Secrecy, strategy and spin: Inside the Ron DeSantis decision to suspend a prosecutor who promised to protect abortion

Internal records and sworn testimony reveal how — and why — Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis removed an independently elected prosecutor in Tampa who had pledged not to prosecute women seeking abortions.

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter and podcast devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the journalism of others — that examines the many ways that businesses influence public policy across Florida, written by Jason Garcia. Seeking Rents is free to all. But please consider a voluntary paid subscription, if you can afford it, to help support our work.

A little after 9 p.m. on June 30, Ryan Newman, the general counsel to Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, forwarded an email to Larry Keefe, a former Donald Trump appointee who now works in the DeSantis administration as the governor’s “public safety czar.”

The email linked to a joint statement signed by more than 90 elected prosecutors around the country, in which they collectively pledged not to prosecute women seeking abortions or their doctors in the aftermath of a U.S. Supreme Court decision allowing states to make abortion illegal. The prosecutors who signed onto the statement included one from Florida: Andrew Warren, the state attorney in Hillsborough County, which includes the city of Tampa.

Keefe responded to Newman 30 minutes later. “Ready to engage,” he wrote.

Though few people knew it yet, records show that the Republican governor’s office had been quietly targeting Warren for months, trying to build a case to take down an outspoken liberal prosecutor who was becoming one of the highest-profile elected Democrats in Florida. Warren’s abortion pledge, DeSantis and his aides quickly concluded, gave them the ammunition they needed.

Exactly five weeks later, DeSantis suspended Warren and had him forcibly removed from his office by an armed police officer. It was a muscular flex of executive power that drew gushing coverage from conservative media for a governor who has spent four years trying building a national profile ahead of a potential 2024 presidential campaign.

DeSantis’ team gleefully fanned the flames. “Prepare for the liberal media meltdown of the year,” Christina Pushaw, DeSantis’ then-press secretary, teased on Twitter at 9:32 p.m. the night before DeSantis announced the suspension.

But then Warren did something that surprised DeSantis. The governor’s office had expected the state attorney might file a lawsuit in state court challenging DeSantis’ authority to suspend him. But Warren took the governor to federal court instead, accusing DeSantis of unconstitutionally punishing a critic and potential political rival who had exercised his right to free speech.

The trial starts Tuesday. But the litigation has already forced a governor’s office that is notoriously slow to comply with public-records requests to turn over a cache of internal documents — including emails, text messages, media plans and strategy memos. It has also compelled several of DeSantis’ closest aides to testify under oath.

Taken together, the records and testimony reveal a glimpse into the inner workings of the DeSantis administration — from the steps that DeSantis and his staff take to maintain secrecy to the raw political calculus that guides the governor’s decision-making.

They also show that DeSantis at times misled the public about key aspects of the Warren suspension. The governor exaggerated the amount of investigative research his staff did in advance of the move. And he ordered aides to downplay the role that Warren’s abortion pledge played in his decision.

A statewide review — or an informal look?

DeSantis suspended Warren on Aug. 4. But the seeds were planted at least eight months earlier, in December 2021, during a meeting in the governor’s office between DeSantis and two top aides: Chief of Staff James Uthmeier and Keefe, a former law partner of Republican U.S. Rep. Matt Gaetz and Trump-appointed federal prosecutor whom DeSantis hired in September 2021 as his “public safety czar.”

It's not clear what the meeting was about. But in the middle of it, DeSantis suddenly asked his aides, unprompted, whether any state attorneys in Florida were “not enforcing the law,” according to an excerpt from a deposition of Keefe.

“At some point in that meeting, the Governor asked me whether any of the state attorneys in Florida were not enforcing the law, and I responded that I did not know but that I would be glad to look into it,” said Keefe, who is probably best known for coordinating the stunt in which DeSantis had nearly 50, mostly Venezuelan migrants rounded up in Texas and flown to Martha’s Vineyard, where they were dropped off without any notice to local officials.

“The Governor said nothing further on that, and we went back to the discussion that we were having on other subjects,” Keefe said. The entire exchange, he added, took less than 30 seconds.

But while the exchange may have been quick and casual, Florida’s Republican governor appears to have been hungry for a fight with a Democratic state attorney somewhere in the state — particularly someone like Warren, an outspoken progressive who had been elected with help from billionaire Democratic donor George Soros and who was gaining a national reputation as a criminal-justice reformer who would not seek to imprison people for low-level, non-violent offenses or keep them locked up in jail simply because they can’t afford the cash bail.

Separate records obtained from the Florida Legislature show DeSantis’ staff wrote a bill before last year’s legislative session that would have given DeSantis more explicit authority to suspend a state attorney like Warren.

The state Constitution allows the governor to suspend local elected officials for offenses such as “neglect of duty” or “incompetence.” But those terms are only vaguely defined in law.

The bill that DeSantis’ office wrote would have made it crystal clear that any state attorney who adopts a “blanket policy” to not prosecute certain categories of offenses would be neglecting their duty — and therefore subject to suspension by the governor. The legislation failed to pass.

DeSantis also included a warning to all 20 state attorneys across Florida in his annual State of the State address to the Florida Legislature in January 2022. “We will not allow law enforcement to be defunded, bail to be eliminated, criminals to be prematurely released from prison, or prosecutors to ignore the law," DeSantis vowed.

Sometime after that 30-second exchange with the governor, Keefe began to reach out to friends in Florida law enforcement to see if anyone had any complaints about their local state attorney, according to Keefe’s deposition.

DeSantis would later publicly claim that his office had performed a thorough review of every state attorney in Florida before he decided to suspend Andrew Warren. “This was a statewide review to make sure that we were not going down the road of San Francisco, Los Angeles,” he said at a press conference announcing the suspension. “I asked staff to review all state attorneys in the state of Florida,” DeSantis added in an interview later that night with Fox News host Tucker Carlson.

But under oath, Keefe described a far more informal and sporadic survey.

“Was there, at the Governor’s request, an investigation or review of state attorneys offices across Florida?” an attorney for Warren asked Keefe during a deposition.

“My recollection of that was not that the Governor requested anything,” Keefe responded. Keefe said he decided himself to take on the task of spot-checking with various police officers and prosecutors.

“It was not a systematic, methodical investigation,” Keefe said. “No one was guiding or directing or telling me what to do. There was no timeline. There was no sense of urgency. It was information I was collecting on an ad hoc basis in the general course of doing my work.”

Keefe said he never spoke to Warren or any other attorneys in Warren’s office. And Ray Treadwell, DeSantis’ chief deputy general counsel, said in a separate deposition that he didn’t think that Keefe or anyone else ever wrote any kind of report summarizing the findings of Keefe’s surveys.

It’s not clear from the court records whether the governor’s staff scrutinized any state attorneys other than Warren. But if Warren wasn’t their target right from the start, he became their sole focus very soon.

“All roads led to Mr. Warren based on that informal ‘look into’ survey that I did,” Keefe said.

Avoiding an electronic trail

A few months after beginning his “informal ‘look into’ survey,” Keefe decided to seek help from Chad Chronister, the Republican sheriff in Hillsborough County. But Keefe didn’t contact Chronister directly.

Instead, according to a deposition of Chronister, Keefe approached him through an intermediary: Preston Farrior, a Tampa businessman. Farrior is the son of a wealthy Coca-Cola investor and an in-law in the family behind Ferman Automotive Group, which owns car dealerships in Tampa. The Farrior and Ferman families are both substantial campaign contributors — including to both DeSantis and Chronister.

In his deposition, Chronister said he met Farrior for lunch in March or April at Caso Santo Stefano, a Sicilian restaurant in Ybor City. Near the end of the lunch, Chronister said, Farrior asked the sheriff if he would be willing to “jump on a quick call” with Larry Keefe from Ron DeSantis’ office.

Chronister said he didn’t know who Keefe was but agreed to do it. So he and Farrior walked to Farrior’s car, got inside, and Farrior called Keefe on speakerphone. That’s when Keefe then told Chronister what he was after.

“He said he was tasked by the governor to review all the state attorneys to determine which ones weren’t prosecuting cases, and his investigation kept leading him back to our state attorney,” Chronister said. “He asked me if we had any difficulties getting cases prosecuted here. I indicated that we did. Indicated that we had already started compiling a list of cases, and I’d directed our staff to start keeping track of these cases that weren’t being prosecuted.”

It's not clear why Keefe didn’t call Chronister directly. Chronister said he didn’t know. Keefe did not respond to a request for comment. Farrior could not be reached for comment.

Keefe began to work with Chronister directly at this point. But he took steps to keep their communications hidden. For instance, Chronister said Keefe asked the sheriff to download and use Signal, an encrypted text-messaging and phone app.

“Did he tell you why?” an attorney for Warren asked Chronister.

“Because it’s encrypted,” Chronister replied. “Either receiving or sending it, nobody would see what we were talking about. It would stay encrypted.”

Using Signal, Keefe asked Chronister to send him records related to the cases that Warren hadn’t prosecuted. But rather than have digital files emailed, Chronister said Keefe asked to have paper copies sent to Tallahassee by FedEx.

And later, when Chronister wanted to email something to Keefe, Chronister said Keefe instructed him to use Keefe’s personal email address rather than his state account.

“Did you think it was weird that, like, a senior member of the governor’s office was Gmail-ing you about official business?” Warren’s attorney asked.

“No. I wouldn’t think it was weird,” Chronister answered. “To be honest with you, I didn’t pay enough attention to it to even think about it.”

The public-safety czar isn’t the only one in the Governor’s Office who seems to avoid creating traceable trails of electronic communications.

During a separate deposition, Christina Pushaw, the former DeSantis press secretary who later went to work for the governor’s re-election campaign, said she was not aware of any staffer who texts or emails with the governor himself.

“Is it your understanding that the only way people communicate with the governor is in person or perhaps via telephone?” an attorney for Warren asked.

“That is my understanding,” Pushaw said, according to an excerpt of the deposition.

Struggling to build a case

By June, DeSantis’ office had compiled of list of cases Warren hadn’t prosecuted and policies he’d implemented that they didn’t like.

Among them: Warren’s office generally declined to prosecute homeless people found sleeping on a business’ private property or people arrested while riding a bicycle whose only offense was non-violently resisting arrest. Civil-rights activists have accused police officers in Tampa of using such bike stops to target people of color, sometimes referring to the resulting charge as “biking while Black.”

But all of the decisions could reasonably be explained as Warren and his staff simply exercising their legal discretion as prosecutors to decide which cases to pursue and which to drop. They probably weren’t enough to support suspending Warren, which DeSantis’ aides knew would have to withstand a legal challenge.

They also dug up another joint statement that Warren had signed a year earlier, along with more than 70 other prosecutors and law-enforcement officers from around the country. In that statement, Warren pledged not to support the criminalization of medical professionals who provide gender-affirming care to transgender kids.

But DeSantis’ staff couldn’t cite a specific state law that Warren might be ignoring, so it probably wasn’t enough to sustain a suspension, either.

Then, on June 24, 2022, the United States Supreme Court issued its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, ruling that American women no longer had a Constitutional right to an abortion — and freeing states to pass laws making the procedure illegal.

Within hours, a criminal-justice reform group called “Fair and Just Prosecution” published the joint statement signed by Warren and more than 90 other prosecutors in which they vowed to “refrain from prosecuting those who seek, provide or support abortions.”

Florida already had a series of laws on the books limiting access to abortion. And DeSantis had just recently signed the state’s most far-reaching restriction yet: A ban on abortions after the 15th week of pregnancy, even for victims of rape, incest or human trafficking.

And here was Warren seeming to say that he would not criminally prosecute a doctor who performed an abortion on a woman who was 16 weeks pregnant.

A few weeks later, on Monday, July 18th, DeSantis general counsel Ryan Newman called an all-staff legal meeting in which Newman revealed that Larry Keefe had proposed suspending Warren based on his abortion statement, according to the deposition of Ray Treadwell, the chief deputy general counsel.

They began to work on a proposed executive order for DeSantis to sign.

The governor gets on board

The depositions suggest that DeSantis’ staff had, until that point, been keeping the governor out of the loop as they dug into Warren.

For instance, over the Fourth of July holiday, DeSantis and his family vacationed at a Montana ranch owned by Eddie DeBartolo Jr., a billionaire real-estate developer in Tampa and big DeSantis campaign donor, according to the deposition of Chronister, the Hillsborough County sheriff who also happens to be DeBartolo’s son-in-law. Chronister traveled to Montana for the holiday, too.

Chronister had been continuing to help DeSantis’ team gather information on Warren. He obtained case records from the Tampa Police Department on behalf of the governor’s office and arranged a phone call between DeSantis’ staff and a former city police chief, according to his deposition.

But Chronister said he didn’t mention any of that to DeSantis when he met him in Montana. “He was there with his family,” Chronister said. “I didn’t want to bug him and his family.”

By July 26th, though, it was finally time to go to the governor.

That day, three of DeSantis’ senior aides — Chief of Staff James Uthmeier, General Counsel Ryan Newman and Larry Keefe, the public-safety czar — met with the governor to ask DeSantis if he would be willing to suspend Andrew Warren over his pledge not to prosecute people seeking, providing or supporting abortions.

DeSantis was initially skeptical, according to an excerpt from a deposition of Newman.

After all, Warren had said he would not criminally prosecute people seeking or providing abortions — but he hadn’t yet declined to press charges in an actual case. In fact, in a court filing, Warren said his office has never been referred a single case involving a request to prosecute an abortion-related crime.

“His response was not particularly enthusiastic,” Newman said of DeSantis. “He expressed concern that suspension based on a pledge perhaps could be viewed as not a neglect of duty under the law.”

But Newman pushed back. Newman said he argued that a public pledge to not prosecute a certain type of crime was “even worse” than quietly dropping cases because it could encourage people to break the law.

That persuaded DeSantis, Newman said in his deposition.

“My impression is that that convinced the Governor, because his response back to me was, ‘Oh, yeah, well, I guess that’s right. What if somebody just declared that they’re not going to prosecute murder cases for certain classes of victim? Would the government just have to stand by and wait for the crimes to be committed?’” Newman recalled. “And I think we both agreed that, no, that can’t possibly be right.”

Once the governor and his aides agreed that they could suspend Warren on the basis of his abortion pledge, they quickly moved through some of the other information they’d gathered on Warren that could be used to buttress the decision.

The entire meeting, Newman estimated, took less than 30 minutes.

‘Non-abortion infractions first’

With DeSantis on board, the governor’s office began to move much more quickly on Andrew Warren. Records show they were motivated by politics as much as policy.

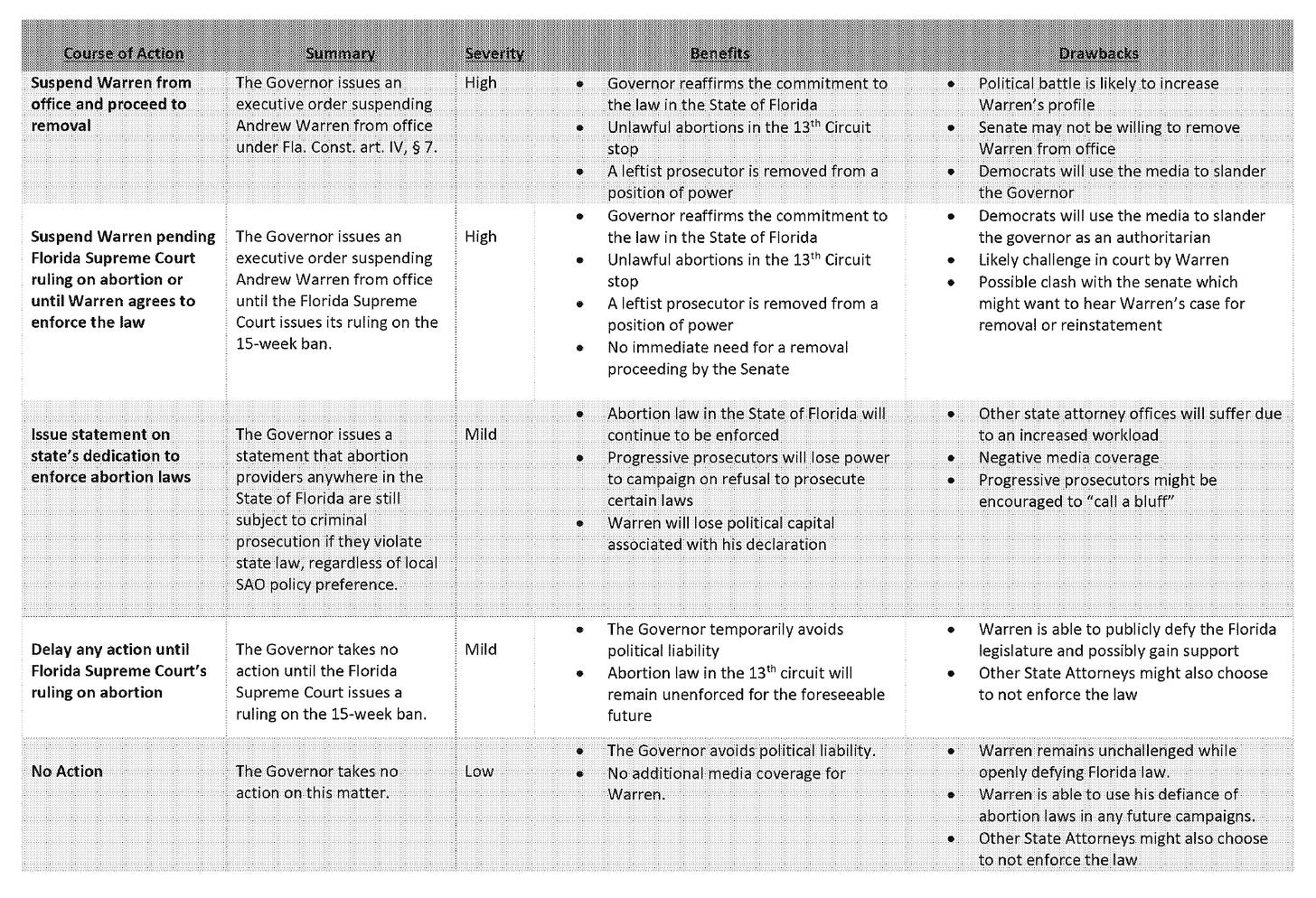

At one point, a staffer in the general counsel’s office prepared a memo examining the range of potential actions DeSantis could take against Warren — from suspension to warning to nothing at all. The document explained “benefits” and “drawbacks” of each option.

One of the benefits to suspending Warren? “A leftist prosecutor is removed from a position of power.”

One of the drawbacks? “Political battle is likely to increase Warren’s profile.”

Court records show the governor’s office also discussed the plan to suspend Warren with Anthony Pedicini, a prominent Republican political consultant and campaign strategist in Tampa.

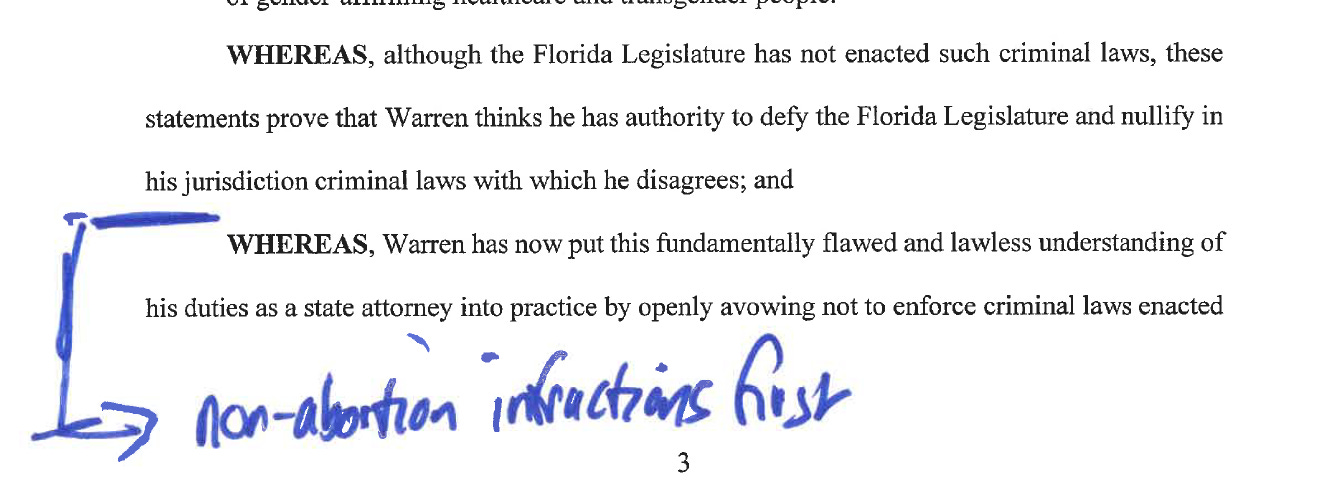

On Aug. 3 — one day before he announced the suspension — DeSantis met again with Uthmeier, his chief of staff, and Newman, his general counsel, to provide his personal edits to the proposed executive order.

DeSantis handed Newman a hard copy of the document onto which he’d handwritten notes in blue ink. The governor instructed his staff to add sensational language describing abortions as “dismemberment” of an “unborn child.”

But at the same time, DeSantis also ordered them to downplay the role abortion played in his decision. Near the beginning of the proposed order, DeSantis scrawled an instruction to list “non-abortion infractions first.” Lower down in the document, he drew a line to another paragraph and wrote, “put before abortion.”

It really was all about abortion

In fact, a number of DeSantis staffers seemed determined to spin the Warren suspension as about more than just taking out a pro-abortion prosecutor.

“This isn’t about abortion or any one thing, it’s about having accountability to our system of law and order to prosecute crime,” Kyle Lamb, an “Uber-driving conspiracy theorist blogger” who DeSantis hired as an analyst and researcher, Tweeted during a press conference in Tampa to announce the suspension. “There has been a pattern developing in Hillsborough County where one person picks and chooses which laws he wishes to enforce.”

That same morning, Christina Pushaw, DeSantis’ then-press secretary, texted other members of the governor’s communications staff to tell them that a producer for Fox News host Tucker Carlson had reached out. Pushaw assured the others that she would make sure “it’s framed the right way.”

Carlson ended up leading his show that night with a 12-minute monologue warning viewers of the danger posed by progressive prosecutors like Warren and praising DeSantis for suspending him. “Finally, someone is doing something about it,” Carlson said. Carlson didn’t mention abortion until the 10th minute.

And two days later, another DeSantis press aide — the records suggest it was Bryan Griffin, who was DeSantis’ deputy press secretary at the time — messaged other communications staffers to alert them to a new story published by the Epoch Times, a conservative publication. The aide told the others that the Epoch Times writer had “worked with me on edits” on the story, which published under the headline, “Removal of Florida State Attorney About Neglect of Duty and Is Not Political, DeSantis Says.”

“I think it does us a unique service of making the point that the suspension was about a BUNCH of factors, not just the abortion thing,” the aide wrote.

But one of DeSantis’ own attorneys later acknowledged, under oath, that the Andrew Warren suspension was driven entirely by “the abortion thing.”

In a deposition taken Oct. 31, Ray Treadwell, the governor’s chief deputy general counsel, said the general counsel’s office only recommended suspending Warren because of his pledge not to prosecute people seeking or providing abortions.

“It really was the abortion statement that drove Mr. Newman and I to the point of wholly recommending Mr. Warren’s suspension,” Treadwell said. “I don’t think those extra documents would have been presented to the governor without the abortion statement being with them.

“I will say emphatically that it was the abortion statement that drove our recommendation across the goal line,” Treadwell added.

More than $2 million in ‘free media’

DeSantis and his staff always knew Warren would challenge the governor’s decision to suspend him.

In fact, there’s some evidence that DeSantis himself grew concerned that all the triumphant Tweeting by his staff might accidentally strengthen Warren’s hand.

“Kyle, please immediately cease all tweets until we have a chance to meet 1-on-1,” Chief of Staff James Uthmeier texted to Kyle Lamb, the governor’s office researcher who was Tweeting during DeSantis’ press conference. “I know you’re just trying to help, but the boss is not pleased with the sensationalism of this overly legal proceeding. Every comment impacts what will be contentious litigation. No tweets at all unless directed by Taryn, I mean it.”

Taryn Fenske, DeSantis’ communications director, then sent a screenshot of Uthmeier’s text to others on DeSantis’ press team.

“Just between us,” Fenske wrote, “so let’s tread lightly and let the press sensationalize it through our facts and us walking the line.”

But they weren’t prepared for how Warren decided to challenge DeSantis’ action.

The records and depositions show that DeSantis’ office figured Warren might file a lawsuit in state court questioning the governor’s authority to suspend him. Or he might appeal to the Florida Senate, which, under the state Constitution, has the power to reinstate (or permanently remove) a local official suspended by the governor.

DeSantis had plenty of reason to be confident on both fronts. He has personally appointed a majority of the justices on the Florida Supreme Court, which has already ruled that DeSantis has wide latitude to suspend local officials.

And DeSantis wields enormous influence in the Republican-controlled state Legislature. Just last year, he single-handedly forced lawmakers to redraw the boundaries of the state’s Congressional districts in order to eliminate districts that had previously been represented by Black members of Congress.

But Warren instead decided to fight DeSantis in federal court by arguing that DeSantis’ suspension amounted to an unconstitutional infringement of Warren’s free speech.

“Neither of us at that time were thinking this was a First Amendment challenge,” Ray Treadwell, DeSantis’ chief deputy counsel, said in a deposition, referring to himself and DeSantis general counsel Ryan Newman.

And that makes the question of whether DeSantis only suspended Warren because of his abortion statement potentially critical to the case.

Of course, even if Andrew Warren wins, Ron DeSantis may have already gotten what he wanted out of this fight.

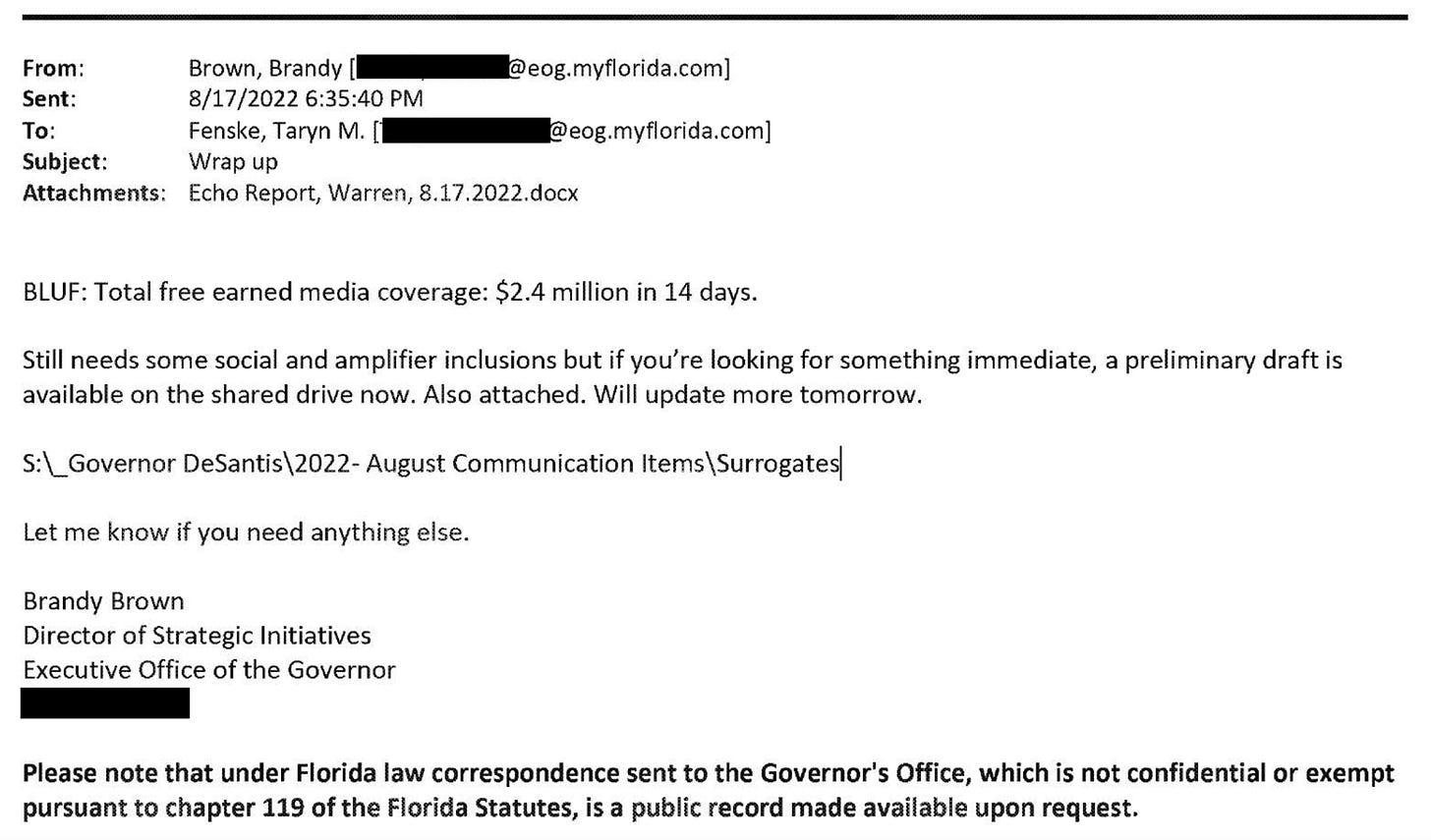

Two weeks after DeSantis suspended Warren — on the very same day Warren filed his federal lawsuit — a staffer in the governor’s office with the title of “director of strategic initiatives” emailed a report to Taryn Fenske, the governor’s communications director.

The report estimated that suspending Warren had earned DeSantis — who may launch a presidential campaign later this year — approximately $2.4 million in “free earned media coverage.”

The “free” publicity included nearly $1.3 million worth of coverage by national outlets like MSNBC, Fox News and CNN, plus another $140,000 of coverage in local media markets outside of Florida.

“Still needs some social and amplifier inclusions but if you’re looking for something immediate, a preliminary draft is available on the shared drive now,” the staffer wrote to Fenske. “Will update more tomorrow.”

What a detailed and superbly written column this is. Thanks to Seeking Rents for following this story.

He's despicable