Records show DeSantis wanted to make university president searches a secret

DeSantis allies used the new law to install a politician as president of the University of Florida. And now lawmakers are advancing bills to hide even more of DeSantis' maneuverings from the public.

This is Seeking Rents, a newsletter and podcast devoted to producing original journalism — and lifting up the journalism of others — that examines the many ways that businesses influence public policy across Florida, written by Jason Garcia. Seeking Rents is free to all. But please consider a voluntary paid subscription, if you can afford it, to help support our work.

Last year, after blocking similar bills for years, the Florida Legislature passed a new law that conceals the identities of people applying to become president of a state university.

The sudden change of heart in the state Capitol came after the issue picked up an important behind-the-scenes supporter: Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis.

Newly released records show that senior staffers in the DeSantis administration wanted to let university boards — which are ultimately controlled by people appointed by the governor — conduct their presidential searches in secret. One of the governor’s top university appointees personally urged lawmakers to support the legislation. And DeSantis himself rushed to sign the bill into law as quickly as possible.

The controversial change had an immediate impact: Just a few months later, the board that runs the University of Florida used the new law to hand the school’s top job to a politician — former U.S. Sen. Ben Sasse (R-Nebraska) — without publicly considering any other candidates.

Details of DeSantis’ role in the secret-search law come as Florida lawmakers are considering even more anti-transparency bills this year — bills that would further shield DeSantis and other state politicians from public scrutiny.

One new proposal — which the Florida Senate could vote on this week — would allow DeSantis to hide details about where he travels and with whom he meets. The sweeping legislation would conceal records related to all of DeSantis’ past and future travel. It has surfaced in Tallahassee just weeks before DeSantis is expected to launch a campaign for president.

Another measure would let the governor and other politicians mask their campaign contributors for longer periods. It would be the first time that Florida has weakened its campaign-finance reporting rules in at least 25 years.

A spokesperson for the governor declined to say whether he is working with lawmakers on either idea. But open-government advocates suspect DeSantis is driving them through the Legislature.

“It’s coming from the Governor’s Office,” said Barbara Petersen, the executive director of the Florida Center for Government Accountability, which helps news organizations obtain public records.

Petersen, who has been working with and watchdogging Florida governors and Legislatures since the 1990s, said last year’s law and this year’s bills are part of a deliberate effort by DeSantis to weaken Florida’s famously strong transparency laws.

Plenty of previous governors — Republicans and Democrats alike — have chafed under the state’s “Government in the Sunshine” rules for public records and open meetings, Petersen said. But none have tried to “eviscerate” those laws like DeSantis.

“He’s the guy who turns out the lights,” Petersen said.

An administration that tries to hide its tracks

Since taking office in January 2019, DeSantis has gone to unprecedented lengths to hide the inner workings of his administration from the public.

The governor argues that he is entitled to “executive privilege” — as if he were a United States president — that allows him to keep some state records confidential. Senior staffers communicate with private email addresses and encrypted messaging apps, sometimes using pseudonym accounts. The governor himself avoids electronic communications entirely and delivers instructions to staff via unlabeled, handwritten notes.

DeSantis has also signed a battery of bills that that cut off public access to government records and meetings.

One of those bills hides the drugs that are used in death-penalty executions — and the drug companies that make them. Another bill closes off court proceedings involving a type of trust company used by billionaire families like the Walmart heirs to shield their wealth from taxes. And a third allows the political appointees who regulate Florida’s big private power companies to hold some of their hearings in secret.

But none has proven more controversial than the legislation DeSantis signed last year (Senate Bill 520) that conceals the names of people trying to get themselves hired as president of a state university or community college.

Under the new law, the identity of anyone who applies for a presidential job opening is kept confidential and exempt from the Florida’s public-records laws. Only the names of those chosen as finalists are revealed — and only shortly before the school’s board of trustees votes on who to hire.

It’s an idea that had been been floating around the Florida Legislature for a long time. Similar bills had passed the state House of Representatives four times in the past eight years.

But they had always failed in the Florida Senate — until last year, when the legislation squeaked through the Senate by two votes. (The bill, it’s worth noting, only passed because four Democrats voted for it: Janet Cruz of Tampa; Shevrin Jones of Miami Gardens; Darryl Rouson of St. Petersburg; and Linda Stewart of Orlando.)

Emails obtained in a public-records request show that the DeSantis administration wanted to get this done.

As the legislation moved through the process last year, there was some tension between leaders in the House, who wanted to keep names secret until as late as two weeks before a final vote, and in the Senate, who wanted names revealed at least three weeks in advance. The House eventually relented and drew up an amendment to match the Senate’s position with about three weeks left in that year’s session.

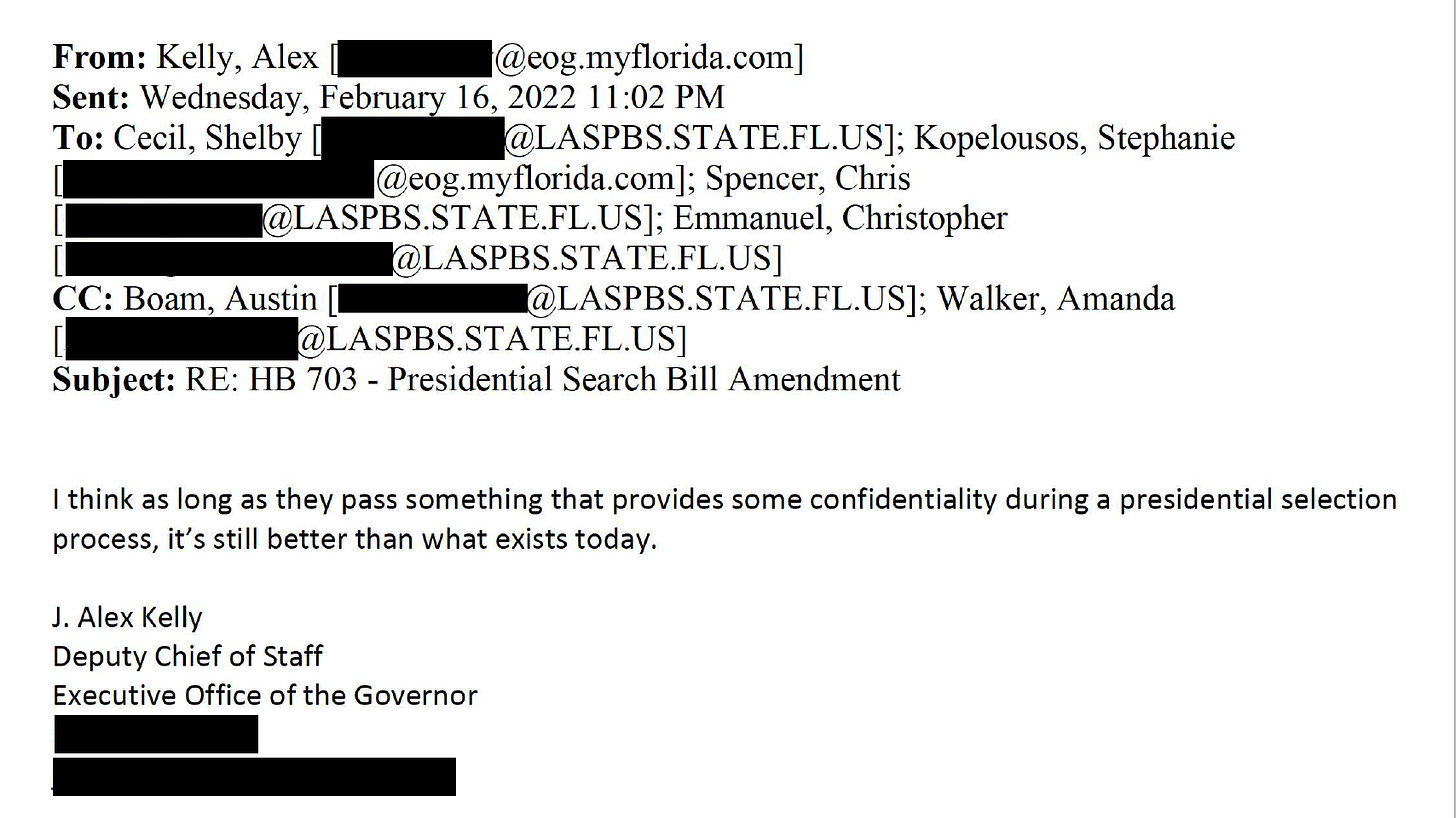

The Governor’s Office was closely tracking the legislation. A staffer immediately flagged the amendment for some of DeSantis’ senior-most aides — including his legislative affairs director, his budget director, and his deputy chief of staff in charge of education policy. The deputy chief of staff, Alex Kelly, advised the group they should accept the compromise.

“I think as long as they pass something that provides some confidentiality during a presidential selection process, it’s still better than what exists today,” he wrote in an email.

The records don’t show whether DeSantis or his office helped write the legislation, although the Governor’s Office has yet to produce all the emails from this public-records request. Kelly did not respond to a request for comment.

But the state senator who sponsored the bill — former Sen. Jeff Brandes (R-St. Petersburg) — said DeSantis was “supportive” as it moved through the process.

What’s more, Brandes said the effort was helped along by an important DeSantis ally: Mori Hosseini, a Daytona Beach-based real-estate developer and major DeSantis fundraiser whom the governor has appointed to the board of trustees for the University of Florida.

Brandes said Hosseini called some lawmakers to ask them to support the bill. “I know he engaged with certain members of the Legislature,” Brandes said.

Hosseini — who is the chairman of UF’s board — did not respond to a request for comment.

The records also show that DeSantis rushed to sign the secret-search bill into law as quickly as possible.

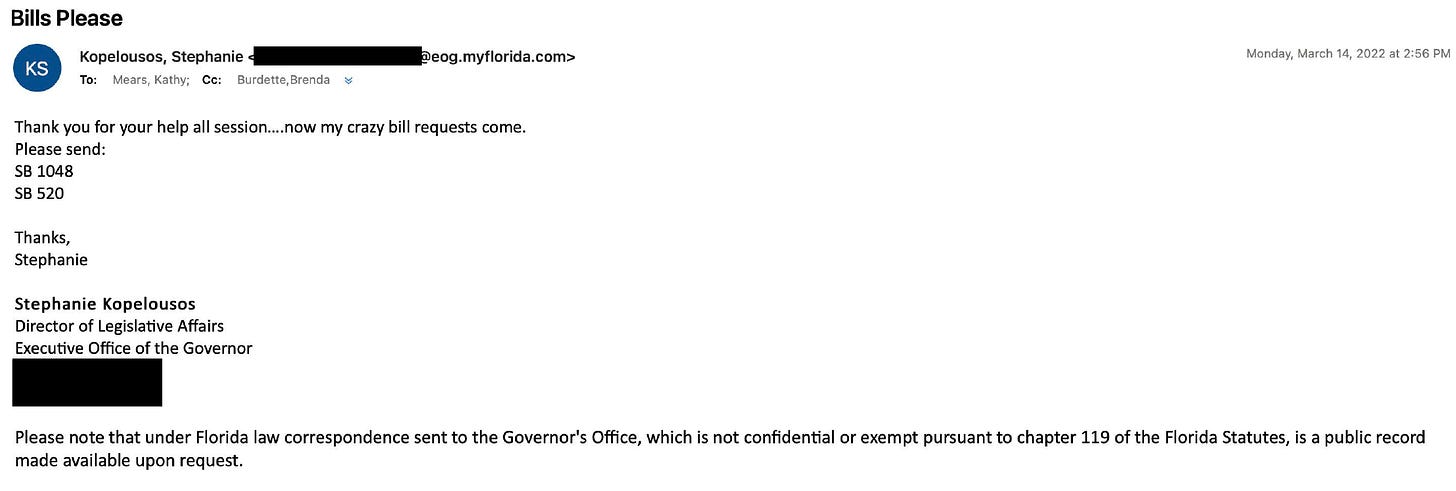

Immediately after the 2022 session ended — only about an hour after DeSantis concluded a post-session press conference in the Capitol rotunda — DeSantis legislative affairs director Stephanie Kopelousos emailed the chief of staff in the Florida Senate and asked to have the presidential bill search sent to the governor.

The governor signed the bill into law the very next day. Kopelousos did not respond to a request for comment.

‘Maximum wiggle room’

Lawmakers involved in the presidential-search legislation all knew that the DeSantis administration was about to fill the top job at the state’s flagship university: The University of Florida.

The bills began moving days after UF’s then-president, Kent Fuchs, announced that he would soon step down. Hosseini, the DeSantis donor and UF board chair who helped push the legislation, appointed the search committee two weeks after DeSantis signed it.

But few, if any, lawmakers knew how the administration would immediately abuse the new law.

The law requires universities to disclose the “final group of applicants.” And Hosseini said publicly that UF’s search committee would “recommend a small number of highly qualified candidates” to the university’s board of trustees.

But UF’s search committee ultimately recommended just one finalist: Sasse, the now-former United States senator from Nebraska. So the Republican politician was ultimately the only applicant that UF’s board of trustees considered for the job — and the public has no way to know whether he was picked over more qualified contenders.

Brandes said UF and the DeSantis administrationmanipulated the search process in a way that lawmakers never intended, although Brandes said he does not believe the Governor’s Office deliberately deceived lawmakers when they advocated for the bill.

“I don’t think they were nefarious in their support,” Brandes said. “I think since it’s passed — as they have with so many other policies — they have tried to find the maximum amount of wiggle room.”

Meetings in the dark

It’s worth remembering how DeSantis and his allies exploited that “wiggle room” as the Legislature considers passing more laws that would weaken oversight of his administration.

The most far-reaching proposal would allow the administration to conceal a vast array of records relating to the governor’s meetings and travel.

The legislation (House Bill 1495 and Senate Bill 1616) would exempt from public disclosure any records held by a law enforcement agency — like the Florida Department of Law Enforcement — that deal with security or transportation for the governor, other top state leaders or their guests.

This is a sweeping bill. It would not only cover security-related records, like threat assessments and operational plans. It would also exempt records like travel information and “personal information unrelated to the official duties of the protected individuals.”

So if DeSantis were to go on a trip that mixes official state business and political campaign work — like, for example, meeting with big donors in between public events — agencies could now conceal records that might reveal details about those donor meetings.

It also extends beyond travel. The legislation, which was broadened during a Senate committee hearing last week, would even let DeSantis refuse to disclose the names of people he meets with at the Governor’s Mansion, if those meetings aren’t related to his official duties as governor.

And this new public-records exemption would be retroactive. So it would allow the DeSantis administration to deny public-records requests that it has been stalling on for months — like a records request that Gannett’s Florida newspapers made more than nine months ago, which the Governor’s Office still hasn’t fulfilled.

That’s not all. The Florida Senate is also moving forward with a last-minute rewrite of the state’s election laws, which, among other things, would force new hurdles on first-time voters, allow local elections offices to disrupt early voting, and throw new obstacles in front of voter-registration groups.

But buried deep inside Senate Bill 7050 — starting on page 92 of a 98-page piece of legislation — are provisions that would allow the governor, other politicians and the political committees that attack opponents on their behalf to operate for longer periods of time without disclosing their donors.

Under reforms enacted a decade ago, DeSantis, lawmakers and political committees must reveal their donors at least once a month — and more frequently in the run-up to an election. But this bill would only require them to disclose donors every three months, except right before an election.

That would make it harder for the public to learn details like which special interests are stuffing cash into lawmaker campaigns right before the start of the 60-day legislative session.

The process aside, it should be noted that Ben Sasse has a Ph.D. in history from Yale, taught at the LBJ School at UT Austin and was president of an (admittedly small) college for four years, in addition to being in the Senate. Compare that with the new "interim" president of New College, a lawyer and politician with no significant experience in education.

Probably all meant to hide what he is really about... extreme power and the complete elimination of Democracy as we know it. If you're willing to participate in force-feeding detainees in Gitmo through their nasal passages (which seems to be a war crime) - I am sure you would be willing to do much worse in the name of power. He's only started his quest for ABSOLUTE power. -------

"Prysner’s interview with Adayfi, titled “Ron DeSantis's Military Secrets: Torture & War Crimes,” aired on Nov. 18, 2022. A short time later, it caught the attention of Joe Kloc, an editor at Harper’s magazine."

https://www.aol.com/news/desantis-not-good-guy-says-005257032.html