Ron DeSantis worried Wilton Simpson’s prized bill would protect puppy mills. Will he veto it?

DeSantis tried to get Simpson to change the “Local Business Protection Act." But Simpson, who has raised more than $100K from a company that sells puppies for profit, wouldn't do it.

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the journalism of others — that examines the many ways that businesses influence public policy across Florida, written by Jason Garcia.

One of Senate President Wilton Simpson’s top priorities this past session was a piece of legislation dubbed the “Local Business Protection Act” — a bill that would allow businesses to sue cities or counties that pass local laws that cut into their profits.

Among those most alarmed by Simpson’s far-reaching legislation are animal-welfare activists, who fear it will torpedo efforts to shut down puppy mills by getting local governments to pass laws prohibiting the sale of cats and dogs in pet stores.

Most major pet retailers have long since stopped selling puppies for profit. But there is one that still does: Petland, the nation’s No. 9 pet-store chain, with around a dozen locations across Florida. If Simpson’s bill becomes law, Petland could sue a city that tries to ban dog sales — and force the city to pay Petland up to seven years’ worth of lost profits.

Someone else apparently shares this concern: Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis.

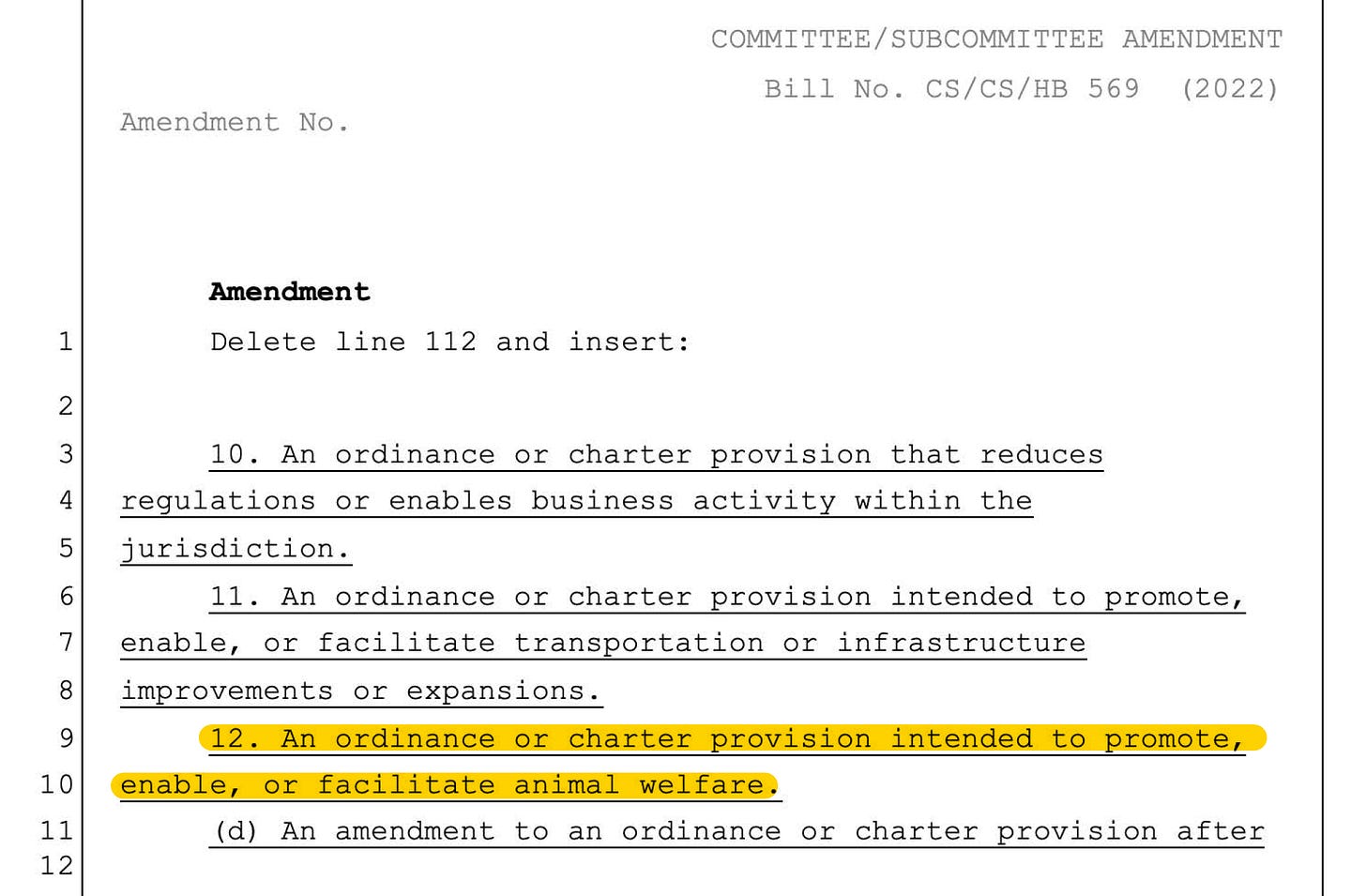

Emails obtained through a public records request show that a top DeSantis aide reached out to Simpson’s chief of staff late in the legislative session to express concerns that Simpson’s prized piece of legislation would become a legal shield for puppy mills. The governor’s office asked the president’s office to amend Simpson’s bill (SB 620) to ensure that local governments wouldn’t face retaliation for laws meant to protect animals.

“A local ordinance regulating puppy mills would expose the local government to legal action by the puppy mills,” according to a memo sent by DeSantis’ legislative affairs director to Simpson’s chief of staff on Feb. 23.

Simpson, who records show has raised more than $125,000 from Petland and its franchisees, declined to change his bill. The Legislature passed SB 620 two weeks later without any exemption for animal-welfare ordinances.

But now the ball is in the governor’s court.

DeSantis has yet to sign Simpson’s bill. And animal-welfare groups are urging him to veto it.

Money and lobbying muscle

As animal-rights groups have fought to eliminate puppy mills — high-volume breeding facilities in which dogs are born into often-inhumane conditions — they have focused on choking off what they call the “puppy mill-to-pet store pipeline.”

They have had lots of success: In Florida alone, 13 counties and 70 cities have enacted local ordinances strictly regulating or banning retail puppy sales, according to the Humane Society of the United States.

No one has more to lose from this effort than Chillicothe, Ohio-based franchisor Petland, which has approximately 150 stores in multiple countries. While other major pet-store chains work with local rescue groups to promote adoption of lost or abandoned dogs, Petland has leaned in as the last chain still selling dogs itself.

“While other pet stores shy away from finding homes for pets, at Petland we are proud of our 55-year history of matching the right pet with the right customer,” Petland CEO Joe Watson told Pet Business earlier this year. (Petland’s dogs can cost thousands of dollars each; luckily, the company also offers financing with a Petland credit card and a 30 percent interest rate.)

Petland has fought back hard against the efforts to ban puppy sales. In Florida, the company has been lobbying for at least three years to pass a law that would strip cities and counties of the power to regulate dog sales.

This year’s attempt was HB 849 and SB 994, which supporters tried branding as the “Florida Pet Protection Act” but which emails show was written at least in part by lobbyists for Petland. The same emails show that Petland lobbyists provided talking points that Sen. Manny Diaz, R-Hialeah, used when presenting the bill.

As part of this effort, the company has also become a substantial donor to political campaigns: Records show that Petland and its franchisees have made more than $680,000 in Florida campaign contributions over the past five years. That includes $125,000 to a fund controlled by Simpson and other Senate Republican leaders, plus $48,500 to Simpson himself and his personal political committees. (Simpson, a Republican from Pasco County, is now running for election as Florida’s commissioner of agriculture — the office responsible for enforcing Florida’s statewide pet law.)

Petland also appears to have become a donor to other groups, too: This year, for instance, the big-business front group Associated Industries of Florida’s decided that one of its top legislative priorities was to stop “activists...working to shut down long-standing local businesses that provide Florida families with safe and healthy pets.” (Petland has faced complaints of selling sick puppies.)

Still, for all its money and lobbying muscle, Petland has struggled to gain traction in Tallahassee, where the welfare of pets is one of those emotional issues that crosses party lines and can trump even campaign contributions. The company’s legislation only made it through a single committee in the Senate this year — and none at all in the House.

Wilton Simpson to the rescue

But Wilton Simpson offered Petland another way to solve its problem.

SB 620 wouldn’t undo any dog-sale bans that are already in place. But opponents say it will deter other cities and counties from enacting similar bans.

That’s because under the legislation, any business (regardless of how big it is or where it’s headquartered) that projects a loss of at least 15 percent of its profits at one or more locations due to a new local ordinance or charter amendment — like a pet store that sells puppies at thousands of dollars a pop and 30 percent financing that can no longer sell puppies — can sue the local government for damages. If the suit is successful, the local government would have to pay the business up to seven years of lost profits.

It's not clear if Petland lobbied Simpson on the Local Business Protection Act. But the company’s lobbyists registered to lobby on the legislation, according to disclosure records filed in the state House. And there was obviously behind-the-scenes resistance to the effort to exempt animal-welfare ordinances from the legislation.

It wasn’t just Simpson rejecting DeSantis’ amendment. Democrats in the Florida House also tried to protect local animal-welfare laws by forcing a vote on a similar amendment just before SB 620 was passed for good.

But Rep. Lawrence McClure, a Republican from near Tampa who sponsored the legislation in the House, urged House members to vote against it — though he sounded reluctant to do so. “This amendment is unfriendly, sadly,” McClure said.

The amendment failed on a 69-46 vote, with four Republicans joining Democrats in support of it.

After session, Petland wrote a $10,000 check to McClure’s political committee.

It all comes down to DeSantis

Katie Betta, a spokesperson for Simpson, said Simpson and the Senate did not take up the governor’s amendment to SB 620 because they felt like they had already addressed DeSantis’ concerns.

For instance, Betta noted that, in order to sue a local government under SB 620, a company must be engaged in a legal line of business. It must have been in operation in the jurisdiction for at least three years before the offending ordinance is passed. It must forecast a reduction of at least 15 percent of its profits. And SB 620 wouldn’t affect any existing animal-welfare laws (though it could complicate any future efforts to change or strengthen them.)

“In our view, the combination of these provisions addresses the concerns raised,” Betta said.

Animal-rights groups clearly disagree. Shortly after session, the Humane Society of the United States launched a campaign encouraging people to contact the governor’s office pleading for a veto. The group also aired a television commercial on Fox News in Tallahassee, trying to catch DeSantis’ attention.

“Special interests are trying to change Florida law to protect puppy-mill cruelty,” a narrator says in the spot, amid images of caged, sick and dead puppies. “Urge Governor DeSantis to protect pets and consumers and veto Senate Bill 620.”

Ultimately, of course, it all comes down to DeSantis.

It’s worth noting that Petland franchisees gave $25,000 to DeSantis during his Republican primary race against former Florida Agriculture Commissioner Adam Putnam (though it did so after Donald Trump put DeSantis in the driver’s seat in that race). DeSantis also recently chose one of Petland’s biggest champions in the Legislature — Sen. Manny Diaz — to be the state’s new secretary of education.

But DeSantis also shown he is plenty willing to buck campaign contributors when he senses political danger. The most striking example of that came last week when he vetoed anti-rooftop-solar legislation that was initially written by lobbyists for Florida Power & Light — the utility giant whose consultants were deeply involved in one of the biggest election scandals in recent Florida history (a scandal, by the way, that directly benefitted Wilton Simpson by giving him a more workable majority as Senate president.)