The Ron DeSantis administration gave $16.5 million. The Ron DeSantis campaign got $200,000.

Florida’s governor and aspiring presidential candidate is raising enormous sums of money – much of it from people and businesses who want something from his administration.

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter and podcast devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the journalism of others — that examines the many ways that businesses influence public policy across Florida, written by Jason Garcia. Seeking Rents is free to all. But please consider a voluntary paid subscription, if you can afford it, to help support our work.

Earlier this year, the administration of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis did a big favor for one of Florida’s largest companies, when it awarded a $16.5 million grant to help pay for a new vehicle-processing facility for JM Family Enterprises at the port of Jacksonville.

A few weeks later, JM Family did a big favor for Ron DeSantis, when it donated $200,000 to the governor’s political fundraising committee.

Records show JM Family gave $100,000 to “Friends of Ron DeSantis” on Feb. 24. That was four weeks after the Florida Department of Transportation notified the Jacksonville Port Authority that it had approved the grant, which will cover half of the estimated $33 million construction cost of the custom-built vehicle-processing center for JM Family.

JM Family, which will pay for the other half itself, then gave DeSantis another $100,000 on April 13. That was two weeks before FDOT and JaxPort finalized the grant agreement.

A spokesperson for FDOT said the governor’s office did not play any role in the grant process (although the was ultimately approved by the agency’s secretary — a DeSantis appointee). A spokesperson for JM Family said the company never discussed the grant with the governor or his staff. And a spokesperson for JaxPort said the port authority would have covered the $16.5 million itself if the DeSantis administration hadn’t. (The port authority is run by a seven-member board, three of whom are appointed by the governor.)

The episode illustrates the extensive overlap between DeSantis’ political fundraising and the actions of his administration. The Republican governor, who is running for re-election this year and is widely expected to run for president in 2024, has raised more than $100 million since taking office in January 2019 — much of it in five- and six-figure installments from people and businesses who want something from him.

This wasn’t even the first example involving JM Family, a privately held company based in Deerfield Beach that does $18 billion a year in sales.

JM Family first donated to DeSantis’ political committee on March 10, 2021, giving the governor $100,000. That was nine days after DeSantis reappointed a JM Family lobbyist to the board of Enterprise Florida, the economic-development agency that helps private companies squeeze public incentive packages out of the state and local governments.

Drilling contractors become big donors

JM Family is hardly unique.

You probably recall the environmental disaster that struck in early 2021, when a containment stack holding wastewater from the former Piney Point phosphate plant in Manatee County sprung a leak. Worried that the structure might fail and inundate a nearby community of 300 homes with deadly flooding, officials dumped more than 200 million gallons of polluted water leftover from the phosphate-manufacturing process directly into Tampa Bay.

State leaders vowed to shut the troubled site down. To do so, the DeSantis administration helped craft a controversial plan to inject the remaining wastewater at Piney Point deep underground. It is the first time Florida has allowed phosphate process water to be pumped into the ground, which some critics have warned could contaminate drinking water.

DeSantis’ Department of Environmental Protection approved the permit for the injection well in December. One month later, the owners of the drilling company that got a $9.3 million contract to build that well became major DeSantis donors.

Records show that Timothy and Harvey Youngquist — the owners of Fort Myers-based Youngquist Brothers — gave $50,000 each in January to DeSantis’ political committee.

Timothy Youngquist gave DeSantis another $205,000 in March. His wife also donated nearly $17,000 worth of food and drinks to DeSantis’ political committee, suggesting the couple hosted a fundraiser for the governor.

The contract was awarded by Manatee County, and the consulting firm who recommended Youngquist Brothers for the job said the DeSantis administration wasn’t involved in that decision.

But Manatee County said the governor’s administration was involved in the initial decision to build an injection well. It also had to approve the drilling permit, which was issued after Youngquist had been hired.

‘There may be an ask’

In some cases, DeSantis donors need something from his appointees.

For instance, records maintained by Orlando International Airport show that representatives for a duty-free store contractor met in March with Carson Good, a Winter Park real-estate investor and DeSantis fundraiser whom DeSantis put on the board of the agency that runs OIA shortly after taking office.

Good said the company — Miami-based 3Sixty Duty Free, which operates two duty-free stores at OIA — wanted to give him an update on how its business is faring at the airport, where international traffic has yet to recover to pre-COVID levels.

During the worst of the pandemic travel slump, airport leaders waived or reduced fees several times for vendors, including 3Sixty Duty Free. But while domestic travel has since rebounded, international traffic continues to lag, which is prompting duty-free vendors like 3Sixty to seek more breaks.

“As I recall, there was no specific ‘ask,’ but they were saying their sales were still off,” Good said when asked about his March meeting with the company. “I suppose if sales stay slow, there may be an ask for relief in the future.”

Airport records show 3Sixty followed up its meeting with Good with additional meetings with three more of DeSantis’ appointees on the seven-member Orlando airport board.

In between those meetings, records show, the company wrote a $25,000 check to DeSantis’ political committee.

Veto insurance

Then there is the money DeSantis is raising from donors who want him to sign bills passed or earmarks stuffed into the state budget during the Florida Legislature’s 2022 session, which ended in mid-March.

For instance, the budget passed by the Legislature includes more than $700 million in spending to help a massive residential development in Senate President Wilton Simpson’s district. Called “Angeline,” the 10,000-home project in Pasco County is being jointly developed by Tampa-based Metro Development Group and Miami-based homebuilding giant Lennar Corp.

DeSantis is currently deciding which budget projects to allow and which to veto. While he does, Metro and an opaque entity with extensive links to Lennar are pumping money into his political committee — including $125,000 from Metro last week and $100,000 from the Lennar-linked entity (“Tread Standard LLC”) last month.

DeSantis also has yet to act on another priority of Simpson’s: SB 620, the so-called “Local Business Protection Act,” which aims to scare cities and counties out of regulating businesses by exposing them to the threat of expensive lawsuits.

One of the businesses that could most benefit from Simpson’s legislation is Petland, an Ohio-based pet-store chain that is the only national retailer that still sells puppies for profit.

A growing number of cities and counties have been passing local laws prohibiting stores from selling cats and dogs, as way to choke off demand for inhumane puppy mills around the county. Petland has been lobbying against these laws for years — and SB 620 could finally give the company the ability to stop them.

This isn’t a fringe activist concern: Records show DeSantis’ office itself fears that SB 620 would protect puppy mills.

But DeSantis has yet to say whether he’ll sign or veto the bill. And last week, Petland gave the governor $25,000.

Meanwhile, one of the most closely watched decisions facing DeSantis is what the governor will do about SB 2508 — yet another Wilton Simpson priority bill that is important to the state’s sugar industry. (The sugar industry is in turn funding Simpson’s campaign for Florida agriculture commissioner.)

Among other provisions, SB 2508 would make it harder for regional water management officials to change old rules that determine how water in Lake Okeechobee is used during water shortages.

Environmentalists, fishing guides, and others have been pushing to change those rules, which they say unfairly prioritize the irrigation needs of the sugar industry over the environmental needs of the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie Rivers and of the Everglades. But the sugar giants Florida Crystals Corp. and U.S. Sugar Corp. want to keep those rules in place.

DeSantis has famously warred with the sugar industry in the past and does not raise money from Florida Crystals or U.S. Sugar. But he raises lots of money — more than $2 million since he was elected governor — from Associated Industries of Florida... which is a notorious front group for Florida Crystals and U.S. Sugar.

AIF just gave another $100,000 to DeSantis earlier this month.

DeSantis also has yet to sign or veto a lower-profile bill that would strip cities and counties of the power to stop privately operated parking lots from issuing parking tickets.

The issue arose after a pair of local governments in South Florida — the city of Miami and Broward County — passed local ordinances in response to complaints that private parking lots were leaving misleading tickets on car windshields that suggested a failure to pay could lead to civil or criminal penalties.

So lobbyists for a pair of parking companies — City Parking Inc. and Professional Parking Management Inc. — turned to Tallahassee. They persuaded to pass SB 1380 this session.

Now, it’s up to DeSantis. The parking companies don’t appear to be leaving anything to chance: Records show City Parking and Professional Parking Management gave $25,000 each to DeSantis political committee last week.

A lucky billionaire

Some lucky donors have already had DeSantis sign their bills.

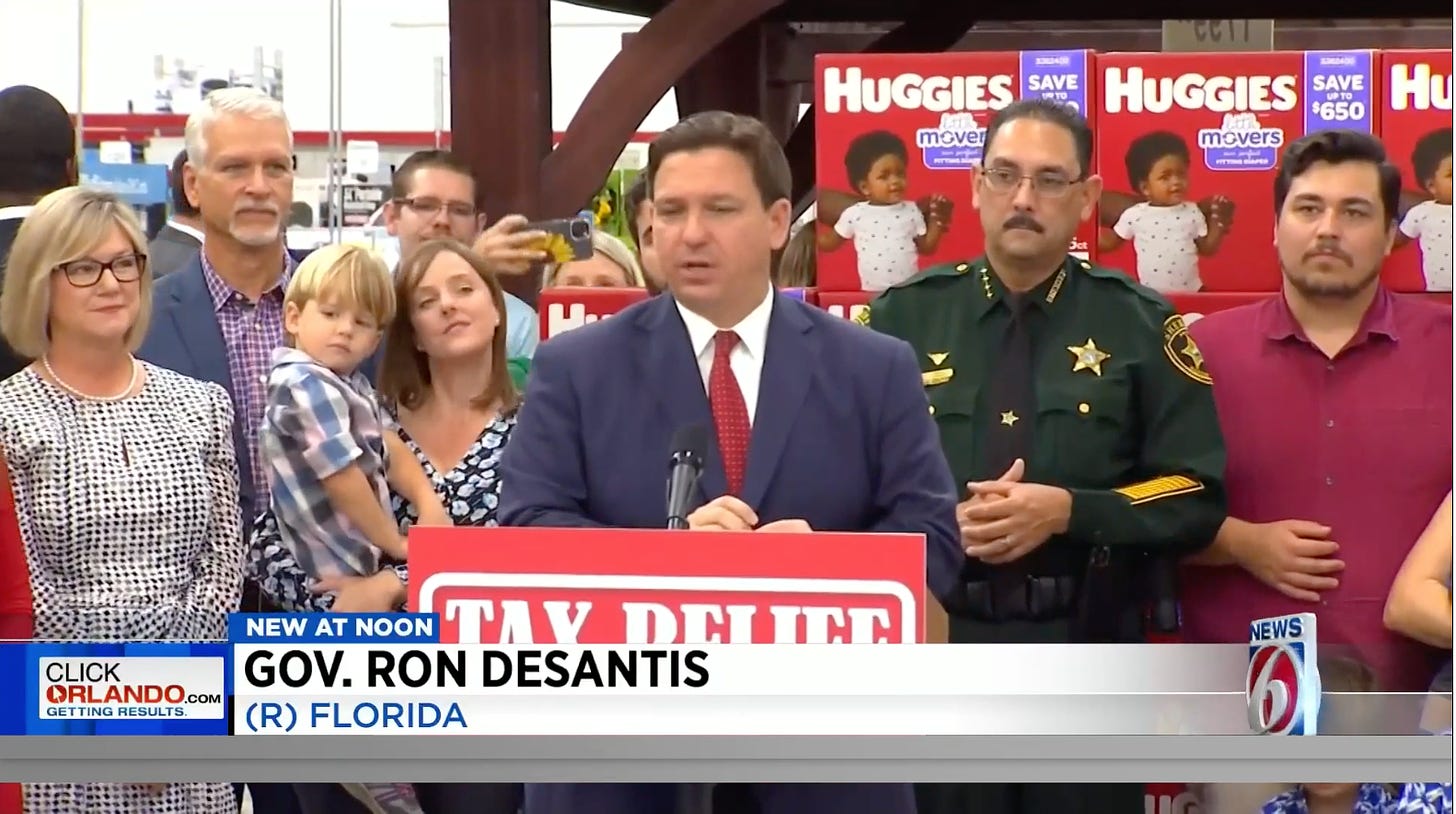

Earlier this month, DeSantis staged a signing ceremony at a Walmart in Ocala for HB 7071, $1.2 billion package of various tax breaks.

Standing in front of television cameras with boxes of Huggies piled high behind him, DeSantis told the crowd about some of the tax breaks he was about to sign into law — like a temporary tax break on baby diapers.

But the governor didn’t say a word about some of the other tax breaks he was approving at the same time — like a permanent tax break on tickets to Formula One Grand Prix races, which will cost the state $6 million a year in lost revenue in order to subsidize an annual Formula One race at Hard Rock Stadium in Miami.

Lawmakers stuffed that tax break into their tax package as a favor for Steve Ross, the billionaire real-estate developer who owns the Miami Dolphins — and Hard Rock Stadium.

Ross, who has been a generous donor to legislators in Tallahassee, made sure to show DeSantis some love, too. Shortly after the session ended, and before the governor acted on Ross’ tax break, records show Ross gave DeSantis $100,000.

Headline: "... businesses who something..."

DeSantis buys his way in office