The mayor of Orange County plows ahead with a plan to pave a toll road through a forest

Orange County voters overwhelmingly opposed a plan to run a developer-backed toll road through a forest that was supposed to be saved forever. Mayor Jerry Demings doesn’t seem to care.

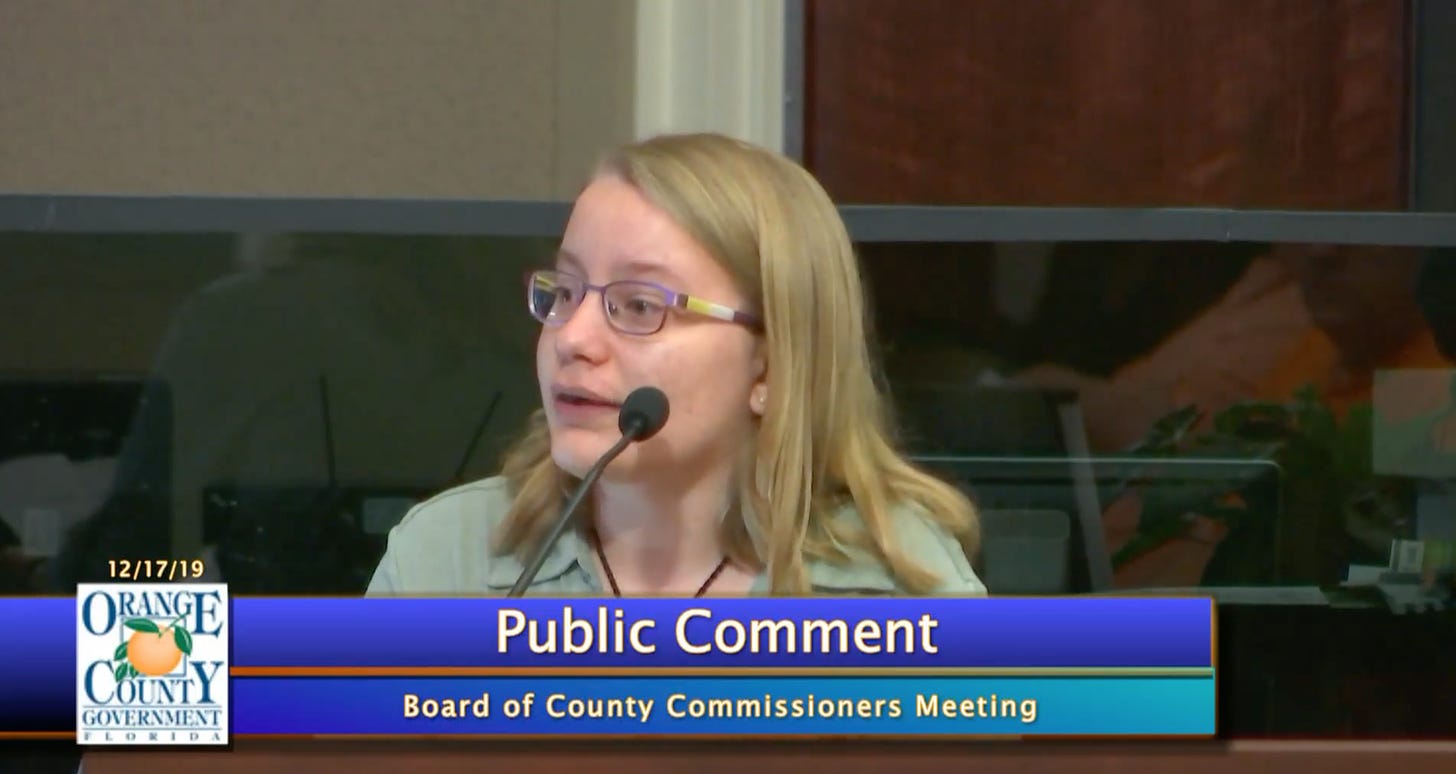

On a mid-December morning in 2019, shortly after Orange County Mayor Jerry Demings and county commissioners had opened up their final meeting of the year to public comment, a 13-year-old girl named Megan Sorbo marched up to the podium.

Demings and the rest of the county commission were about to vote on whether to build an $800 million toll road through a nearly 1,700-acre forest that had long ago been set aside for conservation. Megan wanted to stop them.

Megan had only a few moments to speak, and she nearly yelled into the microphone as she begged Orange County’s elected leaders to reject the developers lobbying for the new highway and to save the forest instead.

“This is something that me and my generation will have to live with for the rest of our lives,” Megan said. “Just because kids can’t vote doesn’t mean that we don’t care. Just because kids can’t decide who represents them doesn’t mean it’s okay to destroy the world that we’re all going to live in.”

Megan finished, drawing ragged breaths and fighting back tears of frustration. Demings paused for a moment to thank her for advocacy. “We admire your passion,” the mayor said.

Then he voted for the toll road.

It was, in hindsight, a sign of things to come.

That December 2019 vote — a 5-2 decision in which Demings and four other commissioners agreed to extend Osceola Parkway through the Split Oak Forest Wildlife and Environmental Area in order to support future development plans from The Tavistock Group — enraged Orange County voters.

A few months later, they threw one of the pro-toll road commissioners out of office, replacing her, in a landslide, with an environmental attorney who had supported the campaign to save Split Oak. And a few months after that, they passed a referendum meant to save the forest from the road, approving it with 86 percent of the vote — a level of support that most politicians can only dream of.

And yet, Demings — a Democrat whose wife, U.S. Rep. Val Demings, is running against Republican U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio — has continued to forge ahead with plans to run the road through the forest.

The history of Split Oak, which straddles the Orange-Osceola county line southeast of Orlando, is complicated and involves a number of different public agencies. (Florida’s legendary environmental journalist, Craig Pittman, has a great summary here.) But to get the road built, Orange and Osceola counties had to jointly apply for permission from a state agency called the Florida Communities Trust, which nearly 30 years ago provided money to help the counties buy Split Oak.

Two years later, the Trust’s governing board is scheduled to consider that application on Wednesday.

Orange County Commissioner Nicole Wilson, the Split Oak activist who was elected to the board in 2020, tried asking Demings to withdraw Orange County’s support for the application. He refused.

She also tried asking him to bring the Split Oak decision back to the county commission for another discussion — and potentially another vote. Demings refused again.

“Mayor Demings will not revisit the vote from December 2019,” a spokesperson for Demings said last week.

Why? Demings refused to answer that, too.

Well, here’s one potential reason: Tavistock — the most influential real-estate developer in central Florida, who needs this toll road to support a 24,000-acre housing project called “Sunbridge” — is one of Jerry Demings’ biggest campaign contributors.

Last month, records show that companies affiliated with Tavistock gave at least $14,000 to Demings, who is up for reelection this year. The donations included $6,000 in bundled contributions to the mayor’s campaign, plus another $8,000 donation to his political committee — which is named, ironically, “Orange County Citizens for Smart Growth.”

Of course, campaign contributions are just one avenue of influence. Tavistock has also hired the lobbying firm The Southern Group — where the Orlando office is run by the same lobbyist who led the political fundraising for Demings when he first ran for mayor in 2018.

(It’s hard to overstate how important it is to Tavistock that Sunbridge be a success. As big as that one community is — and early plans envisioned 37,000 homes — it’s also just the first step in a much longer-term vision to develop a far larger swath of ranchlands between Orlando and the Space Coast. All of it is owned by the Mormon Church’s Deseret Ranches, and Tavistock has spent more than 15 years cultivating a relationship with ranch leaders.)

This isn’t the first time Demings has rebuffed Split Oak supporters, either.

Following the 2020 elections, Demings had to appoint a county commissioner to the board of the Central Florida Expressway Authority, the agency that will build the Osceola Parkway extension. A coalition of environmentalists urged the mayor to pick a commissioner opposed to the new highway, citing the referendum that had just passed with overwhelming support.

Demings chose Commissioner Victoria Siplin — another toll-road backer.

With Orange County leaders refusing to reconsider, Split Oak activists are now turning to Tallahassee, in hopes of persuading the governing board of the Florida Communities Trust to reject the application submitted by Orange and Osceola counties.

Then again, that board is run by appointees of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis — who got $25,000 from one of Tavistock’s companies last fall. (Campaign-finance records suggest that donation came as part of a bigger fundraiser in which the Republican governor raised several hundred thousand dollars from Orlando-area developers, including Carson Good, one of the people DeSantis appointed to the agency that runs Orlando International Airport.)

Bipartisanship is alive and well in Florida…at least when it comes to campaign contributions and real-estate development.