Records show DeSantis' Disney board chairman wanted taxpayers to spend millions on attorney fees in a Tampa tax fight

Martin Garcia, a GOP donor and the chairman of Ron DeSantis' new Disney World board, pushed state lawmakers to give more than $6 million in taxpayer money to lawyers billing up to $882 an hour.

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter and podcast devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the journalism of others — that examines the many ways that businesses influence public policy across Florida, written by Jason Garcia. Seeking Rents is free to all. But please consider a voluntary paid subscription, if you can afford one, to help support our work.

Partway through this year’s session of the Florida Legislature, the state House of Representatives rolled out an enormous package of proposed tax cuts on everything from baby diapers to cattle fencing.

“Taxpayers know how to spend their money better than the government can,” House Speaker Paul Renner, a Republican from the Jacksonville area, said at the time. “We are putting their money back in their pockets and back to work to keep our economy roaring.”

What Renner didn’t say is that he was also trying to put their money — more than $6 million of it — into the pockets of a handful of high-priced lawyers and law firms.

Buried near the bottom of the House tax package, slipped onto the second-to-last-page of a 73-page bill, was a line steering $6,214,557 to a group of lawyers who litigated against a 2018 tax increase that had been approved by voters in Hillsborough County, which includes the city of Tampa.

It was an unusual earmark, partly because courts traditionally handle decisions about attorney fees themselves. And nobody would say at the time where it came from.

But records show the multimillion-dollar payday was proposed by Martin Garcia, a Republican fundraiser in Tampa — a GOP insider best known as the person Gov. Ron DeSantis chose to lead a new state board overseeing Walt Disney World, which the governor had created as part of his feud with the Walt Disney Co.

Garcia, an attorney and investor, has been deeply involved in the five-year battle to block Hillsborough County’s transportation tax, which was approved by more than 57 percent of voters but later ruled unconstitutional by the Florida Supreme Court. Garcia personally represented the original plaintiff who challenged the tax.

In an email, Garcia said he would not receive any of the fees himself, nor would Pinehill Capital Partners, an investment firm he founded and chairs. “I have not, will not and don’t expect to receive any fees or payment/remuneration of any kind with respect to this matter — nor will Pinehill nor any other entity related to me,” he wrote.

Garcia declined to say why he urged lawmakers to pay other lawyers involved in the long-running litigation — some of whom, records show, billed at rates of nearly $900 an hour.

In a letter he sent to the House during session, Garcia said some of those other attorneys, some of whom he is personally close with, have been working on a contingency basis, meaning they expected to be paid if they won. He said “taxpayers would be getting great value” for the services those attorneys ultimately provided.

Help from the House speaker

The debate over whether to compensate the lawyers who fought Hillsborough County’s transportation tax is part of a broader battle over what to do with all the money that was collected during a roughly two-year period when the tax was in effect.

And there is a lot of it: $570 million, including interest.

DeSantis and legislative leaders failed to agree on a plan for that cash this past session, which ended last month. That means the state of Florida is still just sitting on more than half a billion dollars taken from local taxpayers in the Tampa Bay region.

Lawmakers ultimately decided not to award any attorney fees, either — at least for now.

Both fights — what to do with the $570 million and whether to give any of it to lawyers — will resume next year, when lawmakers convene their 2024 legislative session.

Transportation advocates in Tampa say lawmakers shouldn’t spend a single dime of taxpayer money rewarding expensive lawyers who litigated to undo the will of voters.

“These dollars belong to the taxpayers of Hillsborough County and were collected to fix Hillsborough County’s broken transportation system,” said Preston Rudie, a spokesperson for the organization that promoted the now-invalidated tax. “Every penny should be spent doing just that — fixing our unsafe, congested roads and enhancing transportation options.”

But Garcia has an ally in Renner, the House speaker who appears likely to continue pushing to make taxpayers pay attorney fees.

Garcia and Renner are supporters of each other. Campaign-finance records show that Garcia’s investment firm gave $25,000 to Renner in September, via one of the House speaker’s fundraising committees.

A few months later, Renner served as one of Garcia’s references when Garcia applied for his appointment to DeSantis’ Disney board, which used to be known as the Reedy Creek Improvement District and is now called the Central Florida Tourism Oversight District.

“The House’s position is that the money that was taken from taxpayers be returned to those citizens,” said Andres Malave, a spokesperson for Renner. “We will address the issue next session and hopefully arrive at a position that addresses returning money to taxpayers and addressing the possibility of attorney’s fees at the same time.”

A five-year fight in Tampa

The fight over Hillsborough County’s transportation tax has been slogging on for five years now.

Local voters approved the tax hike — which added 1 percentage point to Hillsborough County’s sales tax to finance road construction, maintenance, public transit and traffic safety — in November 2018, following a $4 million petition campaign. The top donor, according to the Tampa Bay Times, was Jeff Vinik, the owner of the Tampa Bay Lightning who is leading a $4 billion real-estate development near downtown Tampa called “Water Street Tampa.”

Critics called it a giveaway to Vinik and billionaire Bill Gates, the Microsoft founder whose investment firm is a partner in Water Street. But the tax passed easily, with 57.3 percent of the vote.

But just a few weeks later, in December 2018, a lawsuit was filed claiming the tax was illegal. The suit was brought by Stacy White, who was, at the time, a Hillsborough County commissioner who had personally opposed the tax.

In a deposition, White said that one of the first people he spoke with about suing was Garcia, a longtime Republican fundraiser whose private family foundation is a major donor to conservative organizations like The Federalist Society and Americans for Prosperity.

Garcia helped White find an attorney. Garcia also signed on to represent White himself, though Garcia never appeared in court as one of White’s attorneys.

Garcia declined to discuss his work for White. But White’s lead attorney on the case — former Florida appellate court judge Chris Altenbernd — said he included Garcia on the engagement “so that we would both have an attorney-client relationship with Mr. White.”

“That allowed Mr. Garcia to read my pleading in advance and give me a second set of eyes and ideas on the case.” Altenbernd said in an email.

Garcia and Altenbernd both agreed to represent White for free, according to the letter of retainer they signed with him.

A potentially rich class-action case

But that lawsuit was, it turned out, just the opening salvo.

About three months later, a second suit challenging the tax was filed. This suit asked the judge to make Hillsborough County refund money collected under the new transportation tax. And it was a potential class action on behalf of every taxpayer in a county of nearly 1.5 million people — so it carried the prospect of big payouts for the attorneys, if they won.

The potential-class action suit attracted an unusual legal team. The lawyers included Howard Coker, a personal injury attorney in Jacksonville. They also included partners at the Washington, D.C.-based firm Kellogg, Hansen, Todd, Figel & Frederick, whose roster of clients range from the parent corporation of Facebook to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

The team later expanded to include the big Florida firm Shutts & Bowen, led by then-Shutts partner Jason Gonzalez, a Republican attorney in Tallahassee who has advised DeSantis on the governor’s judicial appointments.

It was something of a local mystery about how such high-powered lawyers from varying practices beyond Tampa wound up in a fight over a local sales tax. “Why is a Jacksonville personal injury firm helping to challenge Hillsborough’s transportation tax?” the Tampa Bay Times asked in a March 2019 story.

Even one of the judges who presided over the class-action case joked about the strange bedfellows on a legal team that included a personal-injury lawyer and a business-defense attorney.

“I see Mr. Coker’s picture there,” Leon County Circuit Judge John Cooper said during a February 2022 video hearing. “So, Mr. Coker, you and Mr. Gonzalez are on the same side?”

“You thought you’d seen everything,” Gonzalez responded.

“It is strange, your honor,” Coker added.

Gonzalez declined to say how he became involved in the case. Neither Coker nor Derek Ho, the main Kellogg Hansen lawyer on the suit, responded to requests for comment.

Garcia also declined to say whether he helped bring any of the other attorneys into the litigation. Records show he has close connections to some of them.

For instance, Garcia and Coker are friends and have been on a fishing trip together, according to a 1998 story in the Florida Bar Journal. When Coker won a lifetime achievement award from the Florida Justice Association in 2009, Garcia presented it to him.

Meanwhile, Gonzalez — like Paul Renner, the state House speaker — served as one of Garcia’s references on his application for DeSantis’ new Disney board.

And in March, as the new chairman of the Central Florida Tourism Oversight District board of supervisors, Garcia helped award a legal contract paying up to $495 an hour to Gonzalez’s new law firm.

The Supreme Court steps in

It took a few years, but the legal challenges ultimately succeeded.

Stacy White’s original lawsuit — which was eventually merged with yet another case instigated by Hillsborough County itself — made it to the Florida Supreme Court, which ruled in February 2021 that the local transportation tax was illegal.

Why? Well, partly to reassure voters that their money would actually be spent as intended, the ballot measure included a formula spelling out where all the new tax revenue would go. For instance, it ticketed 45 percent of the funds for Hillsborough County’s mass transit agency, where it was to be spent on bus service and other public transportation.

But in its 4-1 ruling, Florida’s high court ruled that provision conflicted with a state law that says county commissioners must decide how to spend these kind of local tax dollars.

So the court killed the tax increase 26 months after it went into effect. But the justices didn’t say anything about what to do with the money that had already been collected.

That left a $570 million pot of local taxpayer money hanging in the balance — and a still-active class-action lawsuit targeting it.

How to spend half a billion

The Florida Legislature initially came up with a relatively simple solution: Spend the money on local transportation projects, just like Hillsborough County residents had voted to do.

During the 2022 legislative session — when the House and Senate were both led by representatives from the Tampa Bay region — lawmakers inserted instructions into the back of that year’s state budget.

There were a few steps involved. But eventually, the result was that local leaders in Hillsborough County would devise a list of transportation projects to fund and the Legislature would approve them during the 2023 session.

There was no mention of paying anyone’s attorney fees.

What’s more, the Legislature’s solution had the effect of the nullifying the class-action lawsuit. In January, the judge presiding over the case announced that he was going to dismiss the suit, because the Legislature had settled on a plan for the $570 million.

But then the Legislature — now led by a new House speaker and Senate president – failed to follow through.

Hillsborough County came up with a program for the $570 million, including $130 million to repave roads, $124 million to make intersections safer, and $116 million to relieve congestion. But the Legislature refused to act on it.

In fact, Rep. Stan McClain, a Republican from Ocala who sponsored the House’s tax package during the 2023 session, said House leaders never even considered spending any of the money on transportation projects.

“Was there any discussion in the possibility of reinvesting those dollars in fixing roads and things of that nature in the county?” Rep. Susan Valdes, a Democrat from Tampa, asking during a committee hearing on the legislation.

“That was not contemplated by us,” McClain responded.

Two new plans — with millions in fees

Instead, two different ideas emerged.

The first was proposed by Gov. Ron DeSantis, who called on the Legislature to set up a refund system for Hillsborough County taxpayers — just like the attorneys in the class-action suit wanted to do. The governor also wanted any leftover money that went unclaimed to be spent on local transportation projects.

There are two big problems with this approach. First, it would likely only benefit a handful of big businesses. They are the taxpayers most likely to have years-old receipts documenting their sales tax payments — and expenses big enough to make it worth pursuing a 1 percent refund.

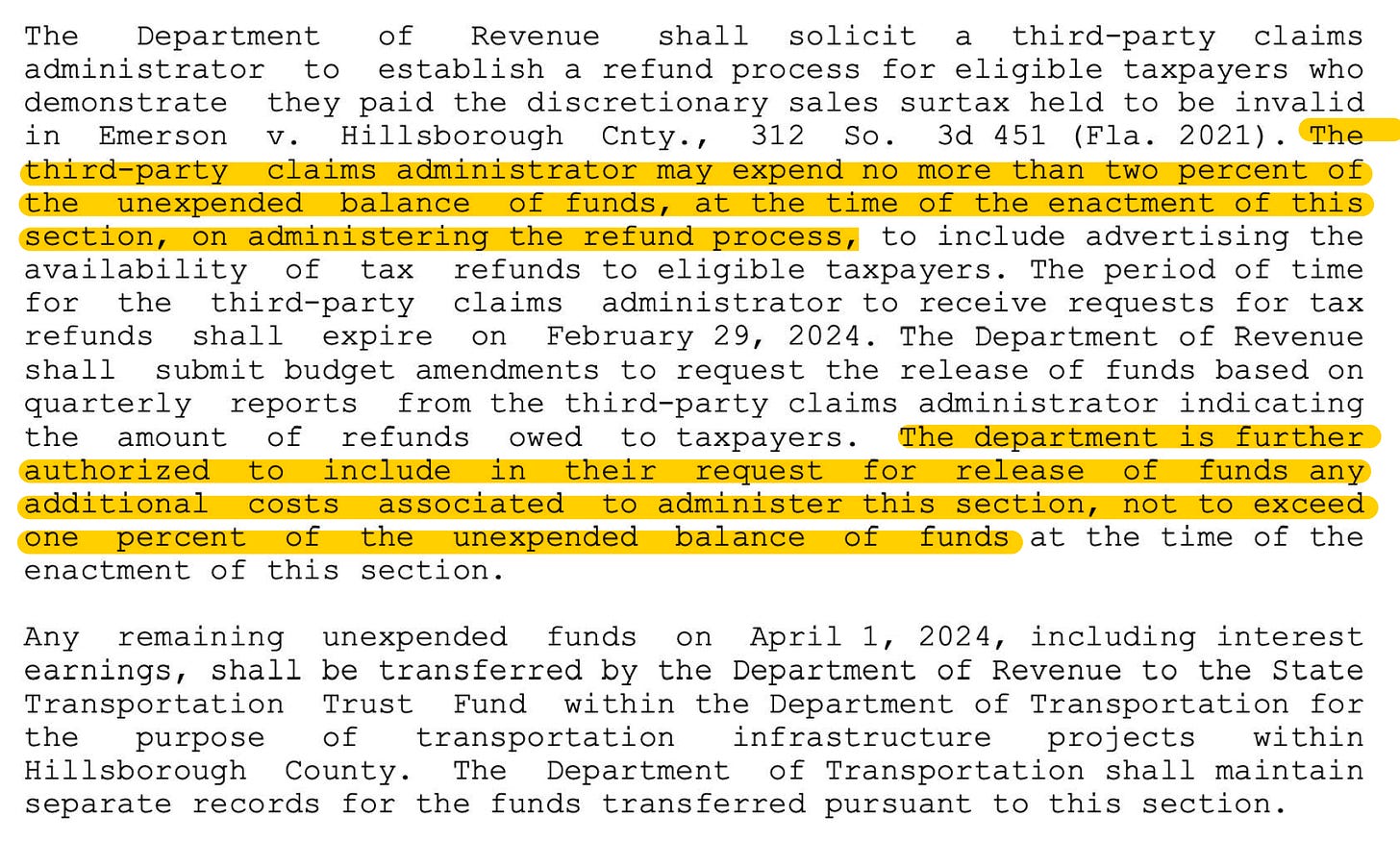

Second, a refund scheme would waste a lot of taxpayer money on overhead. DeSantis’ own proposal called for spending up to 3 percent of the $570 million — more than $17 million — on a vendor hired to administer a refund-claims process, plus “any additional costs.”

The Florida House of Representatives, under House Speaker Paul Renner, hatched a different plan. The House chamber proposed what would essentially have been a giant tax holiday in Hillsborough County. It would have worked by suspending other county sales taxes and using the $570 million to offset the revenue loss to the local governments.

The House plan had the advantage of minimizing overhead costs for taxpayers.

But then the House paired it with the $6,214,557 earmark for attorney fees.

Lawyers billing $882 an hour

Records show that figure came directly from Martin Garcia, who wrote a letter to the House in the middle of session recommending that they pay $6,214,556.44 to the three law firms involved in the class-action litigation — even though the judge had already announced he was going to dismiss that suit.

According to Garcia’s letter, that amount would have paid the firms for five times their fees, which he said were based on more than 1,800 hours of work.

Had lawmakers ultimately approved the payments, Kellogg Hansen, which billed at an average rate of $591 an hour, would likely have received more than $3.3 million. Coker Law, which billed at $805 an hour, would likely have been paid nearly $1.9 million. And Shutts & Bowen, which billed $882 an hour, would have pocketed about $1.1 million.

“In short, the taxpayers would be getting great value for the services provided relative to their recovery of $570 million — not even taking into account the billions in future surtax revenues that will never be wrongfully collected now that the charter amendment has been invalidated,” Garcia wrote.

It's not clear if any of these firms advocated for these fees themselves.

During a very brief public discussion of the issue, Rep. Stan McClain — the Ocala Republican who sponsored the House tax package — misleadingly implied that lawmakers were required to pay these attorney fees.

“We needed to set an amount aside to make sure all that stuff was paid, separate from the sales-tax relief,” McClain said.

Only the Florida Senate prevented it from happening. Near the very end of session, after the House and Senate failed to agree on a plan for the full $570 million, the Senate made sure to pull an attorney fee provision out of the tax package, too.

“I believe, as I think probably everyone here would, it’s best attorneys don’t get paid before taxpayers get their refunds,” Sen. Jim Boyd, a Republican from Bradenton, said on the Senate floor.

I would like to know what DeSantis & money grabbing buddies did with those emergency funds the State received for that last storm that caused pretty much catastrophic floods?

He has cut off people from receiving help

This is so disturbing and the situation feels so hopeless. What can be done to stop this madness?