Lobbyist for a billionaire-run hedge fund wrote a bill allowing longer non-competes, records show

Bills to help corporations lock workers into longer non-compete agreements were given to lawmakers by a lobbyist for Citadel, a financial firm run by a billionaire investor and Republican megadonor.

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter and podcast devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the work of others — about Florida politics, with an emphasis on the ways that big businesses and other special interests influence public policy in the state. Seeking Rents is produced by veteran investigative journalist Jason Garcia, and it is free to all. But please consider a voluntary paid subscription, if you can afford one, to help support our work. And check out our video channel, too.

Lobbyists for a billionaire-run financial firm gave Florida lawmakers a bill that would help corporations stop workers from leaving for better-paying jobs or to launch new startup companies.

The controversial legislation, which is moving quickly through the state Capitol this session, would give businesses more legal power to bind workers to longer and stronger non-compete agreements — a type of clause in an employment contract that bars someone from working for a rival firm or starting a competing company of their own after their employment has been terminated.

Records obtained by Seeking Rents show that the initial draft of the legislation came from a lobbyist representing Citadel Enterprise Americas, the investment firm led by Ken Griffin, a billionaire hedge-fund manager and Republican megadonor.

Griffin, who has an estimated net worth of about $42 billion, recently moved Citadel from Chicago to Miami. And he has already become one of the biggest donors in state politics: Records show that Florida’s wealthiest billionaire after Jeff Bezos made more than $28 million in campaign contributions during the 2024 elections — including gifts of $4 million each to funds controlled by House Speaker Danny Perez (R-Miami) and Senate President Ben Albritton (R-Wauchula).

The Citadel lobbyist gave the proposal to Sen. Tom Leek (R-Ormond Beach) and Rep. Traci Koster (R-Tampa), both of whom then filed the legislation as bills in their own names, according to emails obtained through public-records requests.

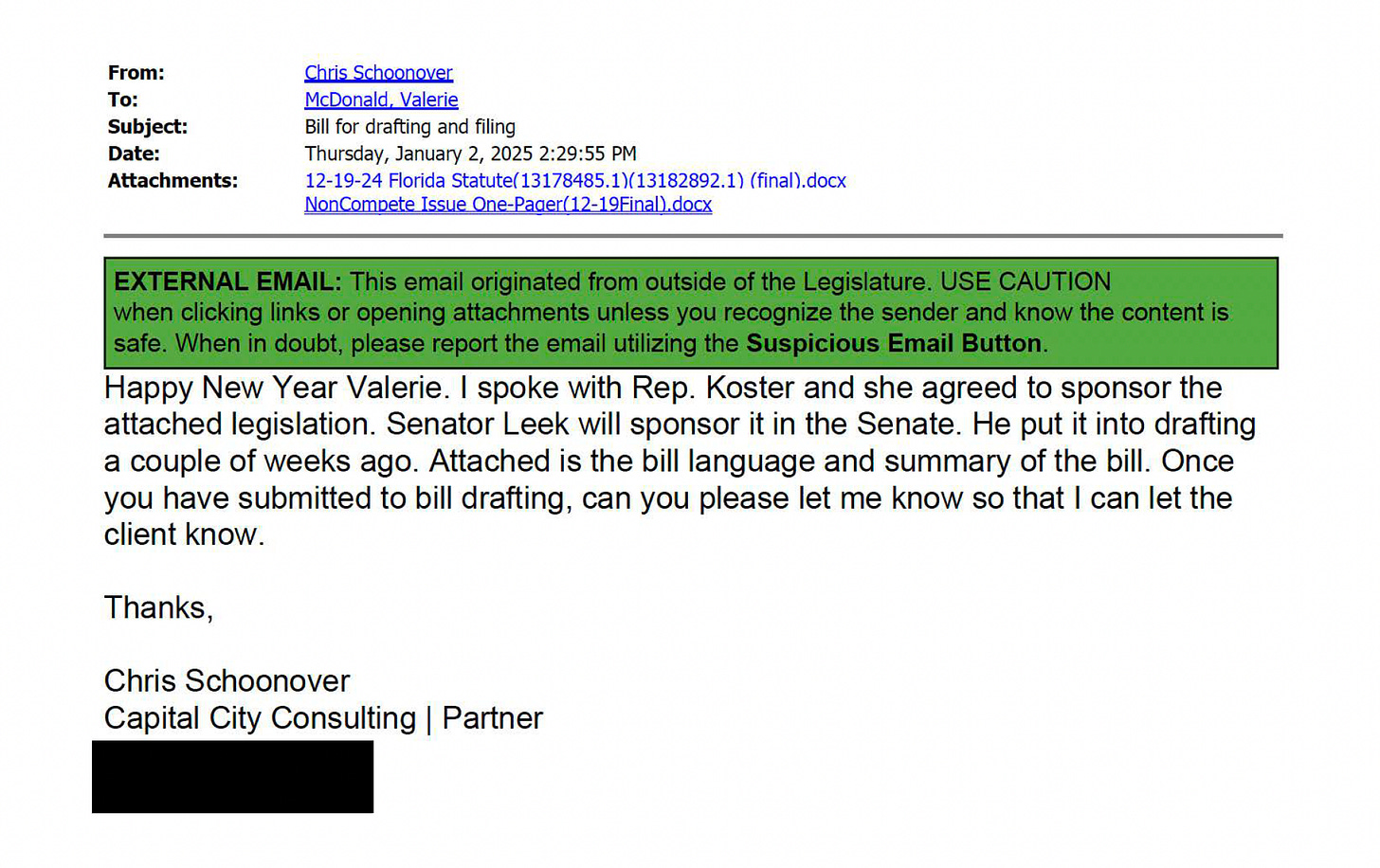

“I spoke with Rep. Koster and she agreed to sponsor the attached legislation,” Chris Schoonover, a lobbyist with the Tallahassee-based firm Capital City Consulting, wrote in a Jan. 2 email to one of Koster’s aides. “Senator Leek will sponsor it in the Senate. He put it into drafting a couple of weeks ago.”

“Once you have submitted it to bill drafting, can you please let me know so that I can let the client know,” Schoonover added.

The lobbyist did not identify the client. And disclosure records show that Citadel is one of a handful of companies that Capital City Consulting claims to be representing on the non-compete legislation.

But the proposal surfaced in Tallahassee just as Citadel is locking some of its workers into longer non-compete contracts. The business-news publication Bloomberg reported in January that Citadel has been extending non-compete periods for portfolio managers to 21 months. That’s significantly longer than non-compete policies at rival finance firms, Bloomberg reported.

Citadel is also currently suing a crypto-trading firm in Switzerland that was founded by former employees. Citadel claims the Swiss company stole trade secrets when it recruited another key employee who had been working on “high-speed products” for Citadel. Citadel also sued the former employee, accusing him of violating a non-compete agreement.

The new Florida legislation would empower companies like Citadel to enforce non-compete agreements anywhere in the world. It would also enable them to obtain immediate court injunctions should a rival company poach a valuable employee.

Citadel declined to comment.

That’s not all. Another email shows that a partner at the law firm Stearns Weaver Miller has also worked on the non-compete legislation. Citadel is a client of the firm.

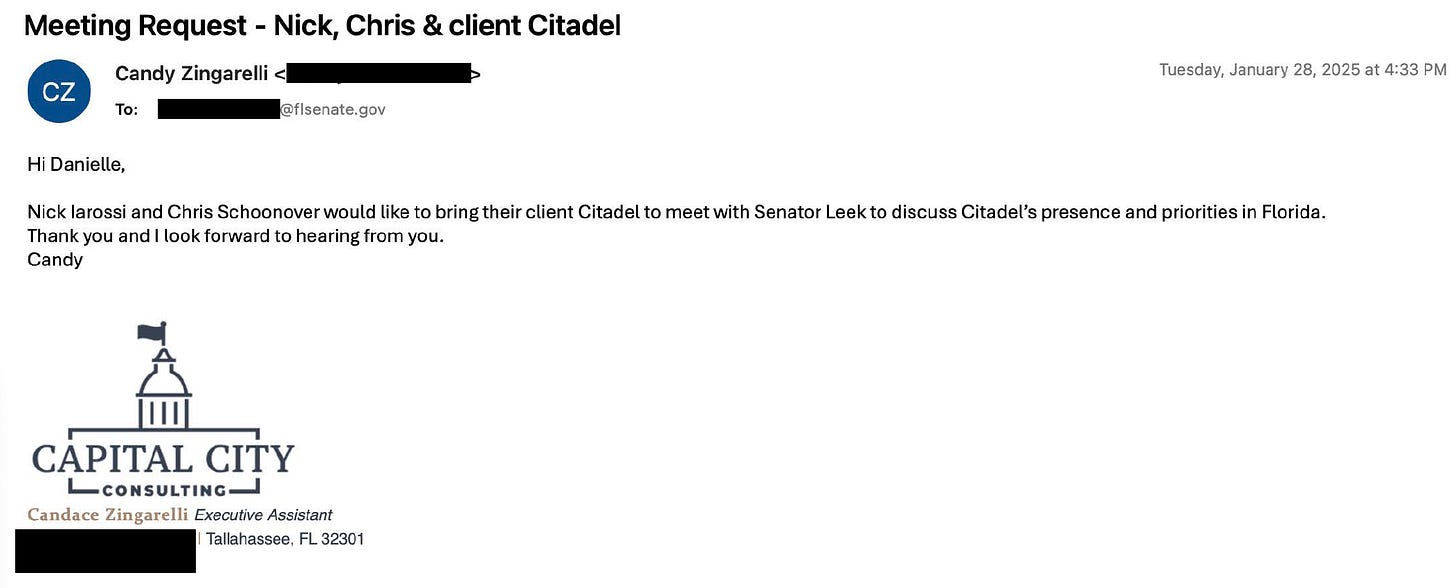

And a third email shows that Capital City Consulting arranged a meeting between Citadel and Leek a few weeks before Leek formally filed the non-compete legislation.

Leek did not respond to requests for comment.

Supporters have carefully avoided naming any specific company when discussing Senate Bill 922 and House Bill 1219 in hearings. And the public lobbying for the legislation has come through client-masking groups like Associated Industries of Florida.

But boosters have made clear that they they are trying to help financial firms who are afraid of losing knowledgeable employees.

“Florida is poised to be one of the finance capitals of the world,” Leek said during a recent hearing on the legislation. “And if we want to attract those kind of clean, high-paying jobs, you have to provide these businesses protection on the investment that they’re making.”

The bill sponsors have sometimes sounded as if they are reading from the same scripts when claiming Florida needs to allow stronger non-compete agreements, which are known in legal terms as a “restrictive covenant.”

“The current law in Florida on restrictive covenants is insufficient to protect industries in which employees routinely access sensitive business information,” Leek told the Senate Commerce and Tourism Committee on March 17.

“The current law in Florida on restrictive covenants, while perhaps workable for some industries, is insufficient to protect others in which employees routinely access sensitive business information,” Koster told the House Industries & Professional Activities Subcommittee two days later.

Florida law already permits companies to use non-compete agreements — but they can be difficult to enforce and are legally frowned upon. For instance, if an employer sues to enforce a non-compete against a former employee, courts are generally supposed to presume that any non-compete longer than two years is an unreasonable “restraint of trade.”

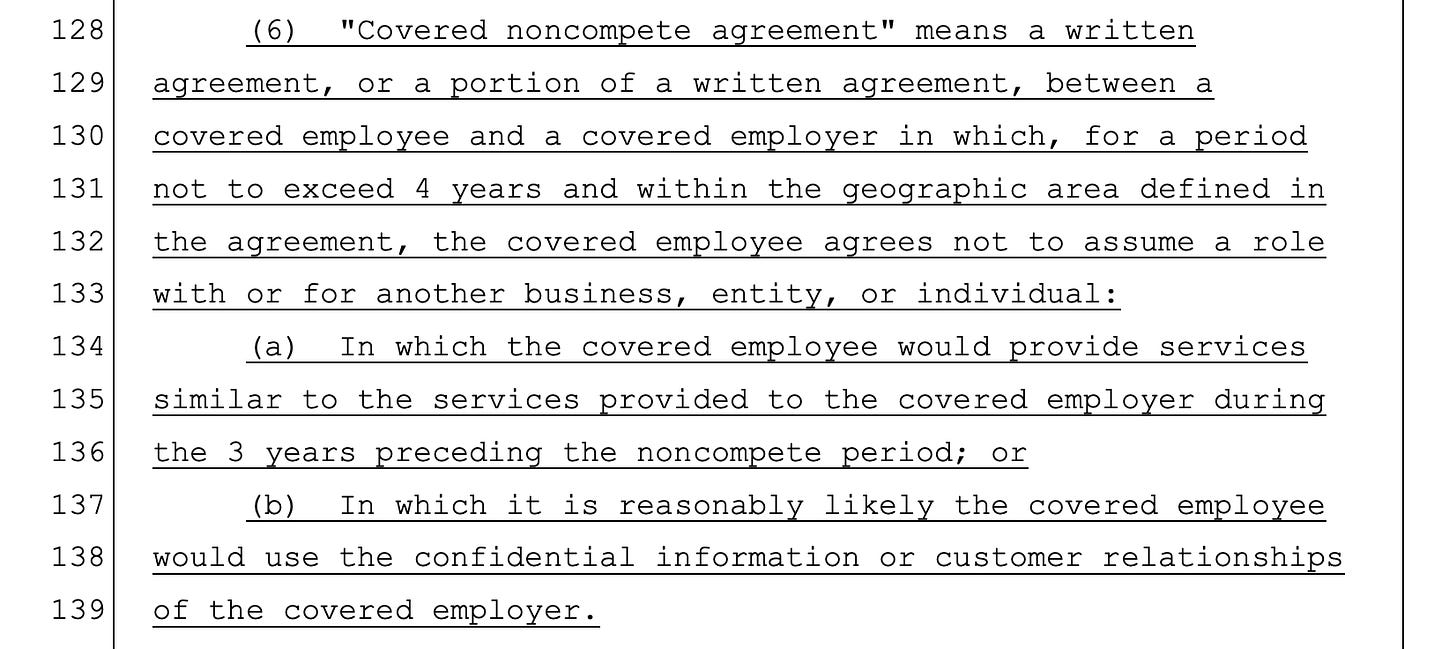

Senate Bill 922 and House Bill 1219 would authorize non-compete agreements that last up to four years. The bills would also make it much easier for companies to enforce them — by, for instance, forcing courts to issue immediate rulings that prevent an employee from working for another business if their former employee claims they are violating a non-compete clause.

Supporters insist they have narrowly tailored the legislation so that companies could only shackle certain workers to these tougher non-competes. But the changes could still hurt a broad swath of the workforce.

For instance, the legislation permits four-year non-competes for any worker making double the average annual wage in Florida — which supporters say would be about $120,000 a year.

But it would also allow companies to lock down workers at any salary level if the worker has “access” to “confidential information or customer relationships.”

That could have far-reaching impacts at a time when an estimated one in every five American workers is covered by a non-compete contract, and companies have used them to handcuff everyone from office janitors and television journalists to Massage Envy masseuses and Jimmy John’s sandwich-makers.

Non-compete contracts are also anti-competitive tools that prevent people from finding better-paying jobs or creating new companies in their chosen field of work. Every worker — from someone cooking the curly fries at Arby’s to a high-paid trader of cryptocurrency — should be free to move freely between employers or to start their own business whenever and wherever they choose.

The Federal Trade Commission estimated in 2023 that non-compete agreements suppress workers’ total earnings by between $250 billion and $296 billion a year.

The FTC attempted to impose a national ban on non-competes under the Biden administration. The rule was knocked down by the courts after big-business lobbying groups like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce sued.

It’s worth noting that while Florida’s Republican-controlled Legislature is advancing a bill to expand the use of non-competes, other states — including GOP-led ones — are working on bills to ban them entirely.

For instance, Wyoming recently became the fifth state to either ban or significantly restrict non-compete agreements, according to the law firm Nelson Mullins. The Ohio General Assembly is currently considering a Republican-backed bill to ban non-competes, too.

There are no good reasons for noncompete agreements. A company either has the ability to motivate and retain employees or it doesn’t.

Economic shackles like noncompetes should not be allowed to be included in any element the employee hiring, motivation and retention equations.

It's interesting that FL is doing something different than other states. Those "clean, high-paying jobs" must hold a lot of charm.