Ron DeSantis has a plan to protect...tax evaders?

More from the DeSantis Drafts: Florida’s governor wrote a bill that could have blocked other states from collecting income taxes owed by billionaires who buy homes in Florida

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter and podcast devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the journalism of others — that examines the many ways that businesses influence public policy across Florida, written by Jason Garcia. Seeking Rents is free to all. But please consider a voluntary paid subscription, if you can afford it, to help support our work.

There’s been quite a bit written in recent weeks about some of the ideas Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis was working on behind the scenes in the weeks leading up to this year’s legislative session.

The governor’s ideas included unsuccessful proposals to strip public universities of autonomy and to expand executive power while weakening independent institutions — and one quite successful proposal to force Floridians to wait six months for a gas-tax break until it was most politically advantageous to DeSantis’ re-election campaign.

But maybe the most bizarre piece of legislation that the governor’s office drafted before session was this one: A bill attempting to interfere with efforts by other states to collect taxes.

The proposal sought to stop employees of other states from auditing or collecting unpaid personal income taxes from people who live — or who merely own a second (or third or fourth) home — in Florida, unless they first obtained licenses as “out-of-state tax collectors.”

And those licenses would have been expensive: $25,000 to apply; $50,000 for the license itself and for every year it is renewed; and $75,000 for each physical office in the state. (It’s not uncommon for a state to have tax offices in other states; the Florida Department of Revenue has employees in eight other states around the country). It’s possible that attorneys or debt collectors hired by another state would have had to get licensed, too.

The bill would have required tax collectors from other states to abide by some of Florida’s tax-collection laws — even if Florida’s laws conflicted with the laws of their own state. And it threatened felony criminal penalties against anyone who failed to comply.

Like DeSantis’ proposals to prevent university presidents from hiring their own faculty, make it harder to pull public records out of his administration and undercut citizen-led constitutional amendment campaigns, this out-of-state income tax collection idea ultimately went nowhere during the Florida Legislature’s 2022 session, which ended in March.

The governor’s office declined to answer questions about the proposal. But it may have been inspired by legal conflicts that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many companies moved white-collar employees to remote work — raising questions about where taxes were owed by huge numbers of employees suddenly working from a home in one state for a business in another.

The state of New Hampshire — which, like Florida, does not have a personal income tax (though New Hampshire does tax interest and dividend income) — even sued the state of Massachusetts over the issue. The lawsuit failed, but some of the central legal questions remain unresolved.

Now, it’s not clear whether this was really intended to be serious policy or merely a messaging bill that DeSantis could campaign on: Under audit in New York? Flee to the free state of Florida!

But it’s worth remembering that DeSantis, who is up for re-election this fall and is widely expected to run for president in 2024, is currently raising enormous sums of money from millionaires and billionaires. A fascinating recent story by Zac Anderson, the political editor of the Sarasota Herald-Tribune, found that 42 billionaires have given DeSantis a combined $12.5 million – more than $1 of every $10 the Republican governor had raised.

The ultra-rich are, of course, the people who would most likely benefit if Florida were to seriously try to thwart income-tax audits and collection efforts by other states. It probably wouldn’t be difficult for a hedge-fund manager in New York or a tech-company founder in California, who may have engaged in some aggressive tax-sheltering strategies and is now facing an audit, to buy a home in Florida.

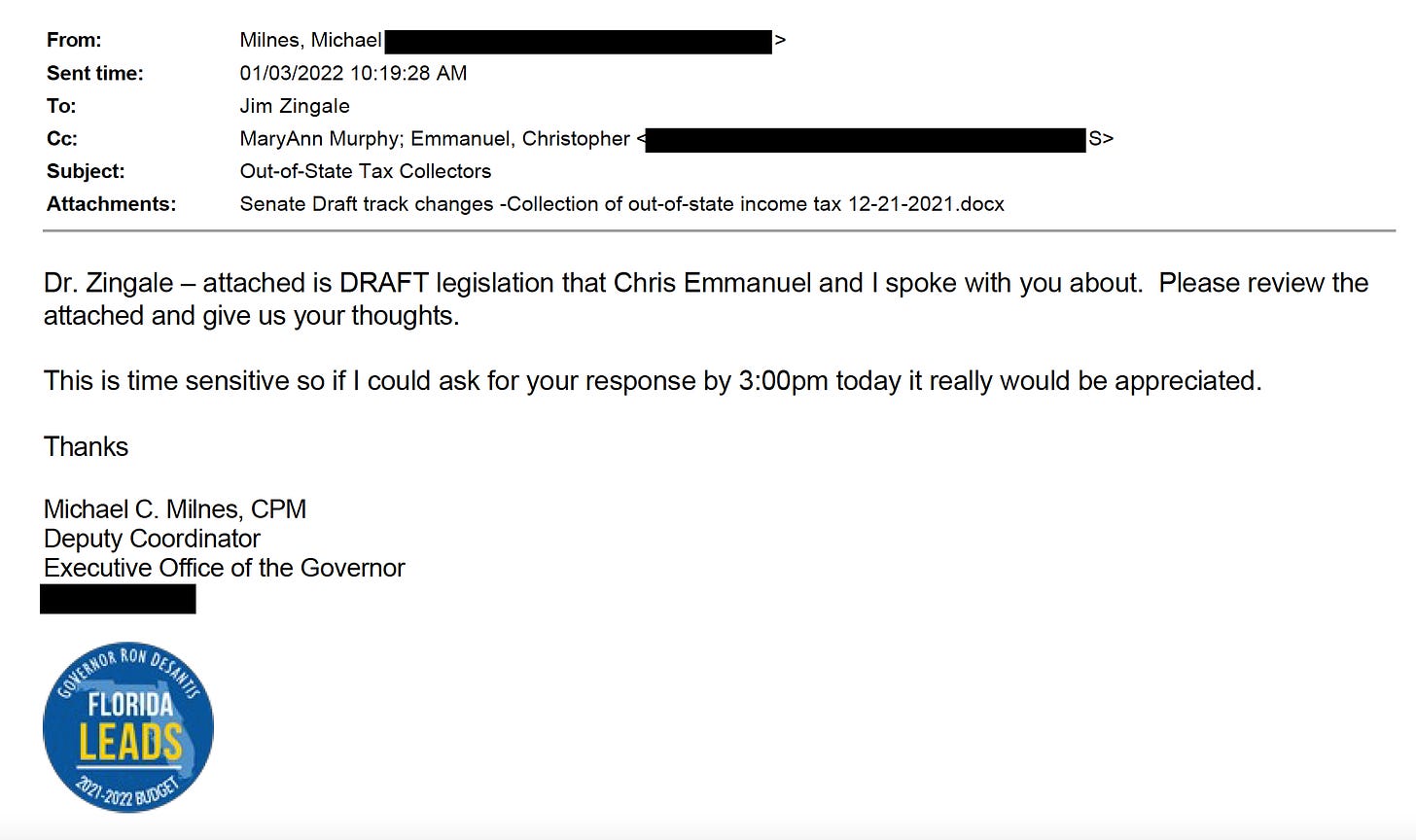

Emails show DeSantis’ staff took this idea seriously enough that they asked the executive director of the Florida Department of Revenue to provide feedback on it.

The revenue department had some concerns.

“It is possible that the proposal could result in retaliatory actions by other states,” the agency wrote in an analysis of DeSantis’ proposal. “Florida, like all states, takes such action necessary to assess and collect taxes owed to the state, regardless of where the individual lives or business is domiciled. In doing so, state revenue agencies are subject to laws of the state regarding enforcing the collection of debts.”

Separately, I showed this legislation to half a dozen tax-law experts, both in Florida and around the country, after it surfaced in a public-records request seeking communications between the governor’s office and the Legislature during session. Every one of those experts agreed that, had the bill passed, it would likely have been ruled unconstitutional.

“It would seem to be pretty clearly a violation of at least three different Constitutional clauses,” said Darien Shanske, a law professor at the University of California, Davis. “One way of looking at it is, when you sign a contract in Florida, you don’t think to yourself, ‘If this goes south, I’m just going to move to Georgia and they’re never going to get me.’”

Then again, that’s not necessarily a deterrent to DeSantis — a governor who has already racked up more than $5 million in legal bills while paying favored lawyers up to $725 an hour to defend constitutionally questionable laws. (Which we know thanks to Skyler Swisher of the Orlando Sentinel, who used the state’s public-records laws to obtain copies of the governor’s legal contracts.)