Records show how Ron DeSantis targets his attacks on free speech — despite what his lawyers claim in court

A look at how the governor of Florida and Republican presidential candidate tries to sidestep the U.S. Constitution in order to silence speech he dislikes.

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter and podcast devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the journalism of others — that examines the many ways that businesses influence public policy across Florida, written by Jason Garcia. Seeking Rents is free to all. But please consider a voluntary paid subscription, if you can afford one, to help support our work.

It was the fall of 2021, and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis was already losing his much-ballyhooed battle against “Big Tech oligarchs.”

DeSantis had recently pushed a new law through the Florida Legislature meant to punish social-media platforms that refuse to publish posts by certain political figures or news organizations — even if those posts violate the companies’ rules on things like hate speech, violent incitements, or disinformation.

In public statements, DeSantis and his allies boasted about standing up to the big social-media companies that they said were censoring conservative voices — like the companies behind Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Snapchat, all of which had suspended or banned former President Donald Trump after his posts helped incite an attack on the U.S. Capitol following the 2020 presidential election.

But the governor and lawmakers had been much craftier when drafting the legislation itself. They wrote a very broad law that potentially covered a wide range of companies doing business online, which allowed attorneys for the state to claim in court that the law did not unconstitutionally target a few specific actors that DeSantis did not like.

That had, however, caused its own problems. When a pair of trade groups representing the tech industry sued to stop the law, the judge presiding over the case noted that Florida’s effort to stop alleged censorship on social media was so vague that it could also prevent a company like Home Depot from moderating the comments on its own website. The judge blocked the law from taking effect, ruling that it likely infringed on freedom-of-speech rights protected by the First Amendment.

The state of Florida had appealed. But the high-priced attorneys hired to defend the new law wanted to strengthen their case. So, in October 2021, they suggested some improvements to DeSantis’ staff.

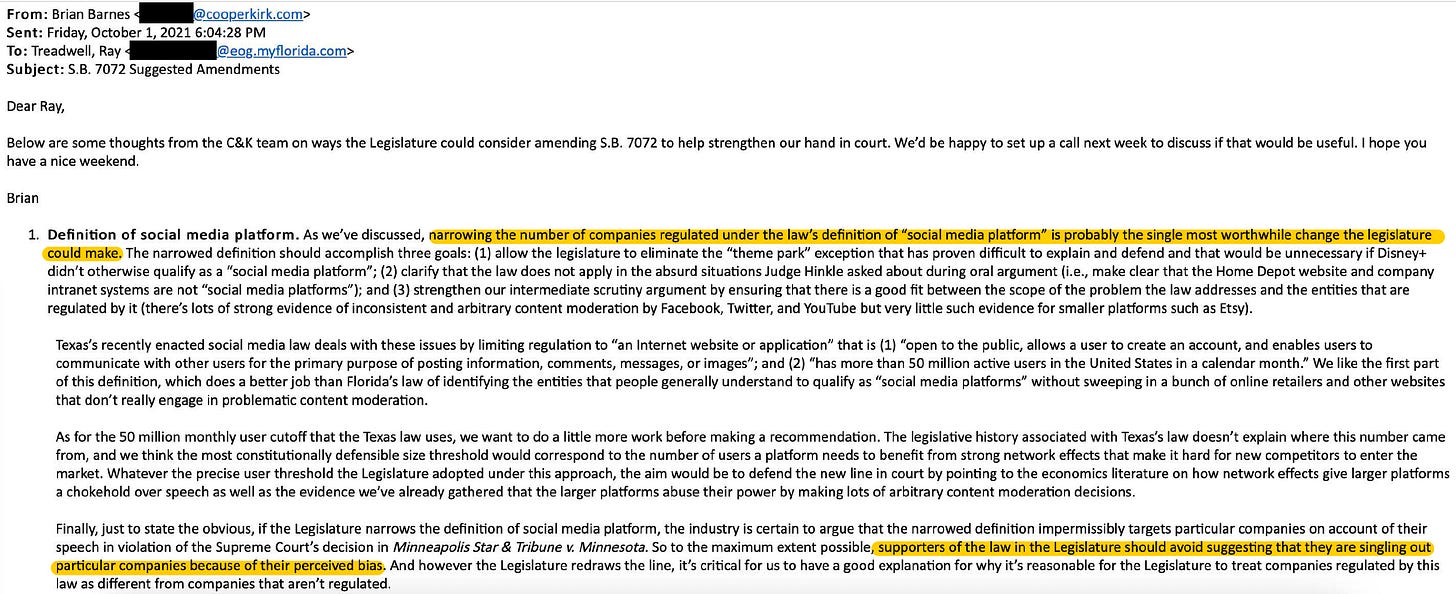

“As we’ve discussed, narrowing the number of companies regulated under the law’s definition of ‘social media platform’ is probably the single most worthwhile change the legislature could make,” Brian Barnes, an attorney at the Washington, D.C.-based firm Cooper & Kirk wrote in an Oct. 1, 2021, email to an attorney in the Governor’s Office.

But then Barnes added a word of warning.

“Finally, just to state the obvious, if the Legislature narrows the definition of social media platform, the industry is certain to argue that the narrowed definition impermissibly targets particular companies on account of their speech,” Barnes wrote.

“So to the maximum extent possible, supporters of the law in the Legislature should avoid suggesting that they are singling out particular companies because of their perceived bias,” Barnes added. “And however the Legislature redraws the line, it’s critical for us to have a good explanation for why it’s reasonable for the Legislature to treat companies regulated by this law as different from companies that aren’t regulated.”

DeSantis staff listened. Separate records show that, a few months later, the Governor’s Office proposed a new bill to the Florida Legislature that would have made many of the changes to the social-media law that Cooper & Kirk had suggested.

But in the process of drafting that legislation, DeSantis’ aides also made it crystal clear exactly who DeSantis had been trying to target all along.

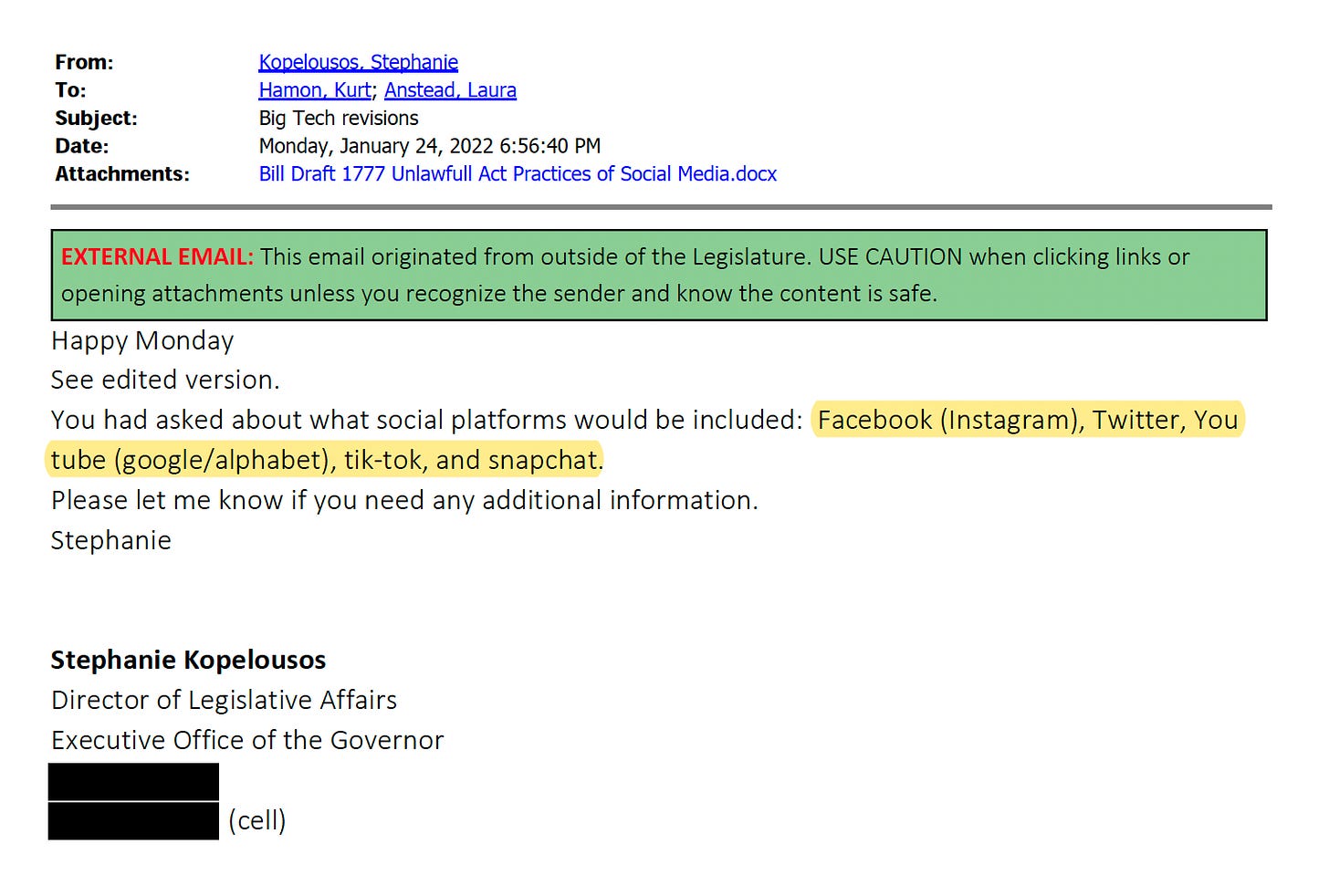

It happened after staffers in the Florida House of Representatives apparently asked the Governor’s Office to explain what companies would still be covered by the narrower definition of social-media platform that DeSantis wanted lawmakers to enact.

“You had asked about what social platforms would be included: Facebook (Instagram), Twitter, Youtube (google/alphabet), tik-tok and snapchat,” DeSantis’ then-director of legislative affairs wrote in a Jan. 24, 2022, email to a pair of House staffers who had worked on the original social-media legislation.

DeSantis’ attempt to tighten up his social-media law didn’t pass. So the original law — which Florida will soon attempt to defend before the United States Supreme Court — remains largely untouched today (with one notable exception, which we’ll get to in just a bit).

But the episode confirms the true intent behind one of DeSantis’ signature pieces of legislation — and the lengths his administration will go to hide that intent.

It’s also part of a well-established pattern for DeSantis, the Republican presidential candidate who has spent much of his time as Florida’s chief executive searching for ways to sidestep the U.S. Constitution in order to silence speech he dislikes.

A more recent example involves an anti-LGBTQ+ law DeSantis and the Florida Legislature approved earlier this year that is designed to prevent people from performing in drag in front of anyone under the age of 18.

Just as they had with their social-media law, DeSantis and his supporters in the Legislature loudly and proudly boasted about shutting down drag shows while actually writing a far more circumspect piece of legislation. The result was a foggy law forbidding vaguely defined “adult live performances” — which lawyers for the state insisted was about more than attacking just one kind of art form that happens to make a few Florida politicians uncomfortable.

But once again, records later revealed that DeSantis and lawmakers really were just chasing after drag queens. Federal courts have blocked that law from taking effect, too.

This has also been a central strategy in DeSantis’ efforts to punish the Walt Disney Co. for speaking out against a different anti-LGBTQ+ law and for suspending its campaign contributions in Florida.

DeSantis has, among other things, persuaded the Legislature to pass one law threatening to dissolve the formerly-Disney-controlled municipal government that oversees Walt Disney World and another law that give him control of that district instead.

Disney responded by suing the governor and some of his appointees, accusing the state of unconstitutionally retaliating against the company simply for engaging in protected political speech. But lawyers for the governor’s appointees have claimed in court that none of these laws technically single out Disney alone.

But public records suggest DeSantis has, in fact, been searching ways to target Disney exclusively.

Disney is especially interesting in the context of DeSantis’ social-media law, which was passed back when the governor and the company had a much warmer relationship with each other.

In fact, just before that social-media law passed, Disney grew alarmed that it, too, would be swept up by the broad wording of the legislation. So company lobbyists reached out to DeSantis — to whom they had recently given $50,000. And DeSantis’ aides leapt into action, helping the company get a last-minute — and utterly incoherent — carveout from the law.

DeSantis helped Disney get that carveout even though doing so made his social-media law far more vulnerable to a constitutional challenge.

In fact, in that Oct. 1, 2021, email from Cooper & Kirk partner Brian Barnes to one of DeSantis’ in-house attorneys, Barnes specifically urged the governor’s office to remove Disney’s exemption because it had proven “difficult to explain and defend.” (In an ironic twist, this email surfaced as part of the current litigation between Disney and DeSantis.)

DeSantis finally ordered the Legislature to get rid of Disney’s exemption in April 2022 — but only after Disney had stopped giving him campaign contributions and DeSantis decided that the company was now more useful as culture-war cannon fodder.

But even revoking Disney’s carveout has caused complications. Becuase attorneys for the tech groups that are challenging the social-media law are now citing that reversal as yet more evidence of Ron DeSantis’ history of using state power to suppress disfavored speech.

In a brief filed last month with the U.S. Supreme Court, lawyers for the tech trade groups — NetChoice and the Computer & Communications Industry Association — pointed out that DeSantis and the Florida Legislature were happy to give Disney a “gerrymandered carve-out” from the social-media law until Disney angered them by speaking out on another issue.

“The state later discovered,” they wrote, “that the viewpoints it wished to punish are not limited to Silicon Valley, but reach Hollywood, too.”