step in. The association’s leading members include the influential Orlando developer Tavistock Development Co. and a Mormon Church-owned real-estate company that are jointly developing an enormous expanse of ranchlands in east Orange County.

The lobbying blitz worked — sort of. Florida’s Republican-controlled Legislature slipped a last-minute provision into a bill dealing with the state’s Department of Commerce that stopped the Orange County Charter Review Commission from putting a rural boundary amendment onto the ballot. DeSantis then signed the bill into law.

But activists then turned to the county commission, which also has the power to suggest changes to the county charter. And this summer, the commission voted to put the rural boundary on the November ballot — splitting the proposal into a pair of separate-but-related referendums.

Developers are still trying to kill it. Last month, a company trying to build an 1,800-acre subdivision in rural east Orange County — a project called “Sustanee” that county commissioners rejected earlier this year on a 4-3 vote — sued to stop the referendums.

That case has yet to be resolved.

What the amendments do — and where the candidates stand

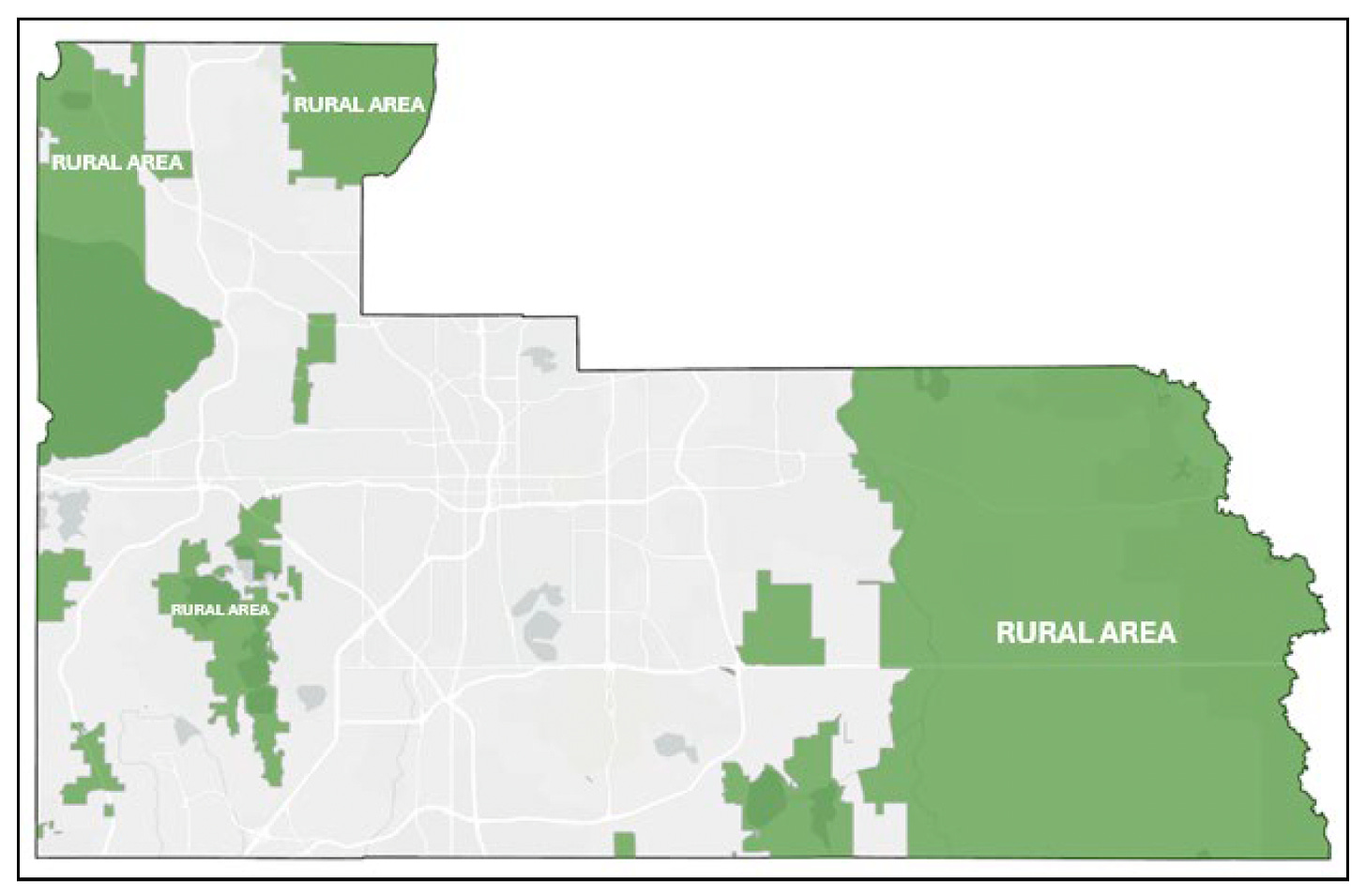

The first of the two amendments would establish the rural boundary — zones of largely undeveloped land, mostly along the far eastern and western edges of Orange County. The amendment would also require any developer that wants to build a higher-density subdivision on land within that rural boundary to get approval from a supermajority of the county commission, rather than just a simple majority.

That first amendment has widespread support. All six candidates running in Orange County’s three commission races — Nicole Wilson and Austin Arthur in District 1; Mayra Uribe and Linda Stewart in District 3; and Kelly Semrad and Steve Leary in District 5 — say they will vote for it.

But there’s an obvious escape hatch here. Even if voters approve the rural boundary, a developer looking to build within it could get out from under the new rules just by persuading a city to annex the land.

That’s where the second amendment comes in. It would require a supermajority of county commissioners to approve annexations, too. That would give Orange County veto power over any attempt to remove land from the rural boundary.

That second amendment is the one that splits the county commission candidates.

District 1

In District 1, for instance, Wilson said the annexation amendment is critical to closing what would otherwise be a gaping loophole in the rural boundary.

“One of the things that became abundantly clear to me really early on in my tenure, was that [annexation] was being utilized as a way to circumvent our Environmental Protection Division regulatory scheme,” Wilson said in August, when she voted to put the amendment on the ballot.

But Arthur said he opposes the annexation amendment — at least partly because he believes that, even if voters approve it, the amendment will ultimately be overturned by a court or the Florida Legislature.

Arthur likened it to previous efforts in Orange County to pass a so-called “rights of nature” environmental-protection law and to freeze residential rents for one year. Both proposals passed with overwhelming support from Orange County voters but were blocked by Republican lawmakers in Tallahassee.

“Like many amendments pushed by Nicole Wilson — such as the Rights to Clean Water and rent control — this will result in burdening taxpayers with costly litigation and will be overturned,” Arthur said. “We need a commissioner who can work within legal frameworks, collaborate with stakeholders, and create sustainable solutions that truly benefit our residents without exposing the county to unnecessary legal risks and financial burdens.”

It’s revealing that Arthur seems to think the villains in those previous battles were the activists fighting for changes like stronger environmental laws and rent stabilization — rather than the Tallahassee politicians and corporate interests who conspired to stop them.

But many of those same interests are supporting Arthur’s campaign. To cite one relevant example: Campaign-finance records show that companies connected to McKinnon Groves — the developer that hired a lobbyist to oppose the rural boundary plan — have bundled at least $5,000 to Arthur so far.

District 3

Meanwhile, in District 3, only one of the candidates is open about where she stands on the issue.

Seeking Rents asked both candidates whether they will vote for the annexation amendment. Uribe said yes. Stewart wouldn’t say.

“Due to the legal challenges to this ballot language, I am not making a decision at the moment,” Stewart said.

Then again, in one sense, Stewart has already voted against the rural boundary plan altogether. She did so as a state senator in Tallahassee, when she voted for the developer-backed bill attempting to keep it from the ballot.

Incidentally, Stewart wasn’t alone. Most of Orange County’s other state senators also voted for that bill, including Democratic Sen. Victor Torres of Orlando and Republican Sens. Dennis Baxley of Ocala and Jason Brodeur of Sanford. Only Sen. Geraldine Thompson (D-Orlando) voted against the legislation.

District 5

Finally, over in District 5, Semrad is probably the staunchest supporter of the rural boundary generally — and the annexation amendment specifically — of any candidate on the ballot.

She’s the one who’s been pushing the whole package since last summer. She calls the annexation amendment “the teeth” that would would give bite to the rural boundary.

“Any candidate that does not support the annexation charter amendment does not support the boundary,” Semrad said.

Like Stewart in District 3, Leary says he hasn’t made up his mind on the annexation amendment yet. “As a resident and former local mayor who is a strong proponent of home rule, I am still considering how I will vote,” Leary said.

But like Austin in District 1, Leary has also taken a lot of money from developers trying to block the rural boundary.

For instance, records show that a fundraising committee Leary set up — called “Neighbors for a Sensible Orange County” — took $2,500 in July from a company run by the developer of Sustanee. That’s the same developer currently suing to get both rural boundary-related amendments thrown off the ballot.

A few weeks later, Leary’s committee took another $2,500 from a company affiliated with Tavistock — the developer whose lobbying association helped write the bill in the Florida Legislature attempting to block the rural boundary.

We MUST find an economy that doesn't depend on destroying the environment. Here is one suggestion - the billionaires pay their "fair share" and we have a guaranteed monthly income. That's not a radical idea

We all live on this planet - it amazes me that a small group can gain so much control to destroy it and gaslight it as "progress & improvement ".

Can we eat that cash from the "improvements" on the land?

Fact is - that wealthy areas usually love green spaces.