Jason Brodeur pocketed $60,000 from a public grant. It’s not clear what he did for the money.

As the Orlando state senator fights to hang on to his job amid a still-growing election scandal, new records are emerging about his role in a much older controversy from a remote corner of Florida.

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter and podcast devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the journalism of others — that examines the many ways that businesses influence public policy across Florida, written by Jason Garcia. Seeking Rents is free to all. But please consider a voluntary paid subscription, if you can afford it, to help support our work.

Republican state Sen. Jason Brodeur is trying to hang on to his job as the president of the Seminole County Chamber of Commerce — and his seat in the Florida Senate — amid a still-growing scandal surrounding his 2020 election.

But 100 miles away, details are emerging about Brodeur’s role in a much older controversy: An economic-development deal in which a company co-founded by Brodeur and another state lawmaker took a multimillion-dollar grant from one of the poorest counties in Florida — a company that didn’t even exist at the time they applied for the grant and eventually went out of business.

This was one of the most controversial economic-development deals in recent Florida history. The deal was ridden with conflicts-of-interest and allegations of political favoritism, and it sparked at least two criminal investigations (but no charges), a damning grand jury report, critical audits, and years of litigation.

It unfolded a decade ago in tiny Hardee County, a rural community where the biggest employer is an industrial strip-miner. But more records are continuing to trickle out today, thanks to a public-records lawsuit that is still being fought many years later.

Much of furor over the years has focused on another politician, who, like Brodeur, was serving in the state House of Representatives at the time: Jamie Grant, a Republican from Tampa who served as the CEO of the new company — and who, according to the Tampa Bay Times, ultimately earned at least $270,000 from the venture before it failed.

But documents unearthed during the public-records litigation have revealed more about Brodeur’s role in the controversial deal, too. They include emails showing that Brodeur was included in grant application and contract discussions; bank statements and canceled checks showing that he personally pocketed about $60,000; and depositions and auditor reports that show some local officials weren’t sure what Brodeur actually did to earn that money.

Brodeur declined to discuss his role in the deal.

The Hardee County grant scandal

The Hardee County grant scandal has garnered lots of attention over the years in Tampa, the area that Jamie Grant used to represent in the Florida Legislature. The story was broken in 2013 by former WTSP investigative reporter Mike Deeson, and he stayed on top of it for years. The story was also covered extensively by the Tampa Bay Times and local news outlets.

But the scandal created barely a ripple in Orlando — the area that Brodeur still represents as a state senator from Seminole County.

It’s a long and complicated story. But here’s a (relatively) short summary:

In the fall of 2011, an agency known as the Hardee County Industrial Development Authority, which had come into millions of dollars in new money as the result of a development deal with phosphate-mining giant Mosaic, awarded the first of what became $7.25 million in public grants to a start-up company founded by Grant, Brodeur and a few other partners.

Their company — which they called “LifeSync Technologies” — didn’t yet exist when they applied for the grant. But the founders said they were going to develop online healthcare software that patients could use to manage their medical and insurance records in one place, and that their new company would anchor a technology park in Hardee County.

LifeSync fell far short of its goals. And critics claimed the entire grant process had been rigged from the start.

Among their complaints: Records show that Grant and Brodeur’s new company had a side deal in which LifeSync was going to give an ownership stake to a second company that was going to market LifeSync’s products and recruit more investors.

That second company was called Heartland Technologies. It was co-owned by another of Grant and Brodeur’s friends in the Florida House of Representatives: then-state Rep. Ben Albritton, a Republican from Hardee County.

Albritton was also the brother of a board member at the Hardee County Industrial Development Authority — the agency that gave Grant and Brodeur’s company millions in public money. (The two companies ended up not following through with the deal, and Albritton never joined Grant and Brodeur as a co-owner of LifeSync.)

The controversy set off at least two criminal investigations, one by the local state attorney and another by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. No charges were filed, but a grand jury issued a scathing report that chastised many of the people involved — including Brodeur and Grant, who, the grand jury said, had helped make a “pied piper” presentation that local economic development officials gullibly followed.

Meanwhile, an independent review by the state Auditor General blasted the local officials who had approved the deal for failing to sufficiently scrutinize LifeSync’s finances, and for failing to adequately monitor the company’s performance. A later follow-up report by the Auditor General reaffirmed the findings.

The company itself wasn’t a total failure. A later incarnation of the business — after it had been essentially bought by one of Grant and Brodeur’s partners and renamed “CareSync” — eventually grew to nearly 300 employees, split between offices in Tampa and Wauchula, a small city in Hardee County.

But CareSync abruptly shut down in mid-2018 and laid off all its workers.

Grant told the Tampa Bay Times that the company failed because of a “hostile takeover.” Another company owner told the newspaper that CareSync ultimately spent more than $13 million employing people in Hardee County. And the head of the Hardee County Industrial Development Authority — who had helped broker the original grant deal — told the Times that he was satisfied with the results and wouldn’t try to get any of the grant money back.

Litigation reveals more records

That could have been the end the story — except for the public-records lawsuit that continues to grind on today.

Filed by a Hardee County resident and longtime critic of the LifeSync deal, the suit accuses local economic development officials of concealing public-records that should have been turned over years ago.

The litigation has revealed many details — such as the involvement, at least tangentially, of a fourth Republican state House member: Former Rep. Matt Caldwell, a Republican who is now the property appraiser in Lee County. Emails show that Caldwell was involved with an IT company that also had discussions with the Hardee County Industrial Development Authority about a potential grant and co-locating with Grant and Brodeur’s company. That deal didn’t come together.

Brodeur features prominently in many of the records.

For instance, emails show that Brodeur took a trip to Wauchula in late July 2011 — about five weeks before he and his partners applied for the grant (and about eight weeks before they actually created LifeSync).

Brodeur went to Wauchula for a public hearing on redistricting, the once-a-decade process in which the Florida Legislature redraws the boundaries of the state’s legislative and Congressional districts.

But in addition to that public hearing, the emails show Brodeur also squeezed in a private meeting — with the executive director of the agency that ultimately gave LifeSync its grant.

“I enjoyed our time together today and appreciate your willingness to assist us in the process,” Brodeur wrote in a July 26, 2011, email to the executive director of the Hardee County Industrial Development Authority. “We remain committed to turning in a great application with a great product that should bring dividends to all involved!”

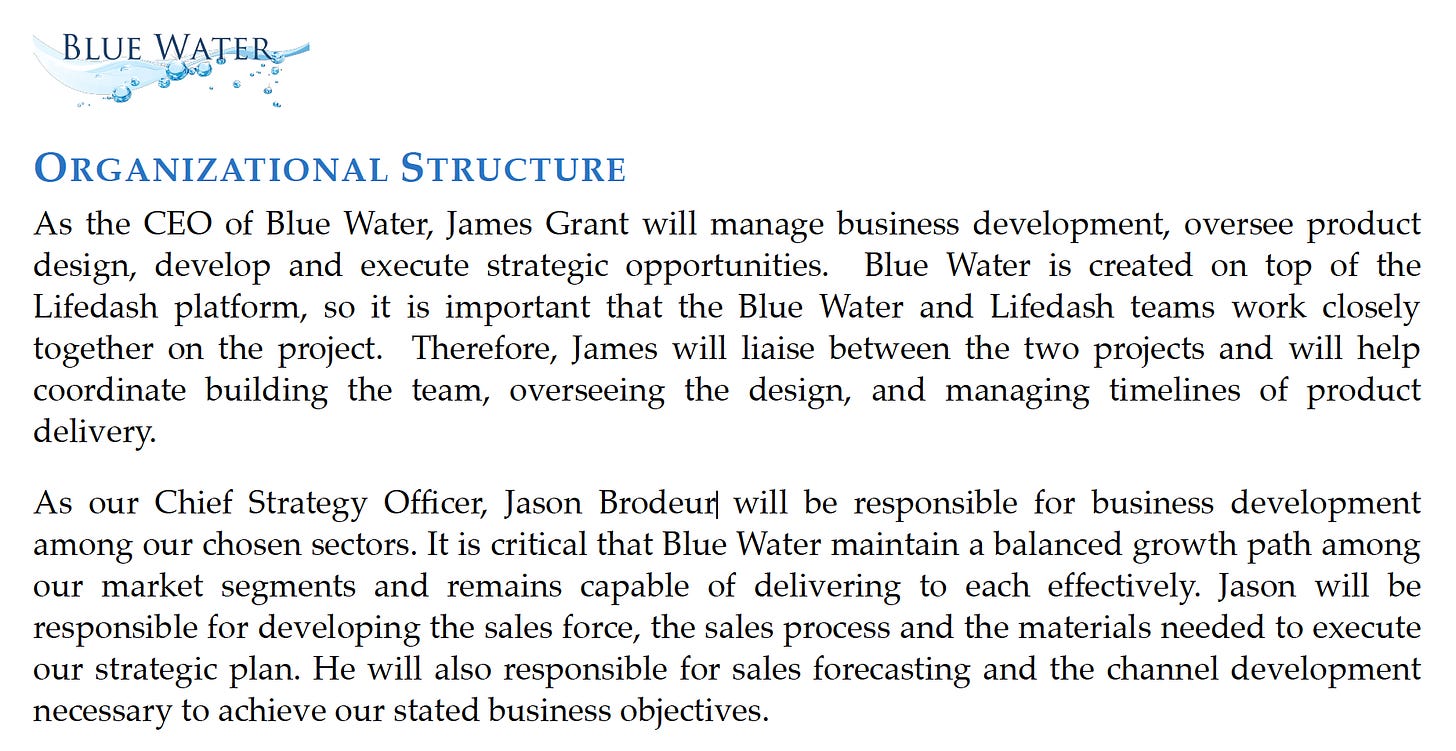

In addition, a proposed “business plan” prepared for the Industrial Development Authority refers to Brodeur as LifeSync’s “chief strategy officer.”

“Jason will be responsible for developing the sales force, the sales process and the materials needed to execute our strategic plan,” the business plan reads. “Jason will also be responsible for sales forecasting and the channel development necessary to achieve our state business objectives.”

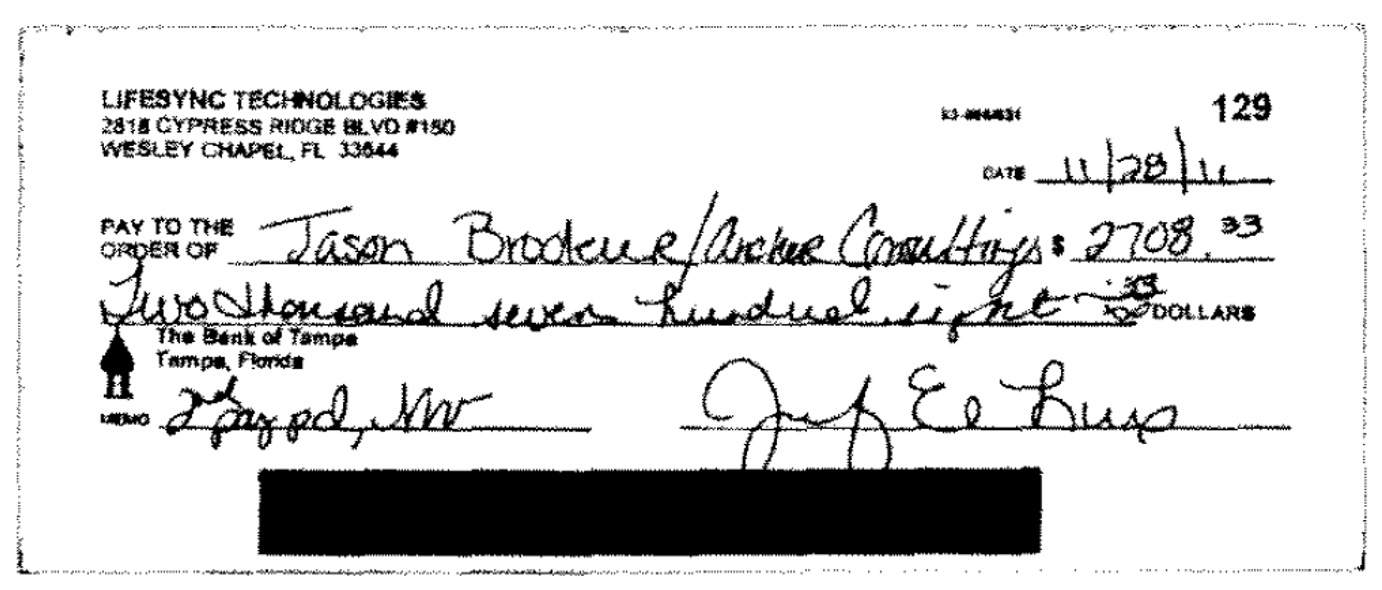

As part of the public-records litigation, a company that later took over LifeSync turned over monthly bank statements and canceled checks from LifeSync’s first year of operation. Those bank records show that LifeSync paid Brodeur just under $60,000 between October 2011 and September 2012.

The checks, issued to a company that Brodeur owns called “Anchor Consulting,” included nearly $11,000 in payments in the year 2011 alone. That’s potentially significant because it’s more than twice as much business income as Brodeur reported on his public financial disclosure form for 2011, which he was required to file as a member of the state House of Representatives.

Brodeur’s 2011 financial disclosure reports a little less than $5,000 of income from Anchor Consulting. It does not disclose LifeSync Technologies as a client.

It’s not clear what Brodeur did for that money.

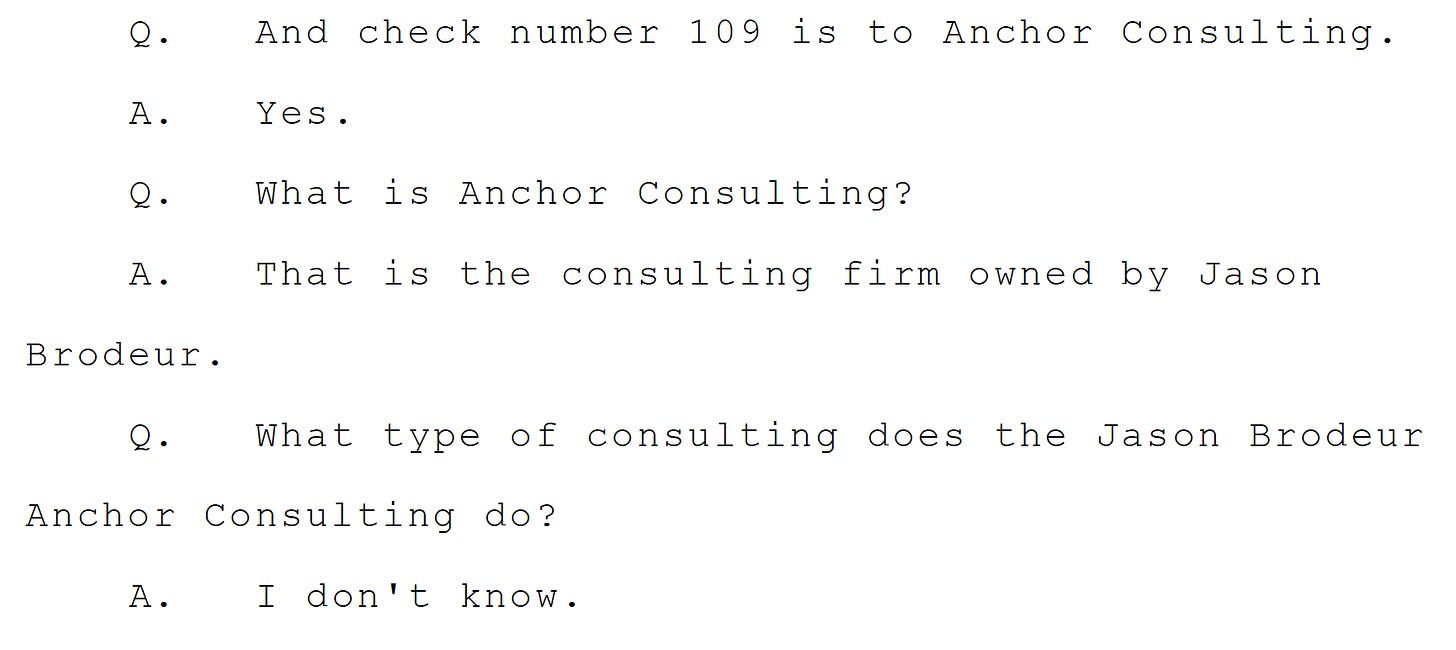

For instance, during a deposition, an attorney representing the plaintiff in the public-records case asked Bill Lambert, the then-executive director of the Hardee County Industrial Development Authority, about payments LifeSync had made to Anchor Consulting.

“That is the consulting firm owned by Jason Brodeur,” Lambert said.

“What type of consulting does the Jason Brodeur Anchor Consulting do?” the attorney asked.

“I don’t know,” Lambert replied.

Similarly, a private auditing firm hired by the Industrial Development Authority to review the LifeSync deal flagged payments to Brodeur’s consulting firm because the state legislator was acting as both an owner of, and a vendor to, LifeSync.

In a draft audit — which still has not yet been finalized — the auditors wrote that Brodeur had been paid for “marketing,” but that there was no agreement specifying the scope of services he was supposed to provide.

Still learning about a decade-old deal

One reason we’re only now learning many details about this decade-old economic development deal is that so many people involved fought hard to withhold information.

The various iterations of LifeSync, for instance, worked to block the release of key records by claiming they involved proprietary information and trade secrets.

And local economic-development officials took steps to keep their secrets, too. Lambert, the former executive director of the Industrial Development Authority, said in a deposition that he would sometimes read hard copies of LifeSync records in his pickup truck — rather than his office — and then return them to the company.

“So it was your intent by reading it in your truck that it would not become a...public record?” an attorney asked Lambert.

“I felt more comfortable,” Lambert responded. “I think had I taken possession of the records, had I viewed them in my office, I think that would have potentially compromised me and my ability to recognize their rights under 288.075.”

(That’s the state law that allows private companies trying to score public incentive deals to keep their records secret from taxpayers.)

Deeson, the Tampa reporter who broke the story, said it was difficult to get straight answers out of key players in real-time.

“Throughout the process I felt as if the public officials were lying to me almost every time they opened their mouths,” Deeson said. “Public records helped expose those lies.”

It’s possible that additional details about the deal will emerge in the coming weeks. Records show that Jamie Grant was deposed in June in the public-records lawsuit, though the contents of the deposition not yet been filed with the court.

In the meantime, all the former House members involved in the LifeSync grant continue to climb the ranks in Florida politics.

Albritton is now a state senator — and in line to become president of the Florida Senate in two years.

Grant is now Florida’s “chief technology officer,” appointed to the $157,000-a-year job by Gov. Ron DeSantis. (DeSantis picked Grant after Grant sponsored a bill rewriting the job qualifications required for the post.)

And Brodeur, like Albritton, has moved up to the Florida Senate, too — although Brodeur faces a far tougher re-election campaign this fall.

Chirp, chirp, chirp like a bird Greenberg.

Sounds like A Greenberg trick… birds of a feather? Consulting?? Consultants?