Local communities keep trying to help workers. Corporate lobbyists and Florida politicians keep teaming up to stop them.

A sweeping new bill in the Florida Legislature would prevent communities across the state from helping workers secure higher pay, stable schedules, and safer worksites from their employers.

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter and podcast devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the journalism of others — that examines the many ways that businesses influence public policy across Florida, written by Jason Garcia. Seeking Rents is free to all. But please consider a voluntary paid subscription, if you can afford one, to help support our work.

Urged on by lobbyists for some of the state’s biggest businesses, Republican lawmakers in Tallahassee have proposed new legislation that would crush local laws meant to make corporations pay higher wages, provide better benefits, or ensure safer workplaces.

The sweeping legislation would be a boon to low-wage employers like Walmart Inc. — and it was filed, coincidentally or not, on the very same day that Florida House Speaker Paul Renner (R-Palm Coast) pocketed a $25,000 campaign contribution from Walmart.

House Bill 433 would do three main things:

First, it would stop cities, counties and towns from making any business — even government contractors — pay their employees more than the minimum wage. That would dissolve a number of “living wage” laws that protect tens of thousands of workers in cities like Miami, Tampa and Gainesville.

Second, it would prevent communities from passing any other local laws regulating the “terms and conditions of employment.” That prohibition would cover a vast universe of potential ordinances — though it appears primarily aimed at stopping the spread of “fair workweek” laws that attempt to ensure more stable and predictable schedules for hourly workers.

And third, it would specifically preclude communities from protecting Floridians working in extreme heat. This comes as county commissioners in Miami-Dade County have been trying to craft a first-of-its kind law that would require employers to provide workers laboring in extreme heat with precautions like cool drinking water, regular breaks, and shade cover. Lobbyists for construction companies and agribusinesses have been fighting that effort.

The bill, which gets its first hearing Wednesday afternoon in the House Regulatory Reform & Economic Development Subcommittee, is an astonishingly anti-worker piece of legislation. It rolls up long-sought favors for Florida’s retail, tourism, construction, and agriculture industries into one ugly package.

It is also the latest offensive in a more than 20-year-long campaign by the state’s unified business lobby to weaken — and ultimately wipe out — even the most basic of labor protections for workers in Florida.

That campaign has been led by front groups like Associated Industries of Florida, the Florida Chamber of Commerce, the Florida Retail Federation, and the Florida Restaurant & Lodging Association — organizations that exist to push unpopular policies while protecting the brands of the corporations that fund them from any public backlash. Those lobbying groups and their members collectively spend millions of dollars a year on contributions to members of the Florida Legislature and statewide elected officials like the governor.

To cite just one example: House Bill 433 falls under the jurisdiction of the House Commerce Committee, which is chaired by Rep. Bob Rommel, a Republican from Naples. Rommel has taken more than $140,000 from AIF. He’s also taken more than $85,000 from the Florida Chamber of Commerce, more than $20,000 from the Florida Restaurant Lodging Association, and more than $5,000 from the Florida Retail Federation. And he’s taken thousands of dollars each from individual corporations like Disney, McDonald’s, Publix and Universal Studios.

But another part of the businesses lobby’s success has come from weaponizing Florida’s system of term limits, which forces lawmakers to vacate their seats after eight years and has led to continual turnover in Tallahassee. Organizations like AIF and the Florida Chamber have repeatedly negotiated “compromise” policies on things like minimum wages and benefits — only to push for even deeper cuts once newer crops of politicians cycle into office.

The lawmaker sponsoring House Bill 433 — Rep. Tiffany Esposito, a Republican from Fort Myers — was first elected to the state House last year.

So before this latest bill begins moving, it might be helpful to go back through that history to understand just how far the business lobby’s low-wage agenda has already advanced in Tallahassee.

1999

Let’s start all the way back in May 1999, just a few months after Jeb Bush was sworn in as Florida governor and the Republican Party finally captured complete control of state government.

That’s also when county commissioners in Miami-Dade County passed the state’s first minimum wage.

Often referred to as a living wage, Miami’s new minimum wage required many contractors doing business with county government to pay their employees roughly $3 more an hour than the federal minimum wage, which was just $5.15 an hour at the time. (Florida did not have a state minimum wage at all at the time.)

A few more cities and counties soon followed suit. Over the next couple of years, local leaders in places like Broward and Palm Beach counties and the cities of Miami Beach and Gainesville passed their own minimum wages, too. The new local wage laws were all limited solely to contractors — businesses that are, in other words, being paid by taxpayers.

But communities in other parts of the country were starting to adopt full minimum wages that covered all workers at any company doing business within a city or county.

2003

The state’s biggest businesses and their lobbying front groups turned to now-Republican-controlled Tallahassee for help. They got their wish in 2003 — sort of.

That’s when the Florida Legislature passed, and Jeb Bush signed, Senate Bill 54, which forbid — or “preempted,” to use legislative terminology — local governments in Florida from adopting city- or county-wide minimum wages.

But that bill also included a compromise: It allowed communities to continue making their own contractors pay a higher wage.

The business lobby signed off on this deal. Associated Industries of Florida, which explicitly supported the legislation, described it as a “politically viable compromise,” because “some legislators who are generally staunch opponents of government intervention in the free market are also opposed to legislation that interferes with the home-rule powers of local government.”

Remember that compromise. Because we’ll come back to it in a bit.

2004

In addition to preventing local governments from establishing full minimum wages, Bush and the Florida Legislature refused to establish a statewide minimum wage themselves. So Florida voters took matters into their own hands.

In 2004, Floridians overwhelmingly approved Amendment 4, the constitutional amendment that finally created a state minimum wage. The new Florida minimum was $1 an hour higher than the federal wage at the time. It was also indexed to inflation, so it could rise over time.

More than 70 percent of voters supported the amendment — despite a $4.5 million opposition campaign financed by low-wage employers like Burger King, Disney, Outback, Publix, Walgreen’s, Chili’s (Brinker International) and Olive Garden (GMRI Inc.).

2005

The constitutional amendment didn’t leave much wiggle room for politicians in Tallahassee to mess with. But they still tried to sand away at the margins.

The Bush administration chose to index the new minimum wage to a narrow measure of inflation that the business lobby hoped would suppress wage growth over time.

And the Florida Legislature passed Senate Bill 18B, a bill that, among other things, made it harder for workers who were illegally underpaid to hold their employers accountable. For instance, the bill prohibited courts from assessing any punitive damages against a business found to have violated the new minimum wage law.

The lawmaker who sponsored the bill in the state House had just been named “legislator of the year” by the Florida Restaurant Association (now the Florida Restaurant & Lodging Association).

2012

With local minimum wages seemingly now forbidden, advocates for workers turned their efforts to helping Floridians secure better benefits from their employers.

The first breakthrough came in Orange County — home of Orlando and heart of Florida’s low-wage tourism industry. In 2012, organizers gathered enough signatures to force a vote on a referendum that would have required any employer doing business in the county to provide its employees with sick leave.

This was a modest proposal. Only businesses with more than 15 employees would have had to provide paid sick leave, and employees would have had to slowly accrue the benefit over time. Small businesses would have to had to provide sick time, too, but it could have been unpaid.

That didn’t stop Orlando’s tourism giants from running to Tallahassee. Led by lobbyists for Disney, Universal Studios and the parent company of Olive Garden, the business lobby persuaded the Florida Legislature to pass, and Gov. Rick Scott to sign, House Bill 655, which barred cities and counties across Florida from any passing any kind of local laws that require employers to provide even minimal levels of benefits.

The new law killed Orange County’s sick-time referendum before residents could vote on it. But it also went a lot further than that: It blocked any potential local laws that might have made business provide benefits like health insurance, maternity or paternity leave, retirement plans or profit sharing.

2013-14

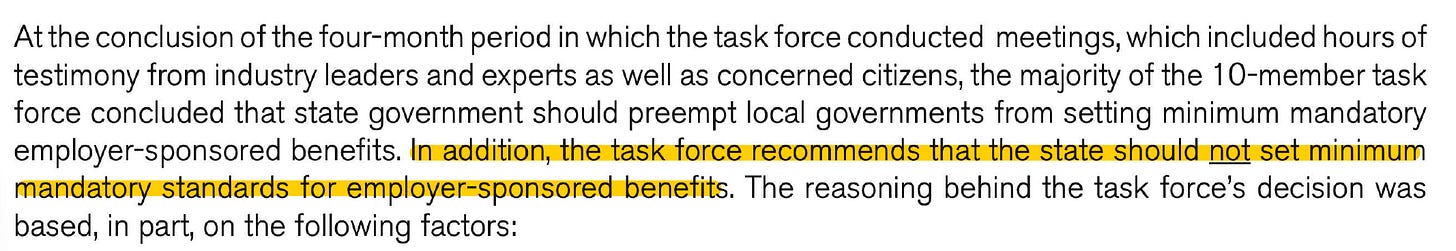

In response to criticism from workers and others, lawmakers inserted a provision into HB 655 that created something called the “Employee Sponsored-Benefits Task Force.” This new task force was charged with studying employee benefits in Florida and recommending whether Scott and the Legislature should set some statewide standard guaranteeing a basic level of benefits for all Florida workers.

The task force has held four meetings between September 2013 and January 2014 — soliciting input from groups Florida Chamber of Commerce, the Florida Retail Federation and the Florida Restaurant & Lodging Association.

The task force’s conclusion? That Rick Scott and the Florida Legislature do nothing at all.

2016

Now, when Florida voters passed Amendment 4 back in 2004, they didn’t just establish a statewide minimum wage. They also put a leash on the Florida Legislature.

That’s because the amendment included a provision that implicitly forbid state lawmakers from passing any laws weakening the new wage. That sparked a debate about whether Senate Bill 54 — the 2004 legislation that prevented cities and counties from setting higher minimum wages of their own — was now unconstitutional.

The city of Miami Beach decided to test it. In 2016, city commissioners passed a new ordinance establishing a citywide minimum wage — one that applied to all employers, not just government contractors. The new wage in Miami Beach, one of the most expensive cities to live in in all of Florida, was about $2 an hour higher than the statewide minimum wage at the time.

Florida’s Big Business lobby went ballistic. The Florida Chamber of Commerce, the Florida Retail Federation and the Florida Restaurant & Lodging Association all sued, arguing that Miami Beach had just broken state law.

And once again, they enlisted more help in Tallahassee. Though this time it came from then-Attorney General Pam Bondi, who threw the state’s weight behind the business lobby by joining the lawsuit on their side.

Bondi is now a partner at Ballard Partners, Florida’s biggest lobbying firm, with a roster of clients that includes Amazon, Walgreen’s and U.S. Sugar Corp.

2017

Remember that 2004 compromise? The one in which Jeb Bush and the Legislature decided to stop local communities from setting city- or county-wide minimum wages — but allowed them to set minimum wages for their own contractors.

A few years later, the business lobby set out to undermine that deal.

One of the first changes came in 2017, when the Legislature passed, and Gov. Rick Scott signed, House Bill 599, which prohibited local governments from setting minimum wages on construction contracts for public-works projects — stuff like roads, buildings, power plants and sewer systems.

But this bill included its a new compromise: It only applied to construction contracts for which the state was providing at least half of the funding. If a city or county wanted to foot more than half the bill itself, it could still make the construction firm profiting off the deal pay its workers a higher wage.

2018-19

The Florida Chamber of Commerce, the Florida Retail Federation and the Florida Restaurant & Lodging Association won the first few rounds in their lawsuit against Miami Beach’s minimum wage. But the city scored a big victory in August 2018, when the Florida Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

Florida’s highest court was, at the time, led by three senior justices who had all been appointed before Republicans gained complete control of state government. They had thrown out a number of high-profile laws that big businesses had lobbied through the Legislature over the years.

The decision to take up the Miami Beach case had been close: The seven-member court voted 4-3 to hear it, with all three of those senior justices voting in favor. If the court hadn’t done so, a lower court ruling invalidating the city’s minimum wage would have been the last word — and the business lobby would have won.

But then two things happened in January 2019: The three senior justices reached the mandatory retirement age. And Ron DeSantis was sworn in as Florida’s new governor.

DeSantis immediately replaced them with three justices who were far more deferential to the Florida Legislature. Two of DeSantis’ appointees — Barbara Lagoa and Carlos Muniz — used people who are now lobbyists at Ballard Partners as personal references.

Just a few weeks after DeSantis appointed the new justices — and just a few weeks before oral arguments in the Miami Beach minimum wage case — the revamped Supreme Court closed the case.

With both Lagoa and Muniz joining a new majority, the court voted 5-2 to cancel the oral arguments and let the lower court ruling stand. Miami Beach’s minimum wage was eliminated. The business lobby had won.

They weren’t satisfied. A few months later, the Legislature passed, and DeSantis signed, House Bill 829, a piece of legislation that punishes any city or county that defies a state preemption by forcing them to pay the attorney fees of whoever successfully sues them.

The Chamber of Commerce, the Retail Federation and the Restaurant & Lodging Association all lobbied in favor of that bill.

2020

Floridians took matters back into their own hands in 2020, passing Amendment 2, which raised Florida’s minimum wage to $10 an hour — and put it on a path to $15 an hour by Sept. 30, 2026.

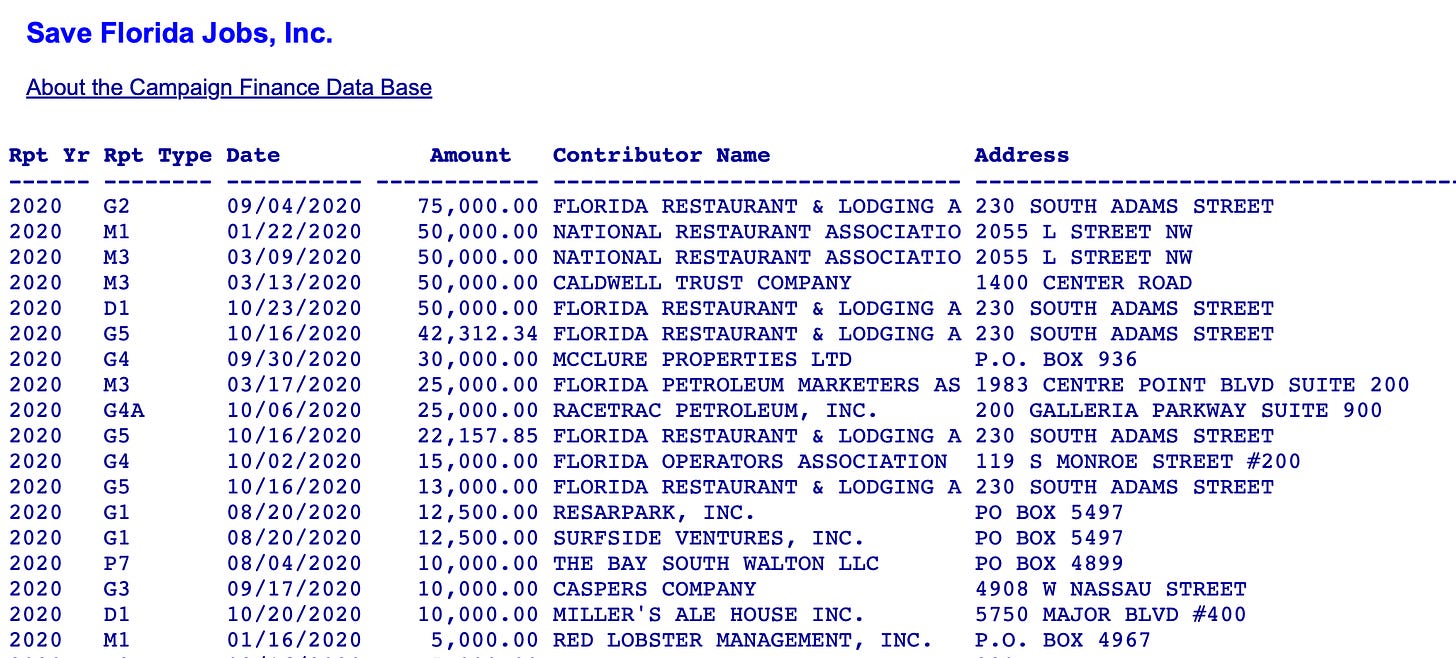

The amendment passed with more than 60 percent support, despite DeSantis himself instructing Floridians to vote no. Records show that the Florida Restaurant & Lodging Association and the National Restaurant Association spent at least $300,000 combined on an opposition campaign.

Florida lawmakers immediately floated a plan to let businesses ignore the minimum wage for certain “hard-to-hire” workers. That idea, at least, went nowhere (probably because voters would have had to approve it.)

2021

Remember that second compromise back in 2017? The one in which Rick Scott and the Legislature stopped cities and counties from making their construction contractors pay a higher wage — but only on projects for which the state was footing more than half the bill.

That second compromise lasted for four years. In 2021, the Legislature passed, and Ron DeSantis signed, House Bill 53, which stopped cities and counties from setting a minimum wage on any construction contracts using a single dollar of state funds.

But now there was a third compromise: This new, stricter preemption only applied to construction projects valued at $1 million or more. Local governments could still require higher wages on smaller public-works projects, even if they were funded with a bit of state money.

You can probably guess what happened next.

2023

Business lobbyists and their allies in the Legislature piled on in an especially big way this past session.

Lawmakers passed Senate Bill 346, which eliminated the $1 million threshold on construction contracts. So now local governments are forbidden from making construction firms pay their workers a higher wage on any public-works project at all if it uses any amount of state funding.

They also passed Senate Bill 170, which gives businesses even more legal ammunition to sue cities and counties and block any local laws a business doesn’t like. Associated Industries of Florida, the Florida Chamber of Commerce, the Florida Retail Federation and the Florida Restaurant & Lodging Association all lobbied for that one.

And the Legislature passed Senate Bill 892, a small but especially Scrooge-like bill that cut minor league baseball players out of the state’s minimum wage. Records showed the legislation was written by lobbyists for Major League Baseball and its billionaire team owners — lobbyists at Ballard Partners

Ron DeSantis signed all three bills into law.

2024 — and beyond

That brings us back to today — and to House Bill 433, the most extreme bill we’ve seen yet in Tallahassee, at least in terms of cutting off local communities trying to help Florida’s workers achieve a minimum level of economic stability.

(Not to be overlooked, Republican lawmakers have also filed a narrower bill that would bar local minimum wage requirements on all public construction projects — even on projects paid entirely with local money.)

But if the last 25 years have proven anything, it’s the Big Business lobby won’t stop here. Even if House Bill 433 passes this session and Ron DeSantis signs it into law, Associated Industries and the Florida Chamber and all the rest will be back again pushing for more ways to squeeze workers into submission.

And while there’s no way to know for sure what will come next, it’s worth remembering that Ron DeSantis and the Legislature have flirted with pulling Florida out of the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

That would put politicians in Tallahassee in charge of workplace safety.

Thanks, but

My head already hurts from all the bad news this am., & my arm has tendinitis from playing whack-a-mole with everything Repubs keep throwing at us.

Low wage workers in Florida, are being treated like slaves by Florida's totally controlled Republican legislature. This only gets worse with corporate payoffs to their campaigns and the undermining of Home Rule in Florida. Home Rule powers ensure that the cities are effectively and efficiently providing for the wishes of their citizens. Cities are publicly created, independent governments designed by their citizens, for their citizens. They are the only voluntary level of local government in the Sunshine State.