Florida politicians may unleash the next generation of payday lenders

As the Florida Legislature convenes its 2024 legislative session, a battle looms over fintech payday loans that advocates say prey on low-income workers.

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter and podcast devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the journalism of others — that examines the many ways that businesses influence public policy across Florida, written by Jason Garcia. Seeking Rents is free to all. But please consider a voluntary paid subscription, if you can afford one, to help support our work.

Lawmakers in Florida may unleash a new generation of payday lenders on the state’s low-income workforce.

With the state Legislature about to open its annual lawmaking session, Republicans in Tallahassee have filed bills that would pave the way for a product peddled by few fast-growing tech companies — a product aimed primarily at workers at the very bottom of the wage scale who need money immediately but don’t qualify for traditional loans or credit cards.

The industry calls it “earned wage access,” or EWA for short. But it’s really just fintech’s take on payday loans: Short-term, small-dollar, and often-costly cash advances that consumers borrow through an app on their smart phone and then repay on payday.

The earned wage access industry is growing fast in a country where more than half of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck and two-thirds of employers only pay wages once every two weeks or less. One of the biggest players in the market — a tech “unicorn” called DailyPay — reportedly rejected a $2 billion acquisition offer last year. Walmart, one the largest low-wage employers on the planet, recently bought its own EWA company.

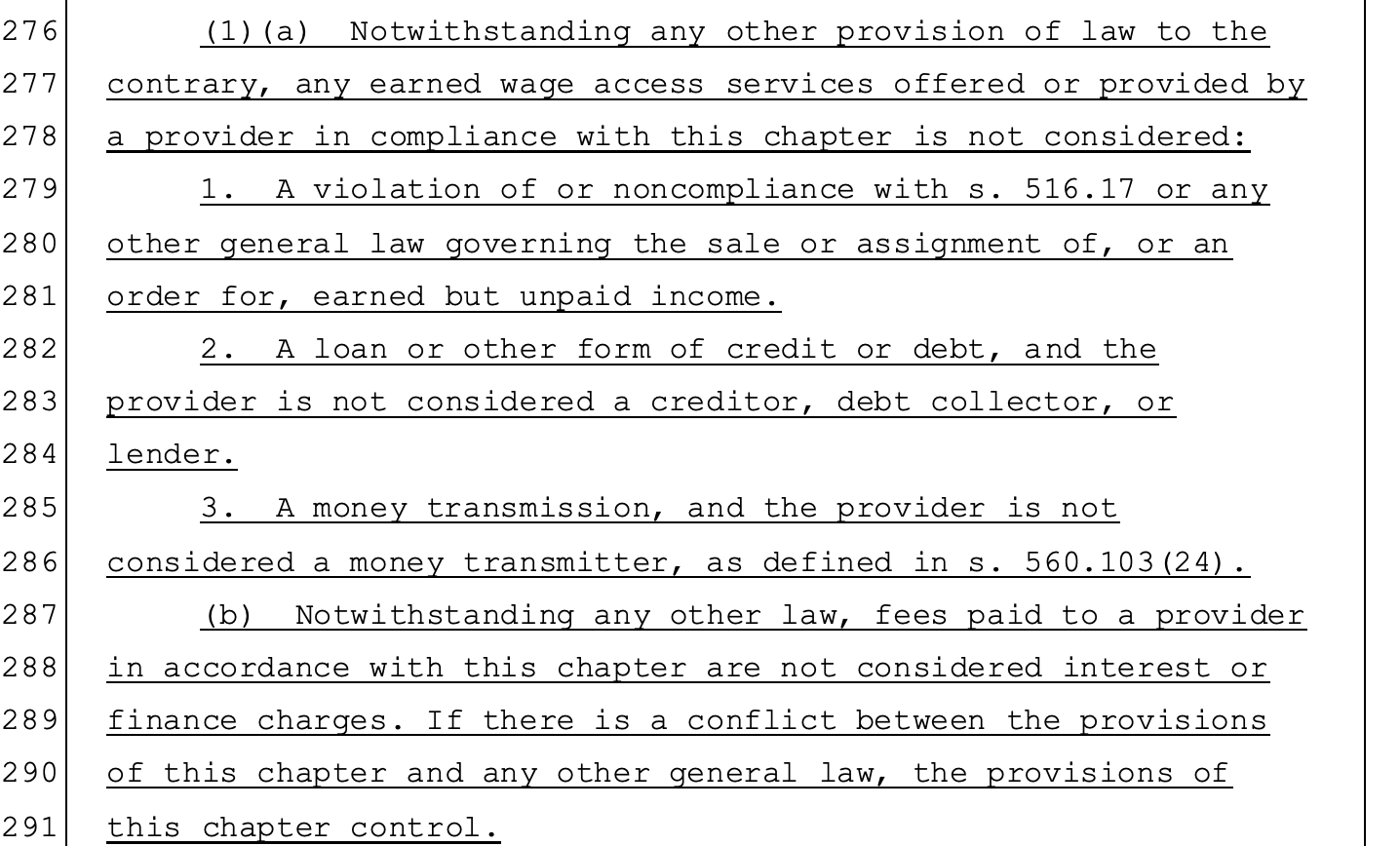

But as big as the EWA business has already become, it is operating in a legal gray area. That’s because earned wage access companies have been claiming they are not subject to the same laws that govern other consumer lenders.

And that has allowed these companies to sidestep important consumer protections — such as state usury laws, which limit the amount of interest a lender can charge, and the federal Truth in Lending Act, which forces lenders to disclose their costs in a clear and standardized way, so that consumers can accurately comparison shop.

Freed from such constraints, a growing body of research shows that the earned wage access companies have used complicated and non-transparent pricing to charge almost as much as traditional payday lenders — while potentially fueling cycles of overuse that leave workers paying to be paid.

Federal banking regulators have begun to more closely scrutinize earned wage access companies. But that has sent the industry and its allies scurrying to state Capitols around the country, lobbying legislatures to cement their current business models into state law.

The earned wage access industry appears to have three key goals: 1) To get EWA advances explicitly exempted from any existing lending laws and the consumer protections that come along with them; 2) To ensure EWA companies can charge unlimited fees on their loans; and 3) To allow them to charge those fees in opaque and often-misleading, ways — such as by soliciting “tips” that serve only to further pad a company’s profits.

The Florida legislation — House Bill 1009, sponsored by Rep. Toby Overdorf (R-Palm City), and Senate Bill 1146, sponsored by Sen. Jay Trumbull (R-Panama City) — accomplishes all three goals for the industry.

It is functionally the same as model legislation drafted by the American Legislative Exchange Council, the conservative, corporate-funded advocacy group that was chaired last year by one of the most powerful lawmakers in Florida: Rep. Danny Perez (R-Miami), who will become speaker of the state House following the 2024 elections. The Florida bills also largely match industry-backed laws passed last year through state legislatures in Nevada and Missouri.

But some consumer advocacy groups are pushing back. And several other states — including California, Connecticut and Maryland — are moving to regulate advances made through earned wage access apps just like other consumer loans.

This seems destined to become a big debate during the Florida Legislature’s 2024 session, which begins in less than a week. At least two large EWA providers — DailyPay and EarnIn — recently hired lobbyists in Florida. So has the American Fintech Council, which lobbies for the earned wage access industry and signed up Ballard Partners, the lobbying firm run by one of Florida’s biggest Republican fundraisers.

That’s not all. The big-business lobbying group Associated Industries of Florida — whose sponsors include low-wage employers like Amazon and the parent company of Universal Studios theme parks — has made passing an industry-friendly EWA law one of its top priories.

So, with Florida politicians about to decide whether to set all these fintech lenders loose, it’s probably important that we all understand what that would mean.

How does earned wage access work?

There’s quite a bit of variation across earned wage access companies. But the industry basically uses two main models.

The first is sometimes called “business-to-business” or “employer-integrated.”

Under this model, an employer will contract directly with an EWA company to offer early-wage access as a benefit for employees. The EWA company will integrate into the employer’s payroll systems, so it knows exactly how much money an employee has earned but not yet been paid. The employee can then install the EWA company’s app on their phone and use it to request cash advances, which are typically capped at something like 50 percent of wages owed.

The EWA company gets repaid on payday, through automatic paycheck deductions

DailyPay, which records show hired Florida lobbyists in August, offers employer-integrated earned wage access. The company’s clients include low-wage giants like Target, DollarTree, and Six Flags. It also works with HCA Healthcare, the hospital company that is one of Associated Industries of Florida’s largest funders.

The second EWA model is sometimes called business-to-consumer or direct-to-consumer.

Under this approach, there’s no employer involved. Instead, a consumer can download an EWA app directly from an app store and connect it to their personal bank account. They may have to provide some proof of employment or wage history, but there’s no continuing link to ongoing wages. Once set up, the user can request cash advances up to a dollar limit, like $500 per request.

A direct-to-consumer EWA company also gets repaid on payday. But it gets the money by pulling funds directly out of the consumer’s bank account.

One of the larger direct-to-consumer EWA providers is Silicon Valley-based EarnIn, which says it has made more than $15 billion in loans — and which also agreed to pay $12.5 million to settle a class-action lawsuit brought by customers who incurred bank overdraft fees as a result of EarnIn’s withdrawals.

Records show that EarnIn hired a pair of Florida lobbying firms in November.

How much does EWA cost?

While many earned wage access companies say that their service is available for free, the truth is that most borrowers usually end up paying fees — a lot of them.

In fact, a recent survey by researchers at Harvard University found that fewer than 40 percent of EWA borrowers were using their apps for free. (The results of that survey were incorporated into a larger working paper that those Harvard researchers wrote about earned wage access; I’m going to be referring to it a lot, and I cannot recommend it enough as a resource for understanding the industry.)

There are typically four types of fees tied to EWA apps:

Subscription fees: These are monthly fees paid to access services through an EWA app. The subscription usually includes access to several services — like budgeting software — rather than just cash advances

Transaction fees: Charged every time a user requests an advance

Expedited or express-delivery fees: When a user requests a cash advance, they will typically get the money in 1 or 2 business days. But they can pay an extra fee to get their money sooner — for example, $2 to get their money by the end of the day or $10 to get it instantly

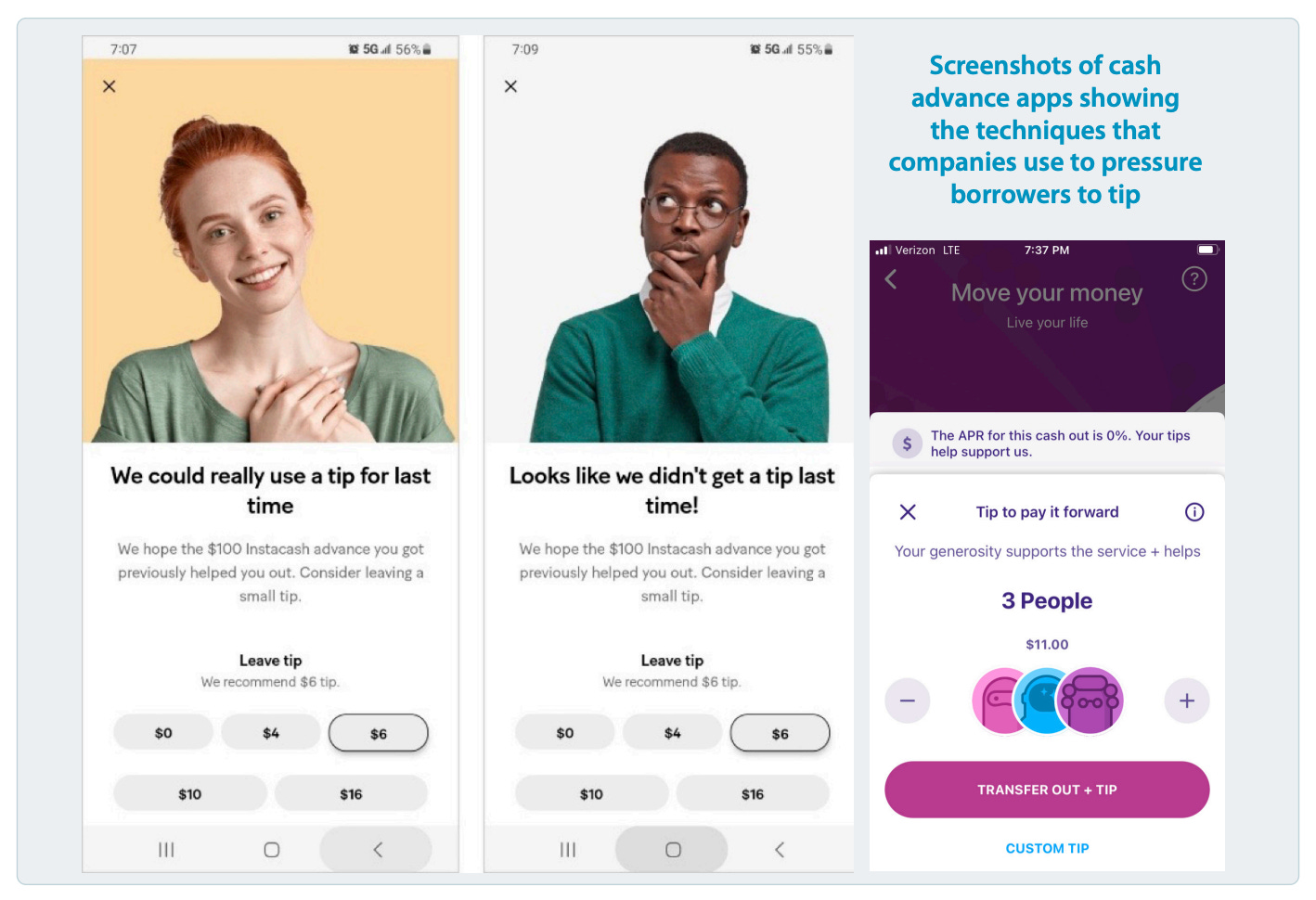

“Tips”: Voluntary payments that EWA apps press users to make whenever they request an advance, often using deceptive tactics. Despite the name, these aren’t “tips” in any normal sense of the word — all the money goes to the EWA company itself, rather than some individual person who has provided a service

Most earned wage access companies will charge some combination of fees, though only direct-to-consumer EWA providers will solicit “tips” from workers.

Good: Liquidity for the unbanked

To be very clear, earned wage access can be good for workers. It’s a way to provide liquidity to people who make very little money and who have poor credit histories (or no credit history at all).

EWA companies do not check credit, so there is no credit-score penalty for signing up. There are no rollovers, which happens when a borrower can’t afford to repay when their current loan comes due and refinances with a new loan instead. And EWA providers do not pursue borrowers who fail to repay their loan, such as by selling to debt collectors or suing in small-claims court. They simply won’t let the user request another advance.

Industry advocates often tout the fact that they do not chase after unpaid debts — making their loans “non-recourse” — when lobbying for exemptions from lending laws.

Of course, they can afford to forego debt collection because these loans are so safe from the lender’s perspective: They are for very short terms and small amounts, and — in the case of employer-integrated EWA advances — they are directly tied to verified wages. By one estimate, EWA advances are successfully repaid 97 percent of the time.

The employer-integrated advances can also be safe for borrowers, since the EWA company is not pulling directly from the borrower’s bank account and there is no risk of overdraft fees. And if an employer agrees to front all the fees themselves, then earned wage access really is a genuine benefit for its employees.

Finally, EWA advances are — potentially, at least — lower-cost options for people who lack access to bank accounts or credit cards, particularly compared to other alternative-finance products like standard payday and pawnshop loans.

This is one of the industry’s main talking points: One EWA company — Los Angeles-based Rain, which works with fast-food franchises like McDonald’s, Burger King and Taco Bell — claims that it empowers people “to kill predatory financial products like payday loans.”

Bad: costs comparable to payday loans

But the truth is that cash advances through earned wage access companies often turn out to cost borrowers almost as much as those other predatory financial products they claim to be killing.

For instance, in 2021, the state of California struck agreements with more than half a dozen EWA companies — including DailyPay and EarnIn — that required the companies to submit detailed reports on their cash advances every quarter.

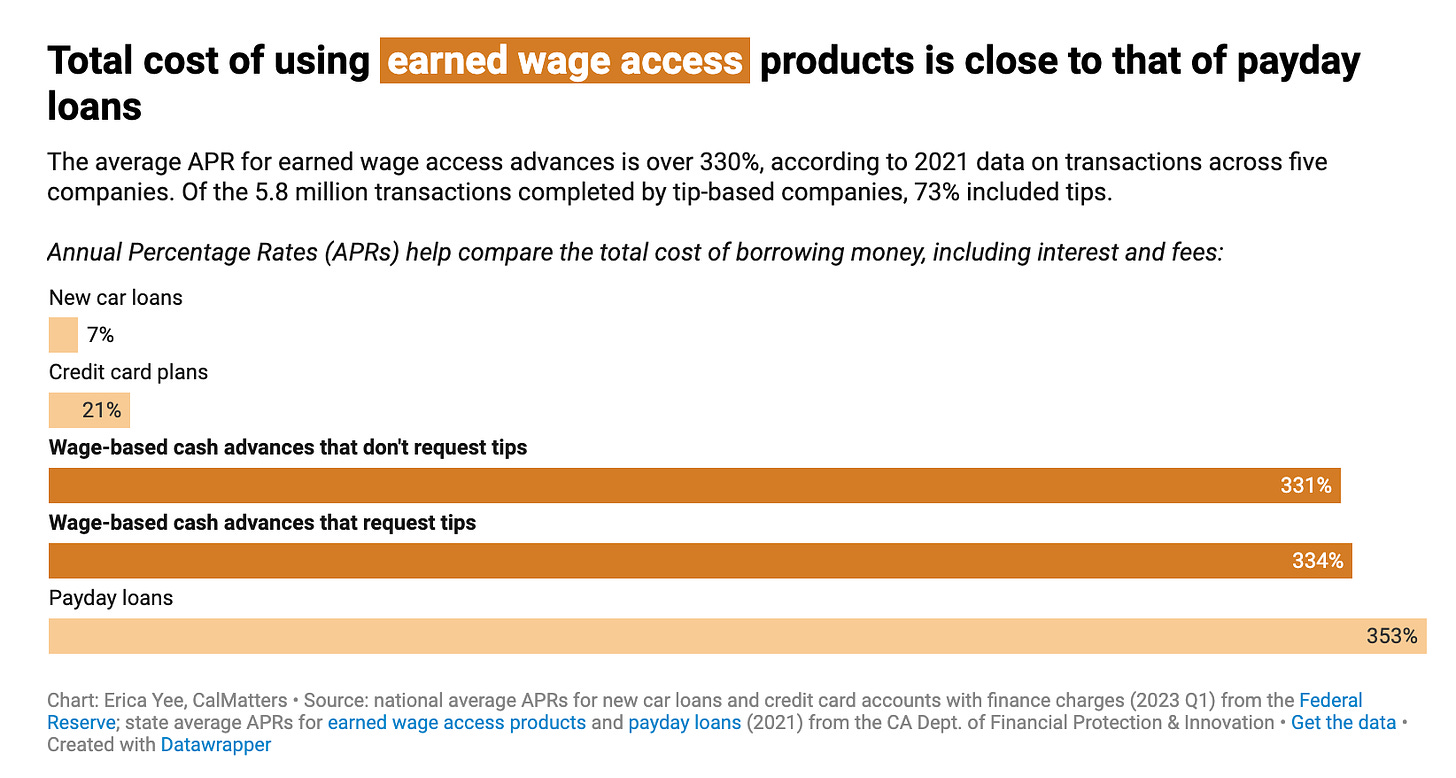

Those data showed that the EWA companies were, on average, charging borrowers the equivalent of a roughly 330 percent annual interest rate. That’s about the same as the interest rates charged by standard payday lenders in California.

There are a few reasons EWA advances can become so expensive. Since there is no cap on how much these companies can charge borrowers — and so little transparency about what is being charged and how the total compares to other types of loans — the fees can quickly stack up.

For instance, many workers taking out EWA advances need the money immediately; paying an expedited or express-delivery fee is, from a practical perspective, mandatory. “If you need the money now and you have to wait two days otherwise, that’s not free,” a 63-year-old home health aide and EarnIn user who regularly pays a $3.99-per-transaction “Lightning Speed” fee, told the Los Angeles Times earlier this year.

EWA companies that solicit “tips” can be particularly predatory. Consumers, regulators and advocacy groups have reported all manner of tactics companies use to either trick or pressure borrowers into tipping.

Tip-based companies will routinely set default tips amounts that are hard to change. Some will not obviously advertise that tipping is optional or make it very difficult to set the tip to zero. Some will disable certain features for borrowers who do not tip. And some will prey on people’s desire to help one another, by misleadingly implying that a tip will help some other vulnerable person.

What’s more, while the industry often claims that EWA advances help people confronted with an unexpected financial emergency, the data show that many users become regular borrowers.

The transaction data submitted by companies in California showed the average EWA user was taking out an advance three times a month — and some users were borrowing twice a week. And the survey conducted by the researchers at Harvard found that 41 percent of respondents who had access to an EWA app through their employer were borrowing once a week.

That same Harvard survey found that 75 percent of EWA borrowers were using their money to pay their regular bills — not just unexpected, emergency expenses. “It just turned into a cycle of always taking money out,” one respondent said.

The risk is that consumers will get caught in similar traps as they do with traditional payday loans — where borrowers are endlessly taking out new advances to cover the gap in their wages left by the repayment of the last advance, while incurring a new set of fees every time. The long-term result is that workers will have lower net earnings and reduced ability to build wealth for themselves and their families.

Cash advances through direct-to-consumer EWA apps are especially dangerous because of the risk of expensive overdraft fees that comes from allowing a lender to withdraw directly from a personal bank account.

The risk is magnified by the fact that many borrowers use more than one EWA app at a time; that survey by researchers at Harvard found that nearly 1 in 10 respondents using direct-to-consumer EWA apps had five or more apps on their phones.

What to do?

So, to channel John Oliver, what can we do?

Well, what we should do is pay people better than sub-poverty wages that force them to seek out exploitive loans just to make basic ends meet. But since Florida’s Republican-controlled Legislature is actively working on bills to help businesses reduce wages for workers, that’s probably not going to happen. At least not this session.

But Florida lawmakers could choose to regulate cash advances made through earned wage access apps just like other loans — since, you know, these are loans. That would subject them to the same interest rate limits and transparency rules, and give consumers the tools to make apples-to-apples comparisons between loan products.

As the authors of that Harvard paper concluded, “Especially when earned wages of workers are concerned, clarity is of the utmost importance and all transactions should have APR [annual percentage rate] equivalents posted and explained.”

And if Florida lawmakers aren’t willing to do that, then they should, at a minimum:

Set strict caps on the total fees that earned wage access companies can charge. One advocacy group — the National Consumer Law Center — has proposed a $5 per month limit on all charges, for instance.

Prohibit “tips.” We don’t let Bank of America, Visa or Amscot pressure their customers for tips. We shouldn’t let EarnIn do it, either. Short of that, EWA companies should be required to set default tip amounts to zero. And any “tips” should count toward the cap on fees.

Prevent EWA companies from pulling funds directly out of a borrower’s bank account — or make them responsible for any and all overdraft fees caused by failed withdrawals. Or limit EWA advances to employer-integrated models only.

Require employers offering earned wage access as an employment benefit to cover all fees associated with advances. Business have plenty of incentive to offer EWA already: Reducing financial stress for employees improves productivity, and an EWA option can help with recruiting. So employers don’t need to foist these extra fees onto their own workers to make it worthwhile.

Compel earned wage access companies to report detailed transaction data to the state. If Florida lawmakers really want to unchain a bunch of fintech payday lenders, the least they can do is be clear-eyed about it.

First, this is an amazing piece of investigative journalism. Thank you for digging deep and shedding light on this predatory product. What is scary is this bill will be so hard to not only defeat but to even amend with your excellent, common sense suggestions. The Florida legislature seems willing to let fintech make its investors happy on the back of the folks checking you out at Walmart or Target.

If you don't want to incur the costs associated with EWAs, why use them? There has to be some other form of payment low income workers can get. Possibly a high interest, as if they are not all high, credit card that is paid off each month. That may be better.

Limiting the fees and setting the "tipping amount", which I find ludicrous anyway, to zero without penalty, would be great, as long as they can still get interest on the loan. They may be forced to start to do more collections, but only time would really tell on that if the fees are capped.

I'm not sure if I like the fact that there are borrowers in a class action that sued because EWAs caused overdrafts. That same thing can happen if you are not using EWAs but have companies go directly to your checking account. I do like work-place based EWAs better. However, I don't believe it should be the companies that pay the fees. If I don't use the EWA, why should I "pay for" others to use it? That doesn't seem fair to the person that doesn't use it. Keep in mind, corporations will make how ever much money they want to make. If you charge them more, they will charge the consumers more which in turn will cause the people that require the EWAs to require them more and those that don't currently use EWAs to possibly need to use them. It's called inflation. Every time costs go up for a company, costs go up for consumers are well.