A giant homebuilder wrote a Florida law to build housing subdivisions faster and cheaper

Records show a new state law meant to speed up construction of housing subdivisions was largely written by lobbyists for Lennar Corp., one of the nation's largest homebuilders.

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter and podcast devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the journalism of others — that examines the many ways that businesses influence public policy across Florida, written by Jason Garcia. Seeking Rents is free to all. But please consider a voluntary paid subscription, if you can afford one, to help support our work.

Gov. Ron DeSantis recently signed a bill that will let homebuilders across Florida throw up new housing subdivisions faster and cheaper.

The new law, records show, was largely written by Lennar Corp., one of the nation’s largest residential developers.

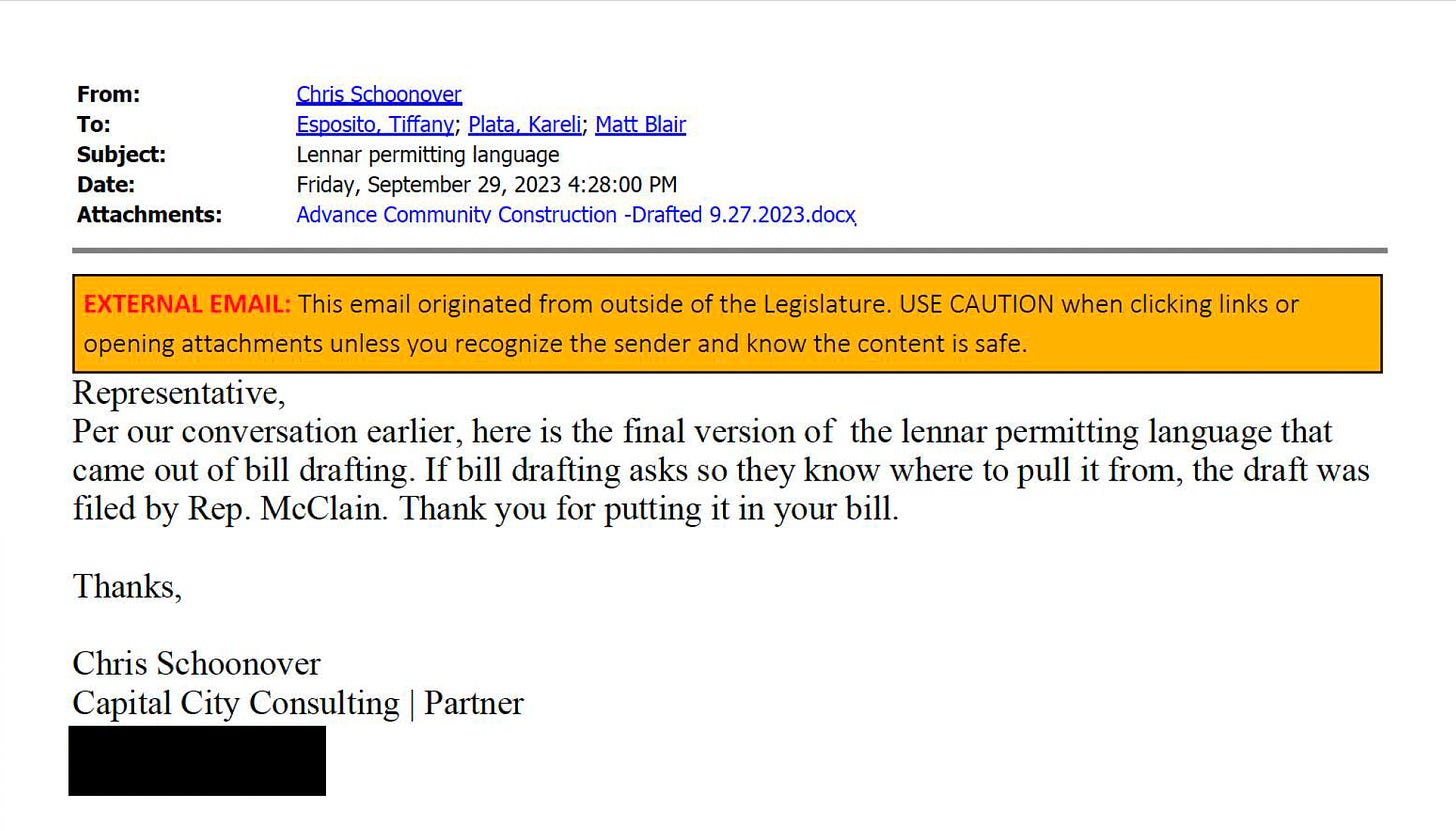

Dubbed by lobbyists as the “Lennar permitting language,” the legislation (Senate Bill 812) will compel cities and counties across Florida to issue building permits for most of the homes in a proposed subdivision before the development plans are finalized.

That’s not all. The bill allows homebuilders to hire private contractors in order to perform faster reviews of development applications. It enables them to more quickly lock in “vested rights” that shield them from any stricter development rules or environmental regulations that a community might adopt in the future. And it permits builders to begin selling future homes sooner.

Based in Miami, Lennar sold more than 73,000 homes last year at an average price of $446,000. The company framed its “advance community construction” plan as a way to help fill Florida’s shortage of affordably priced homes.

“This bill, if implemented properly, will accelerate the increased supply of much-needed housing for first-time homebuyers,” a lobbyist for Lennar wrote in talking points sent to several lawmakers that were obtained in public-records requests.

Campaign finance records show Lennar also gave its lobbyists $170,000 to spend last fall on campaign contributions for Florida politicians, right around the same time they were pitching the permitting bill to lawmakers.

Boosters estimated that the changes could shave as many as nine months off the time it typically takes to build a large housing subdivision.

“Time is money,” Rep. Tiffany Esposito, a Republican from Fort Myers who sponsored an early version of the bill, told the House Regulatory Reform & Economic Development Subcommittee during a December hearing. “So the longer that our developers and builders have to wait for permits to come in, the more expensive the end product is for consumers.”

Esposito tried to mask Lennar’s role in the legislation.

Emails show Lennar lobbyists sent their permitting proposal directly to Esposito, who then filed it within a larger piece of legislation dealing with building permits (House Bill 267). But during that December committee hearing, she denied that anyone had asked her to file the bill.

“This is my bill,” Esposito said, in response to a question from another legislator. “No one asked me to file it.”

Lennar’s legislation ultimately flew through Tallahassee this past session, clearing the House of Representatives on an 89-25 vote and passing the Florida Senate unanimously, despite opposition from environmental groups like 1000 Friends of Florida and Friends of the Everglades, which called it a “pro-sprawl” bill.

It’s pretty much inarguable that the law will lead to more suburban sprawl across Florida. For instance, the legislation says that any city that has at least 10,000 residents — and at least 25 acres of contiguous agricultural land — must allow homebuilders to use the accelerated approval process for subdivisions.

But then again, Florida really does need more housing. Housing supply is the main factor in housing affordability.

In that respect, the Lennar permitting law resembles the debate around another controversial gift that homebuilding lobbyists got from the Florida Legislature this session — a measure attempting to block a local ballot referendum in Orlando that would impose new development limits in rural areas.

That legislation was pushed through Tallahassee by a lobbying group whose members include Lennar and a pair of politically influential central Florida developers who are planning to develop a vast swath of cattle ranchlands between Orlando and the Space Coast.

Of course, allowing developers like Lennar to chew up more rural land for subdivisions full of detached single-family homes is not, by itself, a solution to Florida’s affordable housing crisis. State leaders must also do far more to promote higher-density development and support renters at risk of being priced out of their communities by gentrification.

(It would also be swell if DeSantis and Republican leaders in the Florida Legislature spared a moment to think about the workers who build these homes — instead of conspiring with industry lobbyists to protect homebuilders, farming companies and other businesses that deny water and shade to employees working outside in 100-degree heat.

Or if they actually strengthened protections for tenants in Florida — instead of working with the landlord lobby to take rights away from more than 1.5 million renters across the state.

But I digress.)

Florida did take an important step on affordable housing last year with the “Live Local Act,” a bulging package of grants, tax breaks and other changes championed by outgoing Senate President Kathleen Passidomo (R-Naples). But the early returns have been mixed.

For instance, a key provision in the Live Local Act is designed to spur construction of moderately priced apartments that are affordable to people who make too much money to qualify for traditional affordable housing. Supporters call it the “missing middle.”

But these tax breaks are so far mostly subsidizing housing at the very top end of the allowable price range — and even handing unintended subsidies to developers of student housing and luxury apartment complexes. The backlash has been so strong in some communities that legislators just passed a follow-up law allowing counties to opt out of some “missing middle” tax breaks altogether.

(This is, by the way, why tax incentives are often an inefficient way to achieve policy goals. Tax breaks are hard to truly target. And they too often turn into perpetual annual cash giveaways that pad the profits of companies doing exactly the same things they would do without the breaks. See, for example, here, here, here, and here.

Lennar itself last year helped push a tax break through the Florida Legislature for homebuilders that buy “graywater systems” — after Lennar invested in a company that makes graywater systems for homebuilders.

But I digress again.)

Perhaps the most radical changes in the Live Local Act are provisions that override local zoning controls and allow developers to build apartments with affordable units on any land designated for commercial or industrial uses. While that change has also sparked anger in some communities, overly restrictive zoning, which constrains housing supply, is a major driver of high housing prices and economic inequality.

But the Live Local Act stopped short of imposing zoning reform where it is really needed: Residential areas where development is restricted to single-family homes and where multifamily options like duplexes, triplexes, and quadriplexes are prohibited.

This is known as “exclusionary zoning” — and it seems to be a third rail of Florida politics. That’s probably because exclusionary zoning is fiercely protected by one of the most powerful rent-seeking lobbies of all: Existing homeowners, who financially benefit when a lack of housing supply makes their homes more valuable.

One community in Florida briefly attempted to do something about this.

In the fall of 2022, Gainesville became the first city in the state to eliminate exclusionary zoning, when city commissioners voted 4-3 to allow up to four units on all residential land.

But the decision sparked an uproar — one that Tallahassee politicians were eager to exploit. The DeSantis administration even tried to block the change. The decision baffled some of the supposedly free-market governor’s conservative supporters.

This might have become a bigger story, except Gainesville leaders quickly backed down themselves. In the spring of 2023, following a round of city elections, a new city commission voted 4-3 to restore single-family-only zoning.

DeSantis is destroying Florida. This fast track screams shoddy construction and cut corners. That should work well during hurricane season😕

It's remarkable how politicians can turn a naturally beautiful place like Florida into something so soulless and ugly with these Suburbistan developments. Paving over the last shreds of nature will really heat things up, more cars having to drive from these ugly boxes they call homes and neighborhoods just to be able to buy a loaf of bread will create worse gridlock and angry people at overcrowded beaches nobody can get to without a car they can't park. Nobody will be able to leave their homes or cars because it will be too hot and nature will be dead. I bet all the houses will be painted grey, too. Zombie zones made up of shelving units for grey robots, that's what these developments really are. I bet they will be built so fast and shoddy, the lawsuits will be flying. But I'm sure common prostitute DeSantis already took some money from his Company John to make it harder for home owners to sue.