Records show Big Sugar lobbyists are working on plans for an Everglades-area mine

Boosters of the Big Sugar-backed mine have approached senior aides to Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis for help with the controversial project.

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter and podcast devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the work of others — about Florida politics, with an emphasis on the ways that big businesses and other special interests influence public policy in the state. Seeking Rents is produced by veteran investigative journalist Jason Garcia, and it is free to all. But please consider a voluntary paid subscription, if you can afford one, to help support our work. And check out our video channel, too.

Late last month — between Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve, a period when few people were paying attention to politics — the state agency responsible for restoring the Florida Everglades suddenly made a major decision.

Without any public debate, the South Florida Water Management District issued a letter removing a legal barrier standing in the way of a rock mine that the sugar industry wants to open south of Lake Okeechobee — on land that was once a part of Florida’s famed River of Grass.

The so-called “letter of project identification,” which could enable the Big Sugar-backed mine to qualify for a key local permit, was signed by Drew Bartlett, the executive director of the water management district.

But records show he had help writing it.

Emails obtained by Seeking Rents show that an initial draft of the letter was given to Bartlett by an executive at Phillips & Jordan, the construction contractor hired to build the roughly 13-square mile rock mine.

And electronic metadata on that draft show the original author was an executive at U.S. Sugar Corp. — which, along with fellow sugar producer Florida Crystals, owns the limestone that would be strip-mined from the land, crushed into aggregate, and sold as construction material.

That’s not all. The emails also show that project lobbyists have pitched the proposal directly to senior aides to Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who appoints the leaders of the South Florida Water Management District. And while DeSantis has publicly clashed with the sugar industry in the past, campaign-finance records show that the Republican governor recently cashed a $100,000 check from Phillips & Jordan.

Supporters are even angling for taxpayer subsidies for the project, which they are pitching as an environmental asset because the resulting mine pit would be converted into a water-storage reservoir. A presentation given to the South Florida Water Management District staff over the summer notes that the “project team will work with state agencies to request grants and appropriations.”

Taken together, the records offer a glimpse at the many ways in which the sugar industry and its supporters are working behind the scenes to win approval for the controversial mining project — amid intense opposition from Everglades activists, who say a massive new mine in the region could undermine the most important and expensive environmental restoration project in Florida history.

The Governor’s Office declined to answer questions about the proposed mine — including whether DeSantis personally supports it or whether his staff has ordered water district staffers to help push the project forward.

Private mine, public reservoir

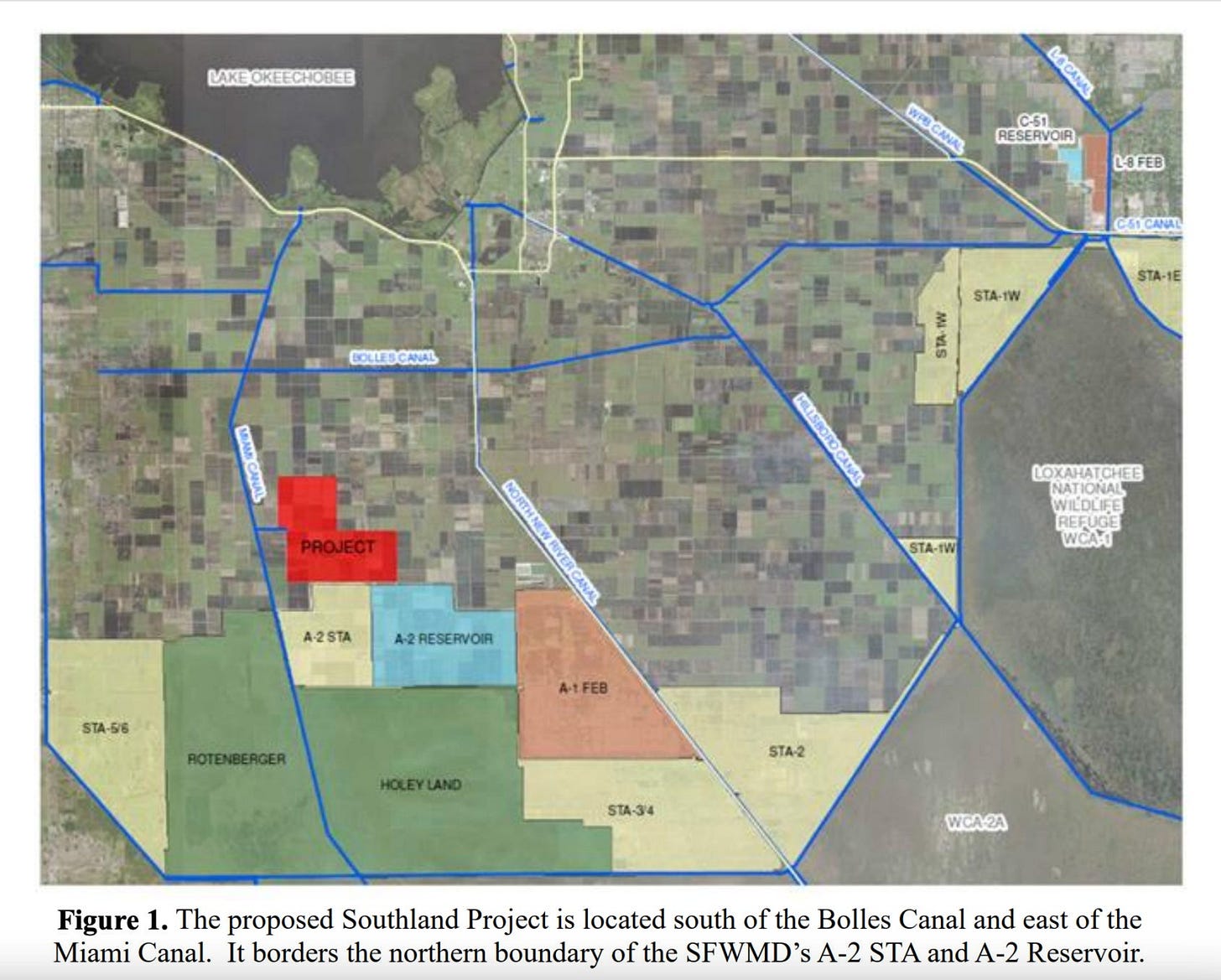

It’s called the “Southland Water Resource Project.” And it has been in the works since at least October 2023, when a manager at Phillips & Jordan first publicly mentioned the idea during a meeting of the South Florida Water Management District.

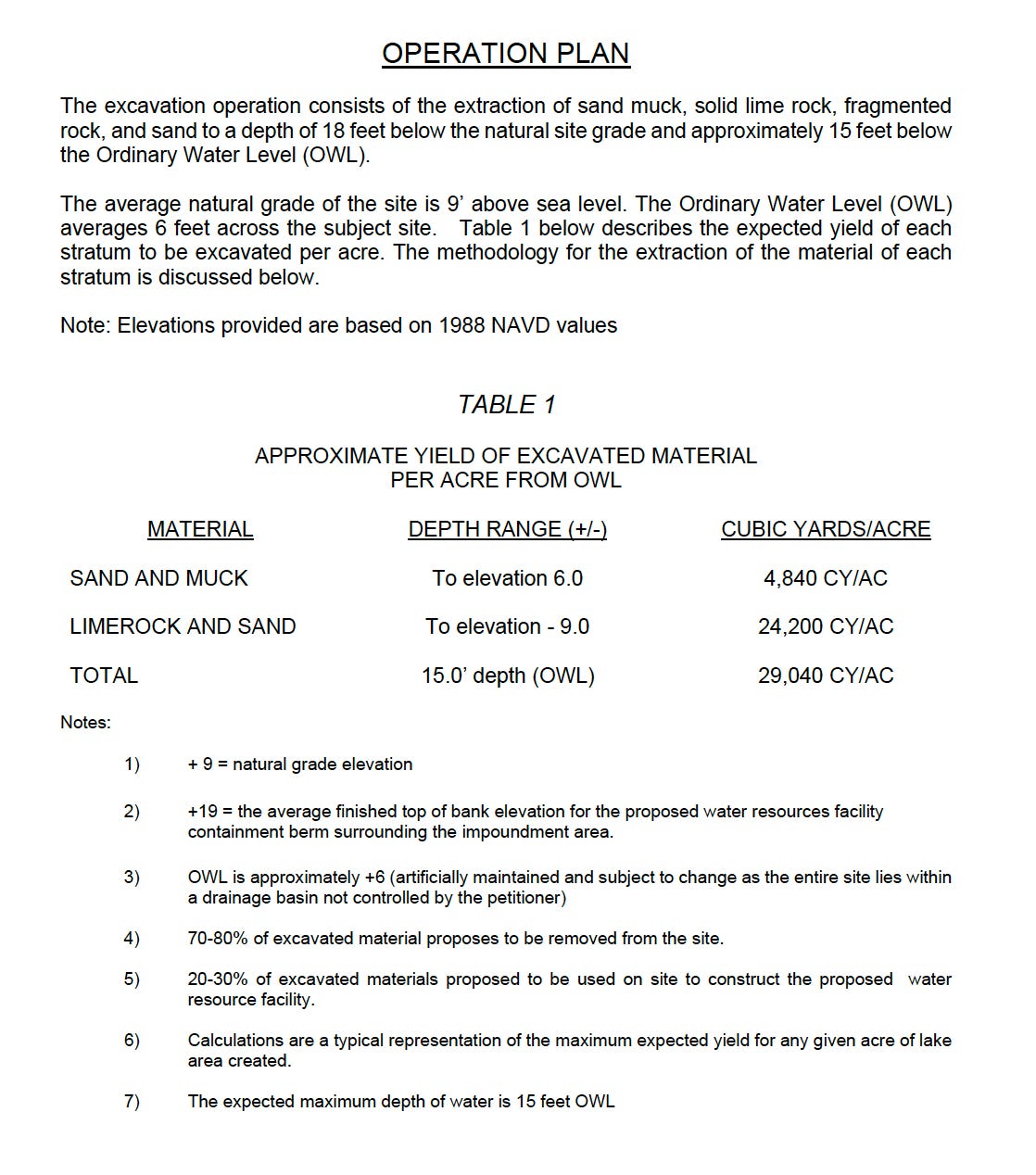

Southland is, first and foremost, a mine. Documents submitted to Palm Beach County show that operators would blast and scrape to a depth of about 15 feet across most of a nearly 9,000-acre site in what’s known as the “Everglades Agricultural Area.”

Plans call for excavating as much as 9.4 million tons of sand and limestone each year for roughly 30 years. About 75 percent of the material would be processed at an on-site factory, where it would be washed, crushed, shifted, sized, and eventually shipped away by rail.

Much of the crushed rock is expected to be sold as aggregate to the Florida Department of Transportation for use in road construction. The plans say the site could include a concrete and asphalt plant and an FDOT testing lab.

But once the rock has been dug up and sold, Southland would get a new purpose: Water storage. Boosters have promised to transform the exhausted mine into an in-ground reservoir capable of holding as much as 40 billion gallons of water.

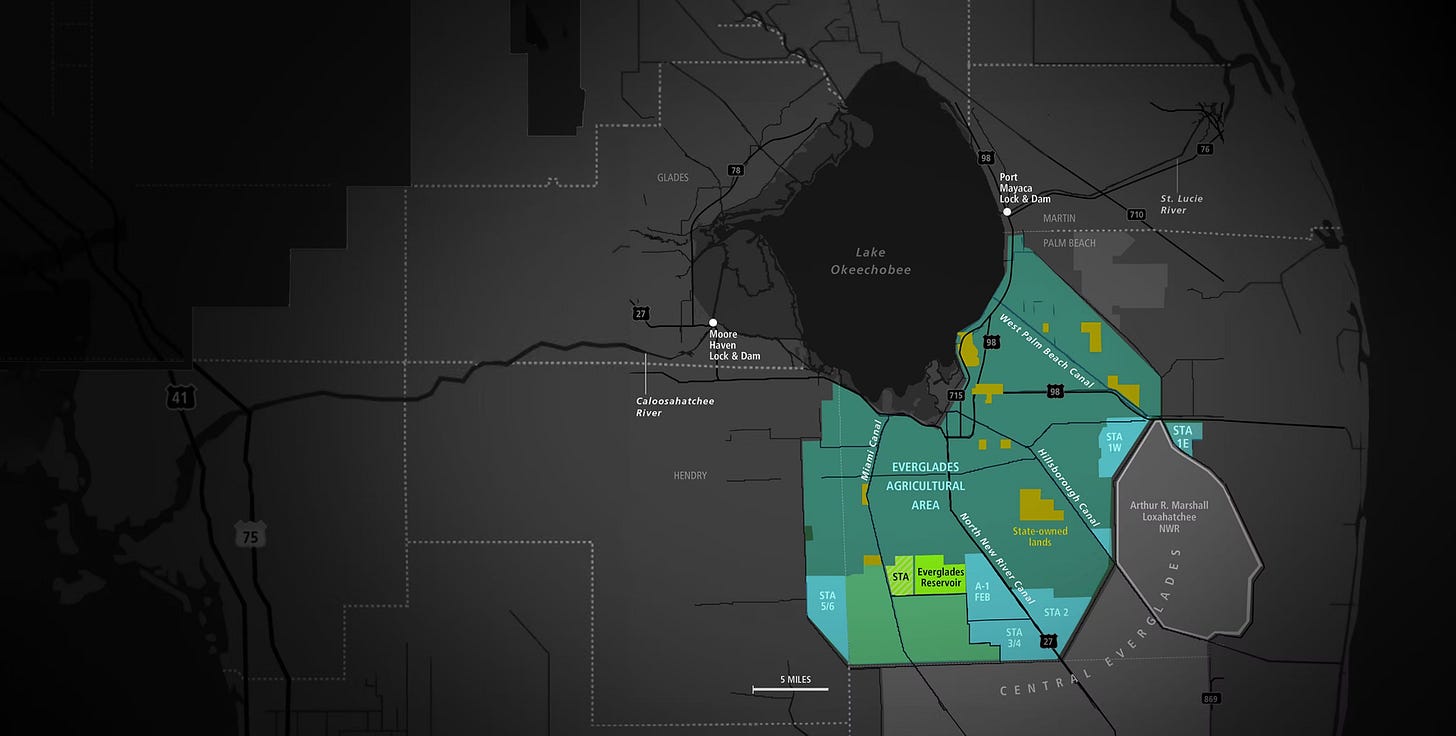

Water storage capacity is critical to Everglades restoration — especially south of Lake Okeechobee, which is filled with polluted water that must be released when the lake gets too full. That can fuel blooms of toxic algae along the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie Rivers and their coastal estuaries.

Storing more of Lake O’s water in reservoirs south of the lake reduces the need for coastal discharges. But it also provides a source of water that can, once it is clean, be released south into the Everglades, restoring some of the slow-moving river’s natural flow.

In fact, Southland would be built next to the soon-to-open “EAA Reservoir” — which will provide nearly 80 billion gallons of water storage south of Lake O and which environmental groups say is the most critical project in a multi-decade Everglades restoration plan.

Southland supporters have used the mine’s second act as a storage reservoir to pitch it as a “public private partnership,” or P3 project, with the South Florida Water Management District. Records show that Southland submitted a formal P3 application to the water district on July 3 — just days after a new state law went into effect allowing developers to submit unsolicited P3 projects to government agencies around the state.

But environmental groups and Everglades activists are opposed.

For one thing, they say that a 15-foot-deep pit of water is of little environmental value unless it also includes additional stormwater treatment areas — networks of wetlands that can filter and clean the water so it can actually be released into the Everglades. The EAA Reservoir, for instance, includes roughly 10,500 acres of storage. But it also comes with 6,500 acres of stormwater treatment areas.

They also say that approval of Southland could lead to widespread mining throughout the Everglades Agricultural Area, as more sugarcane fields grow fallow following decades of farming and the sugar industry looks for new ways to monetize its land.

And they are skeptical of the sugar industry’s motives — particularly given that the industry has fought to stop the EAA reservoir from opening.

It’s not clear how much U.S. Sugar, Florida Crystals and their contractors stand to pocket as profit from the Southland project. Captains for Clean Water, a conservation group opposed to the project, estimates that the mined rock could be worth $800 million.

Amanda Bevis, a spokesperson for Phillips & Jordan, declined to say whether the companies involved have estimated the value of the aggregate material they would mine.

Bevis did say, though, that the water that would eventually be stored in the reservoir would be controlled by the state rather than the companies themselves.

“Water resources that are stored in Southland are under the authority of the state,” Bevis said.

Politically connected companies

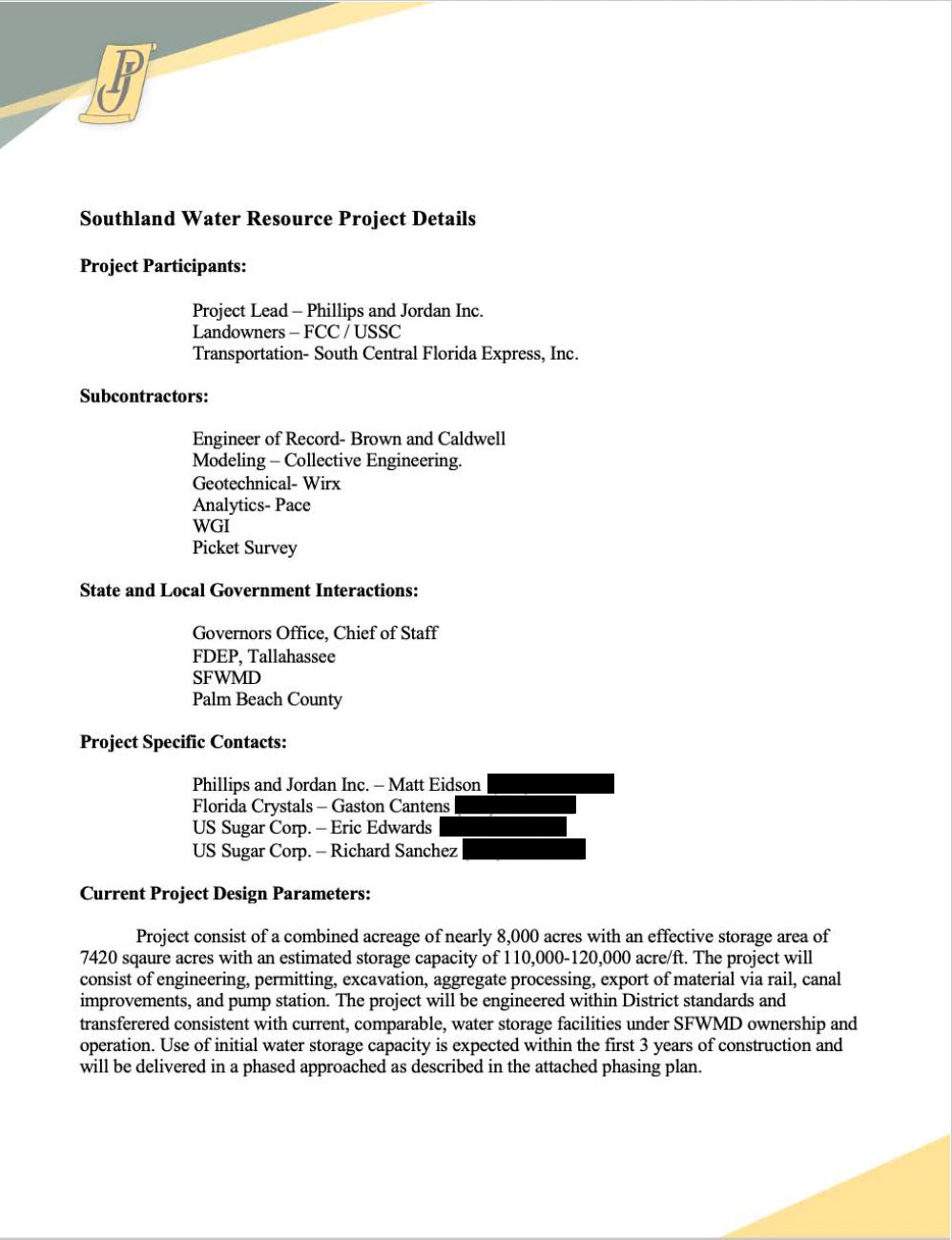

Based in Knoxville, Tenn., Phillips & Jordan is the project lead on Southland and the company name that appears on most of its public filings.

But records obtained through a public-records request show that Florida’s two Big Sugar companies are deeply involved.

For instance, one document provided to South Florida Water Management District shows that U.S. Sugar and Florida Crystals own all the land to be mined. The document also identifies four “project specific contacts:” An executive at Phillips & Jordan, a lobbyist Florida Crystals, and two lobbyists at U.S. Sugar.

That same document also shows that some of those project lobbyists have interacted directly with the highest levels of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ office — including his chief of staff.

DeSantis’ chief of staff is James Uthmeier, who is one of the governor’s closest and most powerful aides. In fact, DeSantis recently announced that he will soon make Uthmeier Florida’s next Attorney General. The job is coming open because DeSantis picked current Attorney General Ashley Moody to succeed Marco Rubio in the U.S. Senate, after President Donald Trump appointed Rubio his new Secretary of State.

Uthmeier also personally led a political committee set up last year to defeat a ballot initiative that would have legalized marijuana in Florida. Defeating that amendment was one of DeSantis’ top priorities during the election — and the Uthmeier-led committee took millions of dollars from a dark-money group with links to Big Sugar.

U.S. Sugar, Florida Crystals and Phillips & Jordan are each among the largest corporate contributors in all of Florida politics. Campaign-finance records show, for instance, that U.S. Sugar and Florida Crystals showered more than $3 million each on Florida politicians and political groups in 2024 alone.

Phillips & Jordan, meanwhile, made more than $1.7 million in state-level contributions last year — including a $100,000 gift directly to DeSantis’ “Florida Freedom Fund” in November.

Clearing a key hurdle — with help

There’s a legal reason why it’s so important to the sugar industry that the Southland project be seen as a water-storage reservoir rather than a rock mine.

That’s because it’s in the Everglades Agricultural Area. And zoning rules in Palm Beach County — which have been buttressed by a series of court rulings that stopped previous mining projects — severely restrict mining in the area.

But Palm Beach County’s rules include some narrow exceptions for mines. And one of those exceptions kicks in when the mining will occur on a site that has been identified by the South Florida Water Management District and that will be used to provide “viable alternative water technologies for water management.”

As a result, Southland supporters have spent months lobbying the water management district to issue what’s known as a “letter of project identification.”

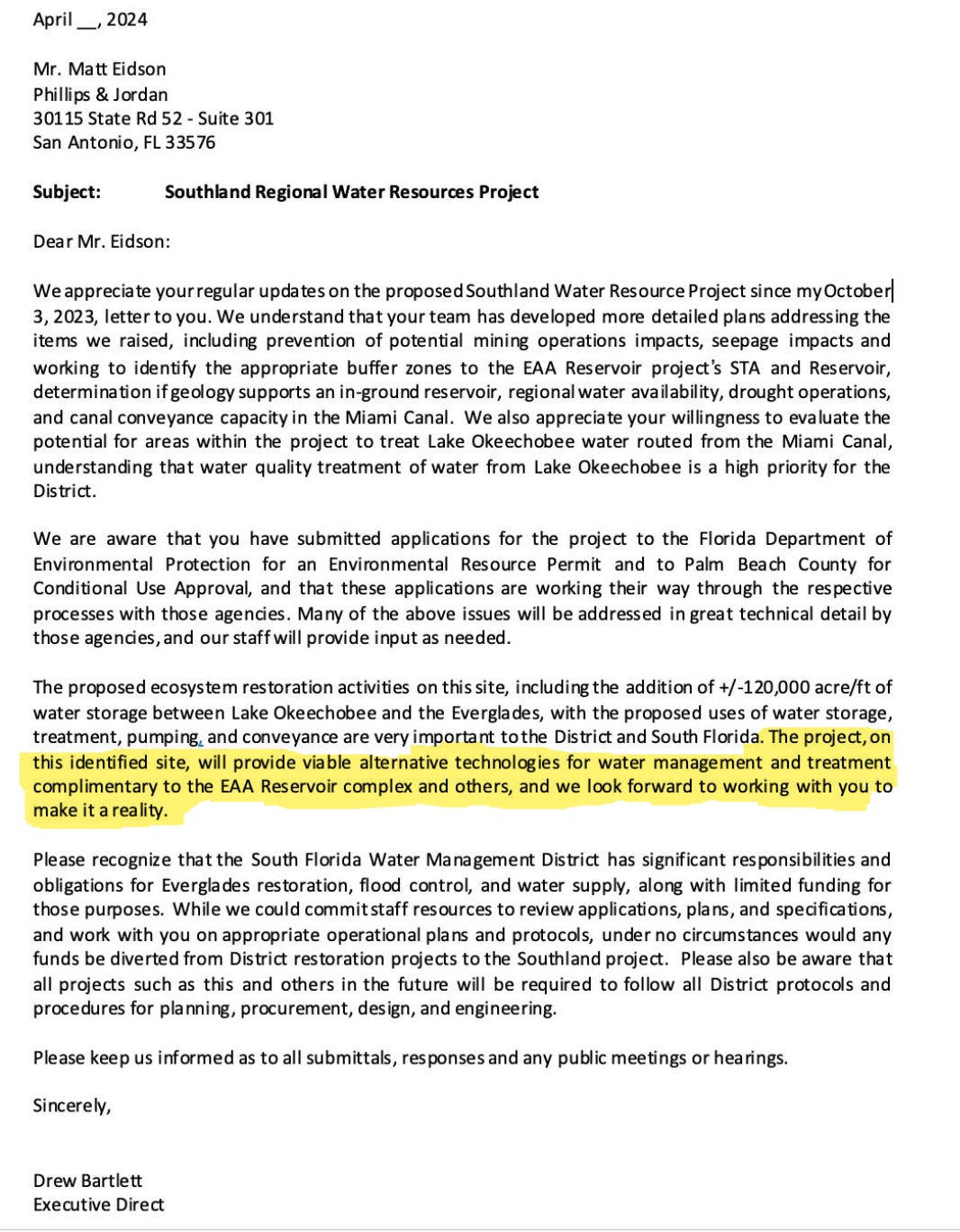

In April, for instance, records show that Matt Eidson, an executive at Phillips & Jordan, emailed a draft letter to Drew Bartlett, the water district’s executive director — a letter for Bartlett to sign in his own name and then send back to Eidson and Phillips & Jordan.

“As we discussed please review the attached letter for the Southland Water Resource project,” Eidson wrote in the April 19 email. “If acceptable we would appreciate your execution.”

Metadata on the underlying document identify the author as Richard Sanchez, an executive at U.S. Sugar Corp. And the letter contained the magic words needed to qualify the project for a permit from Palm Beach County.

“The project, on this identified site, will provide viable alternative water technologies for water management and treatment complimentary to the EAA Reservoir complex and others,” the draft letter reads.

A few months later, shortly after Phillips & Jordan had submitted its formal P3 application to the water management district, Eidson emailed a project update to district staff.

Under a heading titled “next steps for the project,” the company again asked for a project identification letter. The document also noted that a “correspondence draft” had already been submitted to the district.

The South Florida Water Management District didn’t issue the letter right away. And the Southland project quickly became consumed in controversy as environmental groups — some of whom have worked closely with DeSantis and the water district on Everglades conservation — raised alarms.

The blowback was so strong that Southland supporters abruptly withdrew their P3 application in September.

Until, that is, Christmas.

Records show that Phillips & Jordan resubmitted a proposal on Dec. 24 — Christmas Eve, a day when state offices across Florida were closed for the holiday.

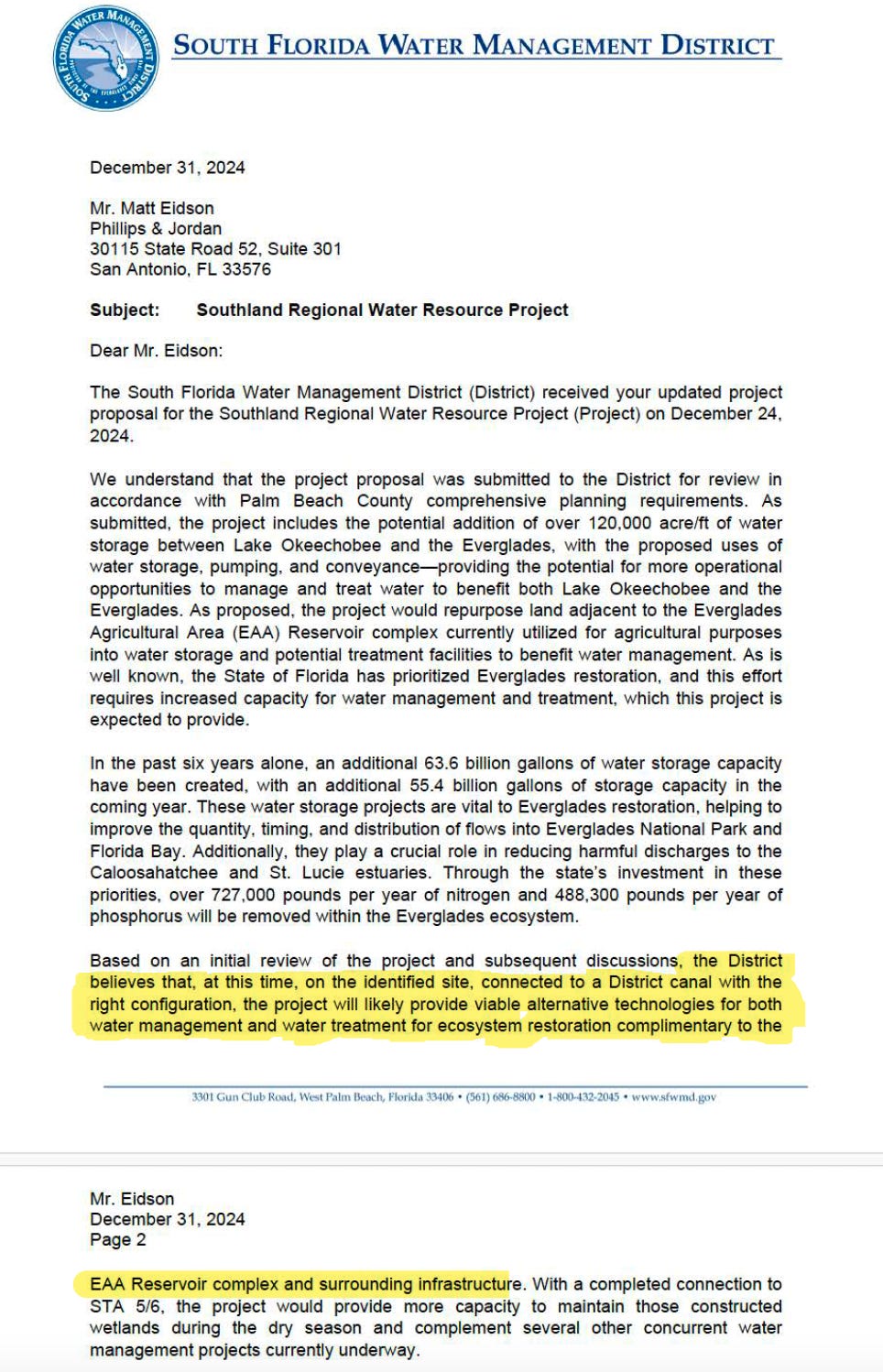

And this time, the South Florida Water Management District acted almost immediately. Exactly one week later — on New Year’s Eve, another day when state offices were closed — district executive director Drew Bartlett gave Southland its letter of identification.

“…the District believes that, as this time, on the identified site, connected to a District canal with the right configuration, the project will likely provide viable alternative technologies for both water management and water treatment for ecosystem restoration complimentary to the EAA Reservoir complex and surrounding infrastructure,” Bartlett wrote, using similar language as the earlier draft from Philips & Jordan and U.S. Sugar.

It’s not clear why Bartlett issued the letter himself rather than asking the water management district’s board of directors to provide direction. In earlier emails, he seemed intent on bringing Southland up for a public discussion before the DeSantis-appointed board.

“I am not going to use my ED [executive director’s] report to discuss this item because we would be seeking board direction on whether to proceed,” Bartlett wrote in a July email to Eidson of Phillips & Jordan.

Bartlett declined to answer specific questions about the project, including why he acted without seeking board direction — or whether anyone in the Governor’s Office asked him to issue the letter.

The battles ahead

There may still be some big battlegrounds ahead.

Palm Beach County, for instance, must still approve a permit for the mining operation, which will likely require a public vote of the county commission. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection — which is also run by a DeSantis appointee — must issue a permit of its own, too.

Sugar lobbyists may also push the Republican-controlled Florida Legislature to provide taxpayer funding for the project during Florida’s 2025 legislative session, which begins in March. That’s according to a slide from a power point presentation that Southland supporters provided to the South Florida Water Management District over the summer.

And even though the South Florida Water Management District has issued Southland its long-sought letter of project identification, a spokesperson for the agency said the project is not a not done deal from its perspective, either.

“Palm Beach County planning requirements require the District to review prospective project applicants before further consideration through the local process,” district spokesperson Jason Schultz said. “To that end, as the project development process continues, additional review by permitting agencies and public engagement will be required.”

Big Sugar is cynical beyond the bounds of reason. $$$

I wish you could investigate and publish corruption in every one of the states. This is appalling but I suspect will increase exponentially - and quickly - under Republican administrations. Excellent work. Be safe (bizarre that I would feel the need to say that, but so it goes…).