Florida has a chance to close corporate tax loopholes

An important vote looms tomorrow in the Florida House of Representatives.

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the journalism of others — that examines the many ways that businesses influence public policy across Florida, written by Jason Garcia.

One the country’s largest makers of air-conditioning systems and water heaters, Rheem Manufacturing Co. sells a lot of stuff in Florida. You’ve probably seen the company’s bright-red logo before – on the side of a condenser next to someone’s home or on the hood of a NASCAR race car.

But when it comes time to pay corporate taxes in Florida, Rheem is – at least on paper – two separate companies.

There’s the parent company, Rheem Manufacturing, which owns the rights to that logo. Then there’s a subsidiary, Rheem Sales, which actually sells the company’s products. Rheem Manufacturing forces Rheem Sales to pay licensing fees to use the company logo.

In the real world, this sort of internal shuffling is financially meaningless. Rheem is simply passing money from the left hand to the right.

But it makes a big difference in Florida, which allows corporations to use an antiquated tax system that pretends as if these were two independent companies.

So Rheem Sales files a tax return in Florida – but its tax bill is lower because it deducts all the payments it makes to its parent company. And Rheem Manufacturing does not file a tax return in Florida – so it doesn’t pay any tax on all the money it pulls out of its subsidiary.

Rheem used this profit-shifting to avoid nearly $1 million in Florida corporate taxes between 2015 and 2017, according to state auditors. They are now trying to make Rheem pay those taxes back; Rheem says it doesn’t owe a dime and is fighting the assessment.

Rheem is just the tip of a far larger tax-avoidance iceberg. Big corporations across the economy use similar accounting strategies to avoid hundreds of millions of dollars in Florida taxes. They include Aaron’s, Amazon, Best Buy, Cardinal Health, Chevron, Circle K, Dr. Pepper, eBay, Fiserv, Home Depot, Kraft, Microsoft, R.J. Reynolds, Rockwell Automation, Sanofi Pasteur, Target, UnitedHealth and UPS – the list goes on and on.

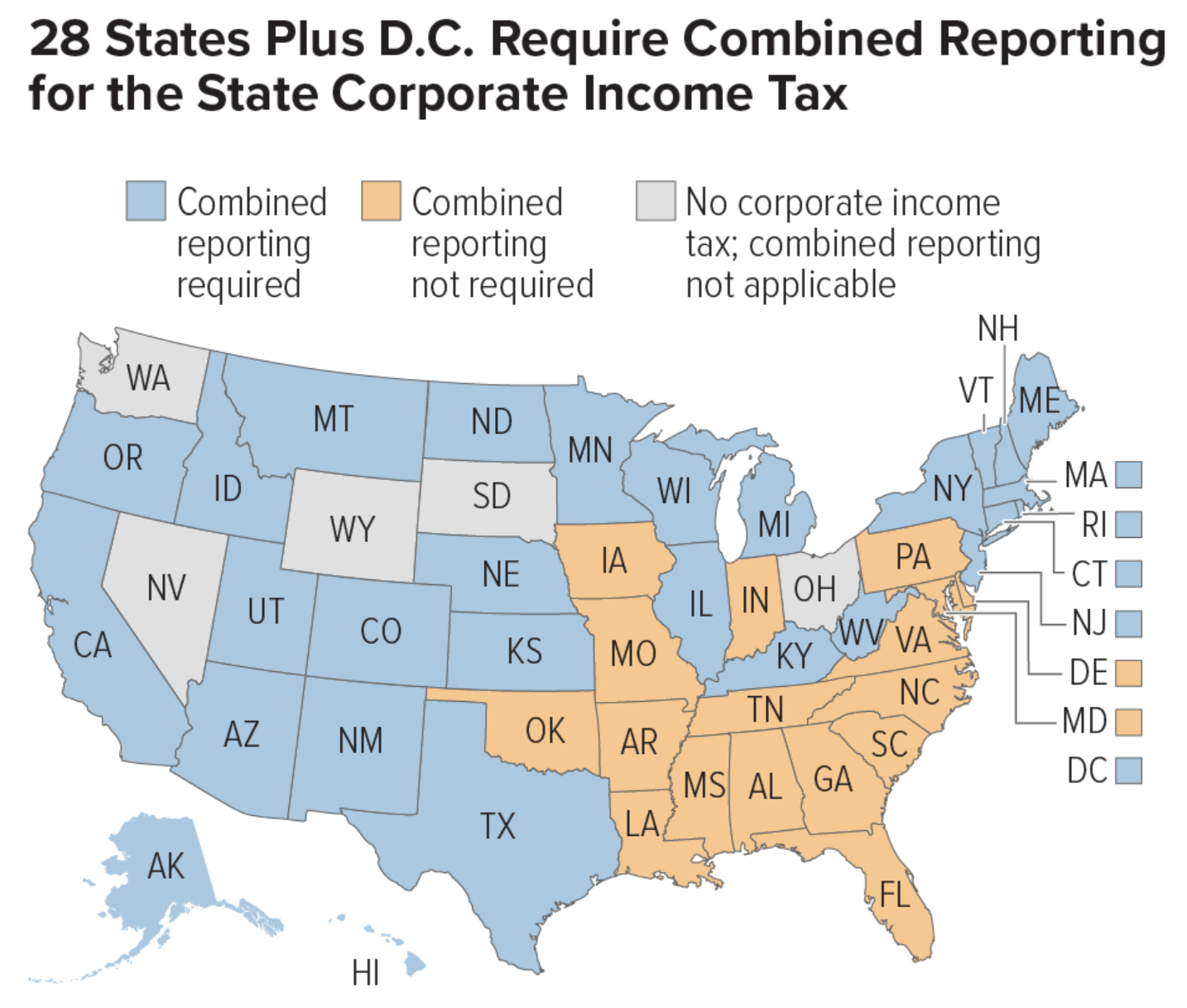

Most other states have clamped down on this kind of corporate tax avoidance by enacting a policy called “combined reporting.” It’s a technical name but a simple solution: It forces big corporations to file a single, unified tax return like the single, unified corporations they actually are, rather than letting them pretend to be a bunch of smaller companies just for tax purposes.

Florida has a chance to put a stop to this, too. On Tuesday, the state House of Representatives is expected to vote on legislation that would require combined reporting in Florida. It’s been filed by Rep. Angie Nixon, a Democrat from Jacksonville, as an amendment to HB 7071, which is otherwise a massive package of tax breaks.

It might not get much attention, but this is one of the most important decisions the Legislature will make this year. Combined reporting could generate nearly $500 million a year in revenue – all from the big, multistate and multinational corporations who have the teams of lawyers and accountants needed to game Florida’s current system. That’s more than the state of Florida currently spends on pre-school.

Why is this so important? Because the money to run a state as big as Florida has to come from somewhere.

Remember when Gov. Ron DeSantis and the Legislature stepped in to save Florida businesses from big unemployment tax increases following the COVID19 pandemic? They paid for that by forcing Floridians to pay more taxes when they buy things online.

Or remember when they celebrated new funding for projects cleaning up polluted waters and protecting coastlines against rising seas? They paid for that by cutting spending on affordable housing.

This week, the state of Florida will begin charging tolls to drive on some lanes on Interstate 4 – a highway that had, for 60 years, been completely free to all.

These issues are all connected.

How to game the system

The tactic Rheem is using – paying itself to use its own name – is one way corporations exploit Florida’s current system of separate tax reporting. But there are many others.

Take Target Corp., the Minnesota-based retailer with more than 125 stores across Florida and nearly $100 billion in annual sales.

Target earns almost all of its income selling merchandise in stores. But internally, the company makes the entity that operates those stores pay other Target subsidiaries to provide various services.

This is a key distinction. That’s because Florida has different corporate tax rules for income earned from selling merchandise versus income earned from selling services. And it’s a lot easier to game the rules for services.

One of Target’s biggest subsidiaries is called “Target Enterprise Inc.” It charges Target stores for a wide range of services – market research, merchandise display, advertising and more.

Target Enterprise files its own tax return in Florida, as if it were an independent consulting company. And it uses Florida’s easy-to-exploit tax rules to claim that none of the income it earns selling services to Target stores is taxable in Florida.

Auditors say Target used this strategy to avoid more than $15 million in Florida taxes between 2014 and 2019. Target has sued to overturn the assessments.

Some companies squeeze out even bigger savings.

For example, home-improvement giant The Home Depot Inc. operates its Florida stores through a subsidiary called “Home Depot USA Inc.” But the company makes Home Depot USA pay billions of dollars a year to another subsidiary, called “Home Depot Store Support LLC,” for services such as procurement, marketing, risk management and IT support.

In 2016 alone, Home Depot USA paid $5.68 billion in services fees to Home Depot Store Support, according to a letter protesting an audit that Home Depot wrote to the Florida Department of Revenue in June 2021.

Both Home Depot subsidiaries file separate tax returns in Florida. State auditors say the company used the transfer payments between the subsidiaries to help Home Depot avoid more than $24 million in state taxes between 2016 and 2018.

Home Depot is protesting the assessments. A company spokeswoman noted that the company is one of the biggest corporate taxpayers in the country; Home Depot says it paid 1 percent of the total net corporate taxes collected by the U.S. government in 2020.

Combined reporting makes tax-dodging more difficult

To be clear, combined reporting would not end this kind of tax avoidance altogether. But it would stop a lot of it.

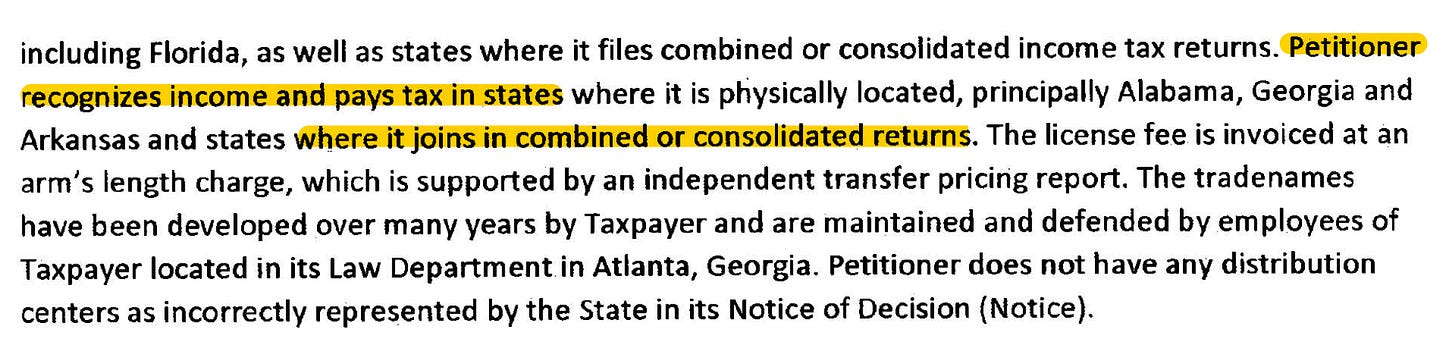

In a letter to the Florida Department of Revenue, Rheem even acknowledged that it pays taxes on the fees it charges its subsidiaries “in states where it joins in combined or consolidated returns.”

This is why big corporations have fought so hard to stop the Florida Legislature from passing combined reporting.

Through front groups like the Florida Chamber of Commerce and Florida TaxWatch, corporations and their allies throw up a thicket of often-disingenuous objections.

For instance, they call combined reporting complicated and burdensome, and say it would impose excessive compliance costs. They never mention that they’re already complying with combined reporting in most other states.

State Rep. Mike Caruso, a Republican from Palm Beach County, once claimed that IBM left Boca Raton because the state briefly enacted combined reporting way back in 1984. But IBM continued to grow in Florida after that. It didn’t leave the state until several years later – as part of a nationwide restructuring in which the company cut jobs in other states, too.

State Sen. Joe Gruters, a Republican from Sarasota County, once suggested that General Electric Co. moved its headquarters out of Connecticut because the state enacted combined reporting – even though GE moved to Massachusetts, another combined-reporting state.

And the head of the Florida Chamber of Commerce once wrote a histrionic editorial about combined reporting invoking the “socialism” boogeyman.

But the most frequent talking point, at least in recent years, is that combined reporting is not a revenue “panacea,” and that it could actually lead to lower corporate tax collections in some years.

There’s a kernel of truth to that; there are scenarios where an individual corporation might pay less tax in a given year under combined reporting. But those circumstances are rare. And there is widespread agreement among tax policy experts – including corporate tax attorneys – that combined reporting ultimately forces corporations pay taxes on more of their profits.

We’ve got a real-world case study to prove this.

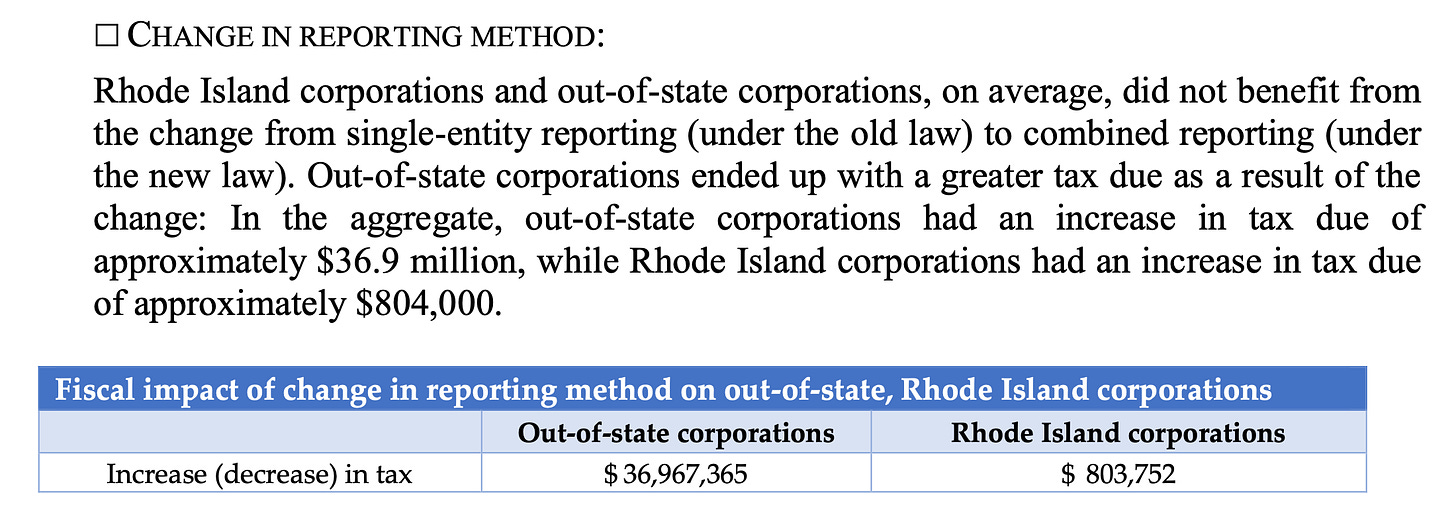

A few years ago, the state of Rhode Island overhauled its corporate tax system — enacting combined reporting but also cutting its corporate tax rate, among other changes. As part of that overhaul, Rhode Island lawmakers also instructed the state revenue department to go back a few years later to analyze the impact of all the changes.

In a report issued in 2018, the Rhode Island Department of Revenue estimated that combined reporting increased corporate tax collections by roughly 40 percent.

What’s more, the study estimated that 98 percent of that extra money came from out-of-state corporations.