The formulas home insurance companies use to set rates in Florida may become more secretive

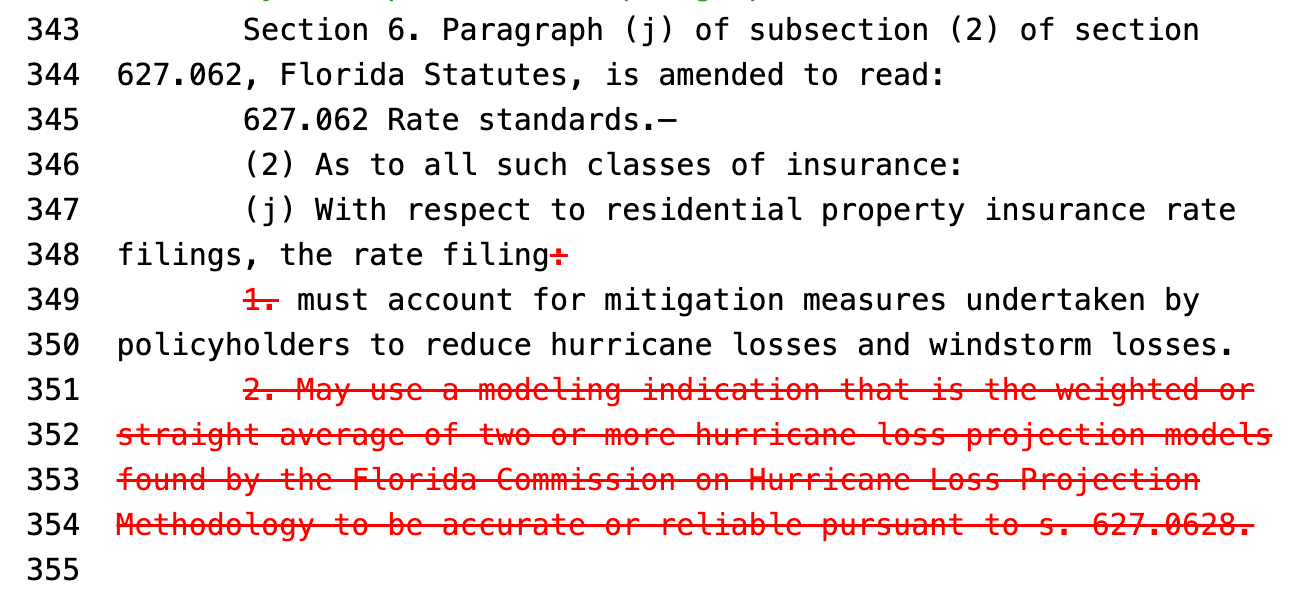

An industry-written law will allow insurance companies to "blend" proprietary computer models together when calculating the rates they charge Florida homeowners.

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter and podcast devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the journalism of others — that examines the many ways that businesses influence public policy across Florida, written by Jason Garcia. Seeking Rents is free to all. But please consider a voluntary paid subscription, if you can afford one, to help support our work.

The hidden algorithms that home insurance companies use to set rates in Florida may become even more of a black box.

It’s the result of an industry-written law that Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis and the GOP-controlled Florida Legislature passed last year, despite concerns raised by the state’s top insurance regulator.

The new law permits property insurers to combine multiple computer models when calculating the rates they want to charge Florida homeowners — a process known as “model blending.”

The use of computer models, which run simulations meant to estimate an insurance company’s potential exposure in the event of a hurricane or other catastrophe, has a fraught history in Florida.

The state has invested millions of dollars in taxpayer money over the years developing a public loss-forecasting model at Florida International University that insurance companies can use as part of their ratemaking process. But Florida also allows insurers to use proprietary models developed by private companies instead.

Private models must be reviewed and approved by a small state agency partly run by appointees of the governor and the chief financial officer. But most of the information that the modeling firms provide to the agency is kept secret from the wider public, which critics say makes the private models impossible to adequately evaluate. And insurance companies in Florida have a history of manipulating these opaque algorithms in order to justify demands for big rate hikes.

Altogether, Florida currently allows insurers to use models created and controlled by six private companies — as well as FIU’s public model — in their rate filings.

And now, under a new provision passed last year as part of Senate Bill 418, insurers can use as many of those models as they want in the same filing. Insurers can average models together or apply some kind of weighted formula.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with using more than one model. The Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund — the state-backed entity that sells publicly subsidized reinsurance to insurance companies — blends multiple models when setting its own rates.

Insurance companies, who have been lobbying to use model-blending themselves in Florida since at least 2020, say the goal is simply to produce more accurate rates. In talking points provided to legislators — which some lawmakers have at times read word-for-word in public hearings — the industry has said combining models can “promote the integrity of the ratemaking system, by leveraging available data.”

“The theory is that the more data and approved models that are used, the more reliable and accurate the rates will be,” reads one summary that was provided to lawmakers ahead of the Florida Legislature’s 2022 session and was obtained through a public-records request.

But allowing insurance companies that are already using non-transparent private models to combine them into even more secretive formulas also creates more opportunity for manipulation, particularly in large rate filings in which the state of Florida is subdivided into many smaller territories.

For instance, an insurer could potentially cherry pick projection results in order to generate higher-than-warranted rates — or to make the company appear financially stronger than it actually is.

Model blending also makes rate filings more challenging for regulators to effectively evaluate.

“We were concerned we wouldn’t be able to fully understand what it was the company was submitting,” said Florida Insurance Commissioner Mike Yaworsky. “It could be a filing that’s been effectively gamed for a purpose other than just determining what the actuarially sound rate is.”

Yaworsky was appointed to lead Florida’s Office of Insurance Regulation in March 2023 after the state’s previous insurance commissioner left to become a lobbyist. His office expressed concerns to Florida lawmakers last year about the model-blending legislation, but lawmakers passed it anyway.

But Yaworsky’s office successfully lobbied for further changes this session that he said add “guardrails” around the practice. Specifically, under provisions in House Bill 1611, an insurance company that averages models together when calculating its rates must apply the same average across the entire state.

“We wouldn’t want to see a different blended model used in different territories,” Yaworsky said.

And if an insurance company wants to use a weighted average, it must provide regulators with an “actuarial justification” that shows the combined model produces fair rates — although those explanations are likely to be kept hidden from any wider public oversight or evaluation. That’s because Florida lawmakers allow insurance companies to classify much of the information they submit to state regulators as “trade secrets,” which then exempts the materials from the state’s public-records laws.

Some people wanted to go even further.

Sen. Jay Trumbull, a Republican from Panama City, proposed repealing the model-blending law entirely at one point during this past session. Trumbull represents a part of the state that is still rebuilding more than five years after being struck by a Category 5 hurricane — and where many residents have experienced “insurance nightmares.”

“As we were going through the bill, my goal and intention was to make sure that we weren’t using two models that were the two more expensive models and that we were focusing on ones that were less experience,” Trumbull said during a January hearing in Tallahassee. “I really wanted to make sure that we were not allowing companies to take two of the higher weights, and really focus on trying to get the best premium at the least price for the consumer.”

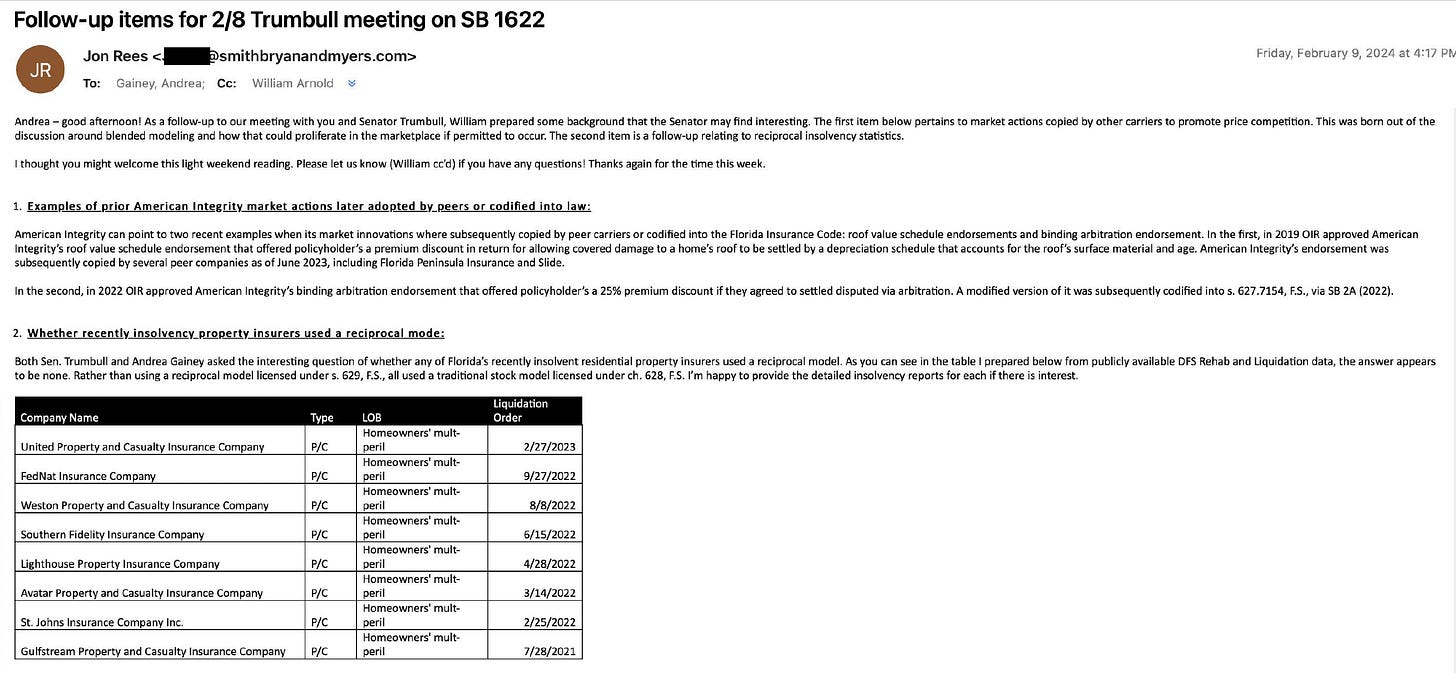

Trumbull, who did not respond to requests for comment, ultimately dropped his bid to undo the model-blending law. The decision came after at least one insurance company lobbied in favor of model blending.

Emails obtained in a public records request show that lobbyists for American Integrity Insurance, a Tampa-based insurer with nearly 300,000 residential policies in Florida, met with Trumbull to discuss “blended modeling and how that could proliferate in the marketplace if permitted to occur.”

American Integrity — which also lobbied for the initial 2023 legislation allowing insurance companies to combine multiple catastrophe models — suggested the practice could lead to more “price competition” among insurers.

It’s not clear how the company thinks model blending could lead to lower prices; executives at American Integrity did not respond to requests for comment. But there is reason to be skeptical the end result would be good for Florida homeowners.

As part of its pitch to Trumbull, the emails show that American Integrity cited two other “market innovations” that the company claimed it had developed and that were later copied by other insurance carriers in Florida. Both of those “innovations” essentially involved cutting prices by selling lower-quality insurance.

In one example, American Integrity began selling home insurance policies that were cheaper because they no longer covered the full cost of replacing a damaged roof. And in the other, American Integrity began offering discounts to homeowners who agreed to give up their rights to sue the company over unpaid claims and resolve disputes through industry-friendly arbitration instead.

It’s a testament to the persuasive power of property insurance companies in Tallahassee — particularly ones like American Integrity that also happen to be generous campaign contributors.

Campaign-finance records show that the company and its CEO have given more than $750,000 to Florida politicians over the past two years — including $195,000 to the Republican Party of Florida and related committees run by GOP leadership in the state House and Senate. Only a small handful of other property insurers have given more money.

American Integrity also woos key Florida lawmakers in other ways.

For example, separate emails show company executives scheduled a mid-session dinner this year with Rep. Bob Rommel, a Republican from Naples. Rommel chaired the House Commerce Committee, which oversees all insurance legislation.

The dinner was booked at The Huntsman, a high-end Tallahassee restaurant that sells $82 Wagyu strip streaks, $46 elk tenderloins, and $42 grilled Texas antelope. It was scheduled the evening before Rommel’s committee took up a pair of insurance bills that records show American Integrity was lobbying on.

Both bills passed. And Rommel, who has taken at least $40,000 from American Integrity over the years, is now running for election to the Florida Senate.

I’ll admit, something didn’t sound right— a company choosing the name — American Integrity. Not sure what using a backroom of spaghetti to choose premiums has to do with straight up comparisons of claims to premiums to denied claims. Reminds me of the Oracle of Delphi in Ancient Greece. Want the premium increase for next year? Go ask the Oracle.

It’s pay to play in Florida since Desantis has been in Tallahassee.